The human digestive system is a continuous long muscular tube starting at your mouth and ending at the anus. The system breaks down food by mechanical and chemical means, and then absorbs the nutrients.

The average amount a person eats per day is 1.5 kilograms, which is about 550 kilograms of food a year. That’s more than the weight of two bears!

All of this food we eat goes to the perpetually hungry cells of our body. However, your cells can’t eat a whole salad, so the body must convert it into smaller molecules that the cells can access and use. This is the primary function of our digestive system. Along with the circulatory system, the digestive system is a “meals on wheels” program for the cells of your body.

If it weren’t for digestion, we wouldn’t have the energy to work and play. Not only that, but digestion enables the body to use the nutrients present in food to grow and renew itself.

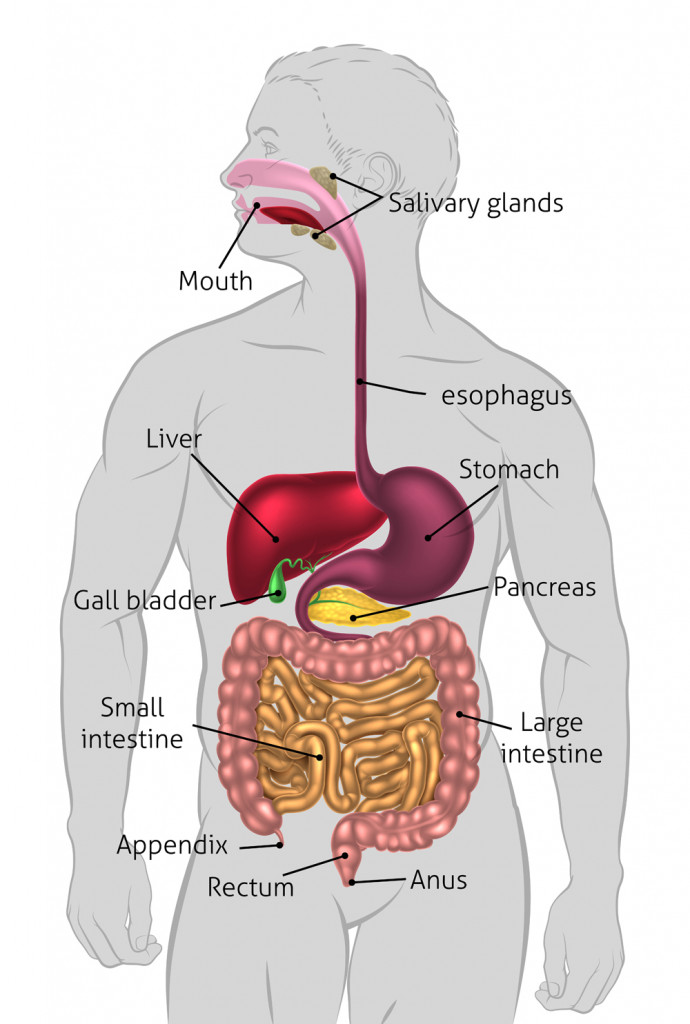

What Is The Digestive System?

The digestive system is like a biological factory that is home to many organs, glands and tissues that manage the task of nourishing us. It deconstructs the food we eat into its basic nutrients–carbohydrates, proteins, fats, and nucleic acids, from molecules like DNA and RNA, that the body can absorb.

There are 7 main organs in the digestive system–the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum and anus. From the mouth to the anus, all these organs are linked together by a twisting and tangled tube composed of soft tissue and muscle. This tube is called the alimentary canal or the gastrointestinal tract (the GI tract for short), but it is most commonly known as the gut.

These 7 organs get some help from 3 additional glands–the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder–each of which contains glands that secrete chemicals and help digestion occur.

Also Read: Does Our Stomach Digest Food On A “First Eat, First Digest” Basis?

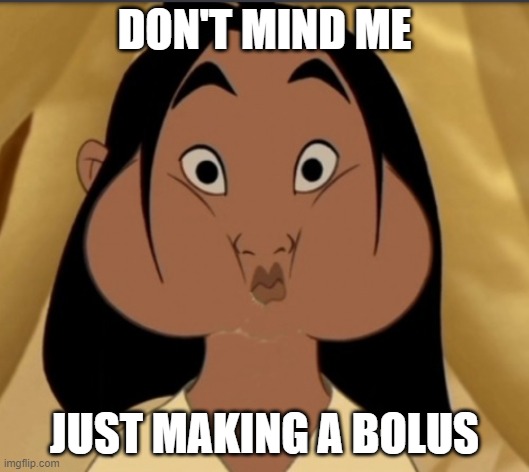

The Mouth – Making A Bolus

The process of digestion begins before you’ve even put the food in your mouth. Upon seeing, smelling or even thinking about lunchtime, your brain will begin preparing your gut for the food. Your mouth will become flooded by saliva in anticipation of the meal, and your stomach will prepare its arsenal of digestive juices.

However, once you take a bite of your food, that’s when the action really begins. The teeth work hard to tear and grind, breaking down food into increasingly smaller pieces.

This is referred to as mechanical digestion—physically crushing food into smaller chunks.

At the same time, salivary glands present in our mouth secrete saliva—a watery liquid containing a host of enzymes. Enzymes are proteins that speed up a given reaction. The saliva contains amylase, which breaks down carbohydrates, as well as lingual lipase, which goes to work on fats.

The combination of chewing and saliva turn the food in our mouths into a pasty ball called the bolus. We swallow the bolus, which travels down our food pipe, or esophagus, to the pouch of acid we know as our stomach.

The esophagus pushes the bolus via involuntary smooth muscle movements. The muscles contract and relax, similar to how a slug or caterpillar moves by contracting its whole body, pushing the bolus down into the stomach. This muscle movement happens throughout the gut and is formally called peristalsis.

This muscle movement ensures that the food only travels to the stomach and not the other way around, which is why even if we’re upside down, our stomach’s contents stay right where they are!

The Stomach – The Gastric Phase Of Digestion

After its journey through the esophagus, the bolus has now reached the stomach.

Remember how we said the alimentary canal is a continuous tube of muscle? Well, here at the stomach, that tube takes the form of a muscle sack. The stomach has several jobs—it takes food from the esophagus, breaks it down with gastric juice (stomach acid + enzymes), and then passes it on to the small intestine. In fact, the stomach makes around 4 liters of gastric juice per day!

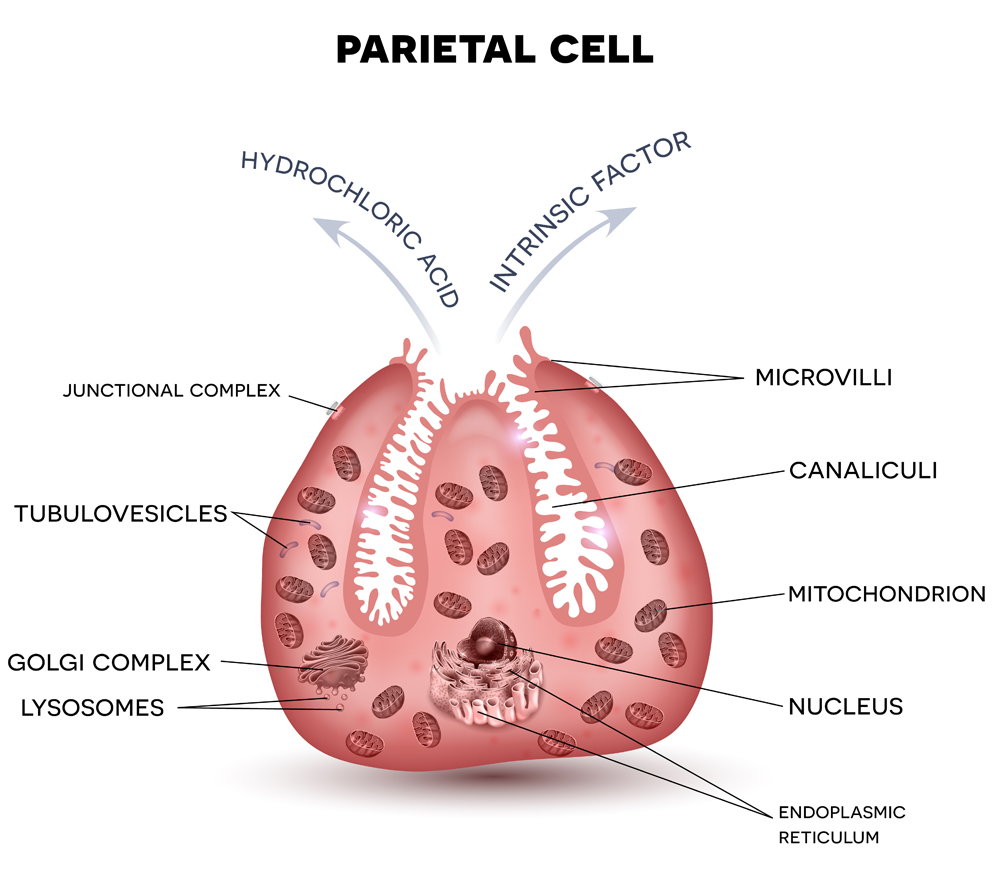

After the bolus enters the stomach, the organ secretes copious amounts of hydrochloric acid, released by parietal cells that line the inner wall of the stomach. This stomach acid is so strong that it can even dissolve metal! Additionally, the stomach produces a thick layer of mucus to protect itself from acid.

The hydrochloric acid chemically burns the food and kills any pathogens that are present.

The low pH from the acid also activates pepsin, an enzyme secreted by the stomach cells. This enzyme helps break down proteins into smaller pieces called peptides. The inactive form of pepsin is pepsinogen. Why does it have an inactive form? So that pepsin doesn’t digest and break down your own body’s proteins in the absence of food.

Along with hydrochloric acid, parietal cells also secrete “intrinsic factor”, which helps cells absorb vitamin B12. Without that, our body wouldn’t be able to make DNA!

The stomach senses the food, and begins tossing the mixture. Peristalsis tosses and squeezes the food even further. The stomach works like a churner, where the food is crushed and mixed with stomach acid, ensuring that everything gets equally digested.

It takes the stomach anywhere from 1 to 4 hours to digest food, after which the bolus that entered the stomach has turned into chyme. The stomach now opens a sphincter valve, called the pyloric valve, and gradually releases the chyme into the small intestine.

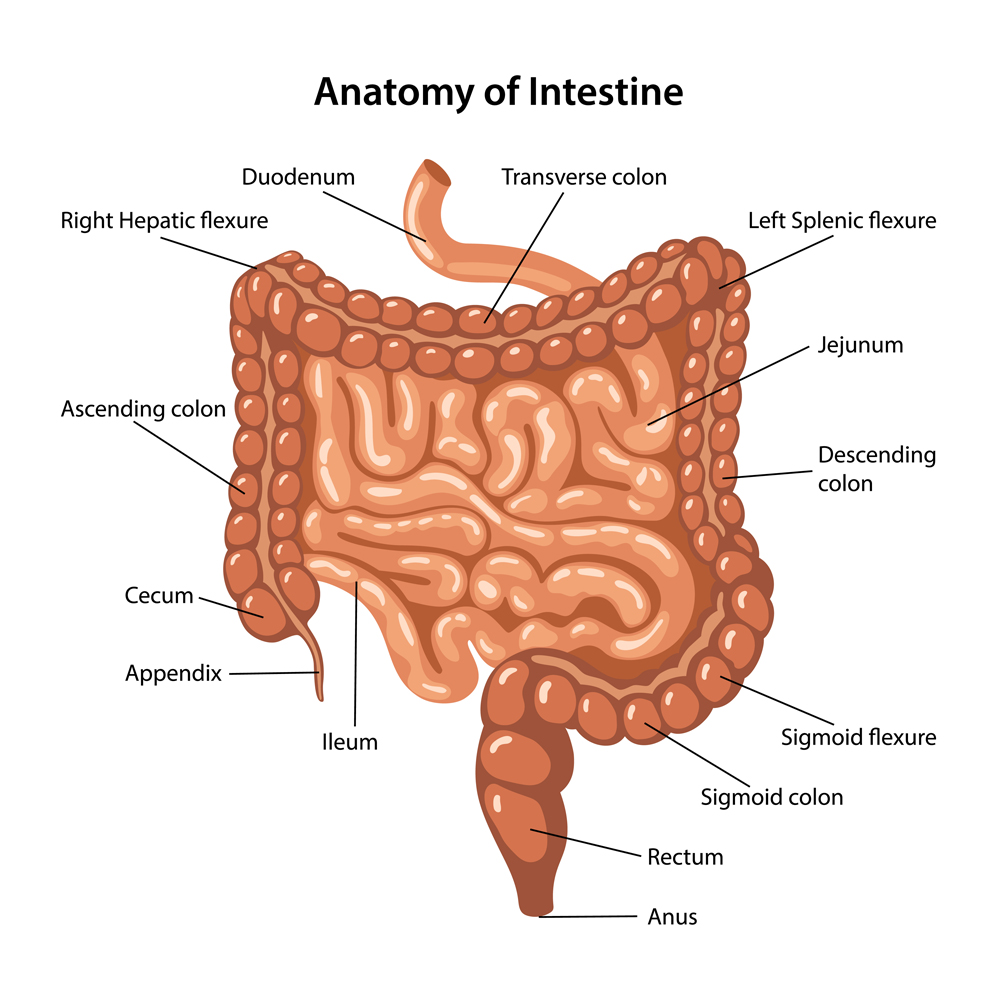

The Small Intestine – The Intestinal Phase Of Digestion

Here, a biological cocktail composed of all our various enzymes, digestive juices and other biomolecules forms and breaks down the food. These even smaller food molecules are absorbed as they move down the small intestine, which stretches for almost 20 feet!

The small intestine has three anatomically different parts–the duodenum, jejunum and ileum.

Once the stomach begins emptying its contents into the duodenum, the duodenum will signal via hormones to stop digesting.

The duodenum will also signal the liver, pancreas and gallbladder to give the food chemicals one final breakdown.

Into the duodenum, via the pancreatic duct, the pancreas secretes digestive enzymes to break down proteins into their smallest unit, amino acids, along with fats.

The gallbladder secretes bile, which is made in the liver. Bile has certain salts that emulsify fat, so it gets dissolved in the watery digestive juices. This makes it easier for the pancreatic enzymes to digest the fat more rapidly.

As peristalsis pushes the chyme further, the small intestine continues to absorb nutrients and water.

For example, the duodenum absorbs most of the iron, the jejunum absorbs the majority of the vitamin folic acid, while the ileum reabsorbs the bile salts.

Lining the inner surface of the intestine are very tiny projections called villi. These are finger-like structures that grow out of the inner lining of the intestine. Think of it as your own hairy carpet, inside your body, that traps all the food traveling along the gut.

The villi increase the surface area of the small intestine, which allows for even more nutrients to be absorbed into the bloodstream.

The Large Intestine – Making Poop

Through a muscular opening called the ileocecal valve, whatever nutrients that couldn’t be absorbed by the small intestine pass into the large intestine.

The large intestine’s job is primarily to absorb water, but it also gets a little help from our microscopic intestinal friends – gut bacteria. Gut bacteria present in the large intestine help break down tough-to-digest food molecules, such as fiber, and synthesize vitamins while doing so!

It takes about 36 hours for food to fully pass through the large intestine.

Finally, after passing through the large intestine, the remaining leftover, indigestible food or waste settles in the rectum.

Once it passes through, the waste (yes, we mean poop) leaves our body from the anus.

Digestion is critical for our body because it breaks down all the complex biomolecules present in our food to the simple materials that our body’s cells are best equipped to work with. As we’ve just learned, this process is done both mechanically and chemically.

Your gut also plays a key role in your mood due to its connection with the nervous system. Believe it or not, gut bacteria help your immune system in ways that we still don’t fully understand!

So, next time you’re tearing through a bag of Doritos, be confident in the fact that your digestive system is already working hard to break down those Cool Ranch chips and pull as much energy out as it can!

Also Read: Ingestion To Excretion: Journey Of Food From The Time It Enters Our Body To The Time It Leaves

How well do you understand the article above!