Table of Contents (click to expand)

It is possible to forget something/someone on purpose. There are various methods that can be used to achieve this, such as getting rid of the context, tweaking the memory, or reprimanding consolidation.

Memories can be traumatizing, like remembering the last time you dropped your Mac and Cheese and wailed all the way home, without its warmth, empty-handed. On a far more serious note, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which is generally observed in war veterans or victims of horrific accidents or crimes, has troubled psychologists for ages now. Psychiatric patients often suppress these memories or indulge in conversational psychotherapy in an attempt to get rid of them.

Freud believed that suppressed thoughts are infectious, or even festering — they’ll eventually gush out in a psychotic breakdown or force its bearers to extend their period of mourning, consequently maintaining the suffering that accompanies it. Yet, no matter how deep you bury it, it often oozes out through their hostile or reticent behavior. The idea presumes that long-term memories are permanent or irremovable.

Does this mean that a tortuous episode will persist forever, tormenting its bearer throughout his or her entire existence? A new study suggests otherwise…

How Does Memory Work?

Human memory is exceptionally complex and scientists still haven’t fully wrapped their heads around it. Currently, neurologists believe that memories reside in neuronal pathways that then flow through and connect several units that are essential to our intricate mental workings.

The strength by which neurons in a pathway are connected by their dendrites determines whether a given memory is short lived or imprinted forever.

Habitual memories, such as the knowledge of how to drive a car or tie your shoelaces, are distributed throughout the brain. Emotionally intense memories, such as love, heartbreak or fear, are stored in the amygdala. Finally, the consciously evoked memories of dates for appointments or the names of actors are stored in the hippocampus.

The most palpable or identifiable analogy is that of a computer, which stores information in a separate unit, such as a hard drive. However, this analogy must be immediately refuted. Digital memories are mere recordings, and evoking them represents an act of reproduction, whereas a human brain reconstructs them.

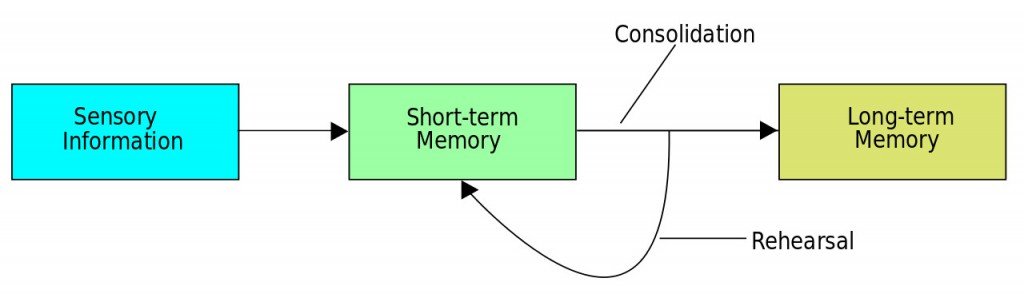

When we learn something new, chemicals in the brain strengthen the synapses that connect neurons to form short-term memories. Furthermore, these can be transitioned to permanence by recurrent mental rehearsing and recreation of the event. Every time you reflect on a past event, you practically relive it in your head, and each time you relive it, you strengthen its corresponding network. Therefore, long-term memories are just more powerful connections. This process of cementing a fresh event after it is mentally registered is known as consolidation.

Following that analogy, the cement does take some time to dry. No one will deny that freshly registered information is highly susceptible to slip away if it isn’t fully established due to lack of attention. The amount of time consolidation might take is different for every individual and, depending on the amount of information being stored, it might take hours or even days to consolidate an episode. That being said, one thing is certain — the brain can only achieve prolonged persistence by repeatedly retracing an event, consequently strengthening its associated pathway.

One more peculiar finding is the importance of context in retrieving memories. Neurologists have found that memories become excruciatingly difficult to retrieve when retrieval is attempted without context. This makes more sense when you consider mnemonic tricks, such as the very popular “memory palace”, where objects to be remembered occupy mental spaces throughout a mental palace.

Recalling an old memory isn’t solely restricted to the mental imagery or gist of an event, but also the context in which it occurred. The brain, along with the gist, reconstructs the entire scene in all its details, replete with the smell of the coffee you drank, the somber color of the wall behind, or the song playing in the background. These contextual triggers can act as cues to invoke a memory or – in a Pavlonian way – a certain behavior.

This is usually common in drug use, where addicts tend to associate certain places with their intoxication. A shady park or the sight of a lighter might be unconsciously recognized as a cue that can spark a craving, forcing him or her to seek the drug.

Now that we know how we make a memory, we can discuss the possibility of unmaking one.

Also Read: Why Do Some People Have A Better Memory Than Others?

How To Forget?

Once a memory is cemented, are we plagued by its persistence forever?

As it turns out, we’re not! If memories reside in neural pathways, they automatically become ingrained in the brain’s plastic structure. This plasticity renders memories malleable — memories might not be completely erasable, but they can certainly be trifled with.

Get Rid Of The Context

One method is consciously forgetting the context in which a traumatic memory occurred. The surfacing of a memory to our consciousness in the presence of a contextual cue is evident in songs that remind you of your first love, or the tragic heartbreak that followed. Purposely forgetting a particular song or movie that you watched together will aid in eventually getting rid of the infatuation and the memories it brings up. If the pathways associated with these contexts go unnoticed, the memories they give form to will eventually fade away as well.

Tweaking

Also, the contents of memories can be substituted or tweaked… with deliberate effort. Purposely thinking about green will eventually push out your previous thought – let’s say “red” – from your mind’s eye. This sort of swapping can be taken a step further by replacing the color green with absolutely nothing.

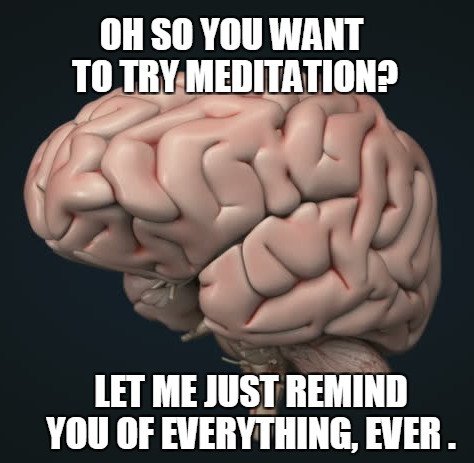

This is evident in mindful meditation, where the purposeful dismissal of every thought that crosses your mind is promoted. This is certainly strenuous, to the extent of being next to impossible for some, but it is still doable.

Reprimanding Consolidation

The last technique I’m going to mention is the most exciting one. Daniela Schiller, a leading neurologist and investigator of the relationship between memory and fear, explains, “We need fear memories to survive, how else would you know not to touch the burner again?” According to her, forgetting a memory’s context might not be a permanent fix — however wane, the memory still persists in some remote cabinet of our brain.

Daniela and her team are interested in separating or subtracting the fear associated with a traumatic memory. According to her, the emotion that accompanies a memory, such as fear, anxiety or stress, can be shrugged off when the memory begins to consolidate.

(Fun Fact: Daniela Schiller is an ardent drummer and a part of a band formed with her colleagues. The band is named Amygdaloids.)

As mentioned earlier, each each time you remember something, you relive the episode in your head. However, fMRI scans have shown that not only do we live it repeatedly, but also consolidate it each and every time! This is known as re-consolidation. Re-consolidation is what strengthens a memory’s corresponding pathway. Daniela’s solution is to hinder this process by assailing the pathways with suitable biochemical drugs.

This was successfully tested on rats by implanting a correlation between a shining light and an electric shock in their brains by providing them with a shock every time the light blazed. The scientists then waited 2-3 days to let consolidation cement this correlation. The rats were then disposed to the bright light again. Naturally, they ducked in panic, which was evident in their elevated heart rate and antsy eyes.

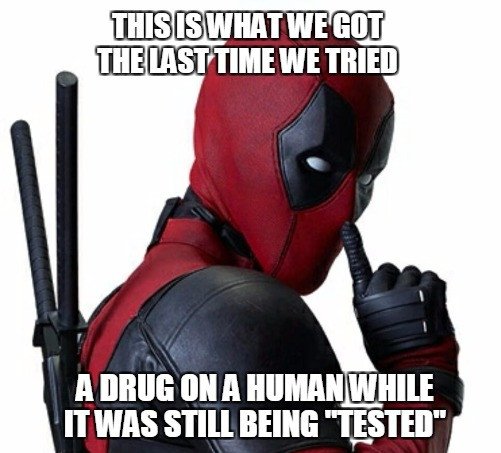

To test their hypothesis, the scientists exploited this window of opportunity and injected a suitable drug that partially blocked the flow of neurotransmitters – the messengers of neuronal information – between neurons, thereby denying any re-consolidation.

The tests were conducted on two sets of traumatized rats, where one group was given the actual drug and the other a mere placebo. The results showed that the next time a light was shone on the rats, the latter continued to show signs of agony, whereas the first group were indifferent to it, as though nothing had happened!

However, these results are highly dangerous to replicate on humans, and it would be irresponsible to claim that the results would be the same. The biochemical drugs are still in the testing phase, but this solution seems to be the most effective and, most importantly, the quickest.

Tampering with a memory or getting rid of it entirely may initially seem unethical. However, its consequence, similar to a well-intended lie — a good cause — spares us the interminable analysis that accompanies this compelling moral dilemma. The intention to help bring people peace is the foremost and primary objective.

Also Read: How Are Memories Stored And Retrieved?

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Manning, J. R., Hulbert, J. C., Williams, J., Piloto, L., Sahakyan, L., & Norman, K. A. (2016, May 5). A neural signature of contextually mediated intentional forgetting. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Schiller, D., Kanen, J. W., LeDoux, J. E., Monfils, M.-H., & Phelps, E. A. (2013, November 25). Extinction during reconsolidation of threat memory diminishes prefrontal cortex involvement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- (2015) Memory Consolidation. The University of California, San Diego

- Memory consolidation | LaLumiere Lab | Psychological and Brain .... The University of Iowa

- Neuroscientists identify brain circuit necessary for memory .... news.mit.edu