Chimeras are organisms with two or more genetically different patterns from other organisms within themselves. Human chimeras may be temporary or permanent.

When you search the word “chimera” on the internet, the first result you get is a Merriam-Webster dictionary explaining that: “In Greek mythology, the Chimera was a fearsome, fire-breathing monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a dragon’s tail. She terrorized the people of Lycia until their king, Iobates, asked the hero Bellerophon to slay her.”

Well, human chimeras aren’t quite that scary, but the idea is similar.

What Is A Human Chimera?

Each organism has its own separate DNA, which codes for it and only it. Chimeras, however, are organisms that have two or more genetically different patterns from other organisms contained within themselves. A human chimera is a person containing cells that have a different genetic makeup.

Hollywood TV shows have a few examples of chimerism. On Grey’s Anatomy, an adolescent is found to be a hermaphrodite and a chimera when a tumor she harbors happens to be the testes of a vanished twin. In House, doctors take up the case of a boy formed through in vitro fertilization. Conflicting medical tests and the discovery of cells with a different type of DNA reveal the problem: he is a chimera.

In real life, the first human chimera was reported in 1953. For the record, human chimeras are not artificially generated through some futuristic genetic manipulation experiment. In fact, the condition may be more common than we expect; many cases may never even be detected.

Another thing to note is that chimeras—human or otherwise—are not necessarily produced through sexual reproduction.

A zygote is formed due to the fusion of two gametes from parents of the same species. A hybrid is formed due to the fusion of gametes from two parents who do NOT belong to the same species. However, a chimera does not need to come from a direct fusion of two gametes belonging to the same parents.

For example, mules born from a male donkey and a female horse are hybrids, not chimeras, but in the case of a chimera, the DNA is not from the parents… it is from an entirely different organism (barring, of course, natural twins).

Also Read: What Is A Zygote? How Is It Different From An Embryo?

Temporary Chimeras

Temporary chimeras are human individuals that harbor some other organism’s DNA temporarily.

One common instance of this is a blood transfusion.

When the blood from another individual is transfused, the body of the patient subsequently contains two types of cells. One type is its own cells and the other is that of the donor. Since all blood cells have a limited lifespan, these ‘foreign’ blood cells eventually die, and are once again replaced by the individual’s own cells.

Another instance of chimerism occurs during pregnancy.

Sometimes, a few cells of the fetus may pass into the mother’s body through the placenta or during the birth of the child. These fetal cells may remain in the mother’s body only temporarily. In a few cases, the fetal cells remain within the mother for longer periods, which we’ll discuss later in this article.

Also Read: Virgin Birth: Is That Even Possible?

Examples Of Permanent Chimerism

During Bone Marrow Transplants

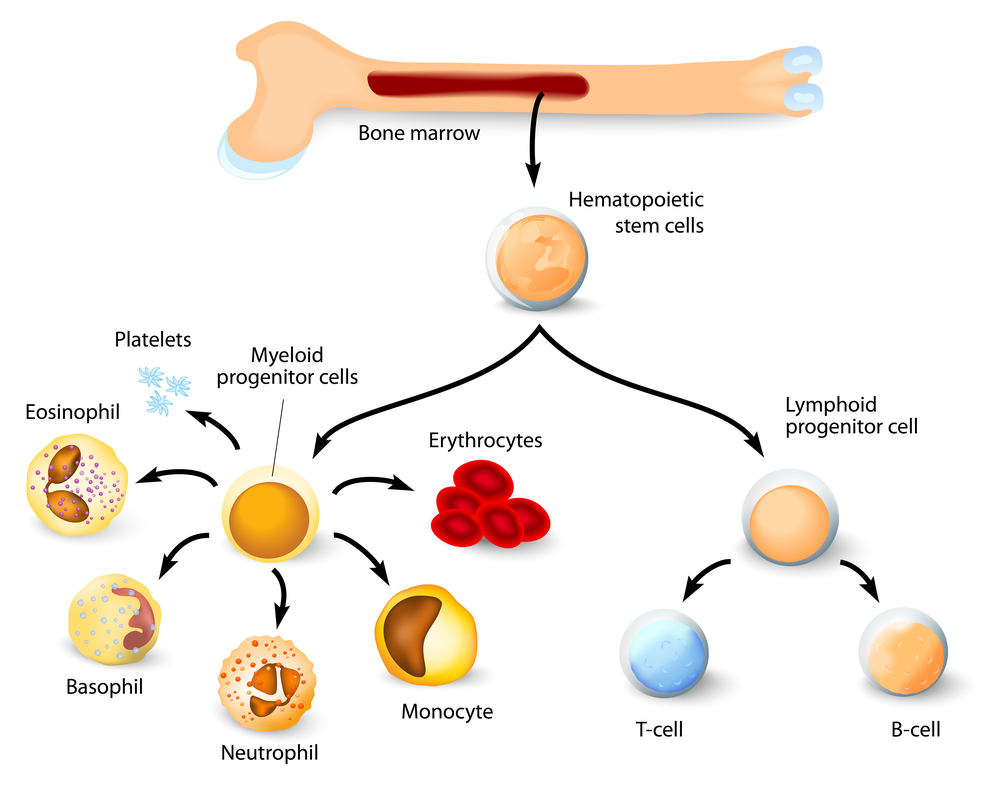

Bone marrow is the region of our long bones that is responsible for producing blood cells, such as red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

In medical conditions such as leukemia, the bone marrow is diseased and is unable to perform its functions. In such cases, the ultimate strategy is to replace the defective bone marrow by transplanting bone marrow cells from a donor.

If all the cells of the bone marrow are completely replaced, the future cells would be from the donor’s bone marrow, making the recipient a 100% chimera. This is called complete chimerism. Throughout their life, the recipient would harbor two types of cells: one, their own and the other, from the donor, running in their veins and arteries. If, however, only a part of the bone marrow must be replaced, the patient would become a partial chimera.

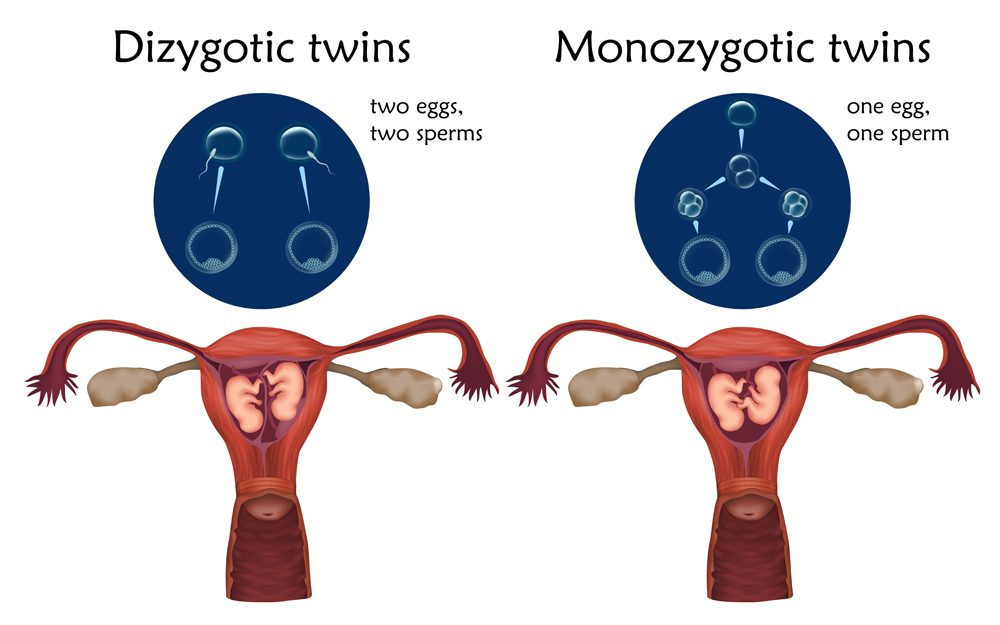

During Twin Absorption

Fraternal (dizygotic) twins are the twins generated from two zygotes. Two zygotes can be formed from two ova being simultaneously released and fertilized by two sperm cells. On the other hand, identical twins (monozygotic) are twins generated when one zygote divides into two (or three) before implantation in the uterus.

Quite often, one of the fraternal twins dies inside the mother’s womb. The portion of this twin that was already formed is absorbed by the other remaining twin. The individual, when born, is a human chimera, as it has the DNA of two organisms inside it.

More often than not, this does not create any problems, and the individual continues to live a normal life.

In some cases, such as when the sex of twins was different, complications may arise. If the surviving female still has cells containing the Y chromosome (found only in men) in her body, it could lead to the development of certain masculine characteristics, such as rudimentary testes.

During Normal Pregnancy

Cells from a fetus can cross the placenta to reach the mother’s body, and there have been instances where such cells have been found long after the pregnancy ended. This is called microchimerism and is found to make some women permanent chimeras. Cell transfer takes place both ways and can also cause chimerism in the child. The presence of fetal cells has been associated with both positive and negative effects on maternal health.

In a 2012 study, researchers analyzed the brains of a few women from ages 32 to 101 who had died. Strikingly, they found that 63% of these women had traces of male DNA (Y-Chromosome) in their brains. This happened because male fetal cells had traveled from the uterus into the mother’s body. The oldest woman to have fetal cells in her brain was 94 years old, suggesting that these cells can sometimes stay in one’s body for a lifetime.

In-vitro Fertilization And Chimerism

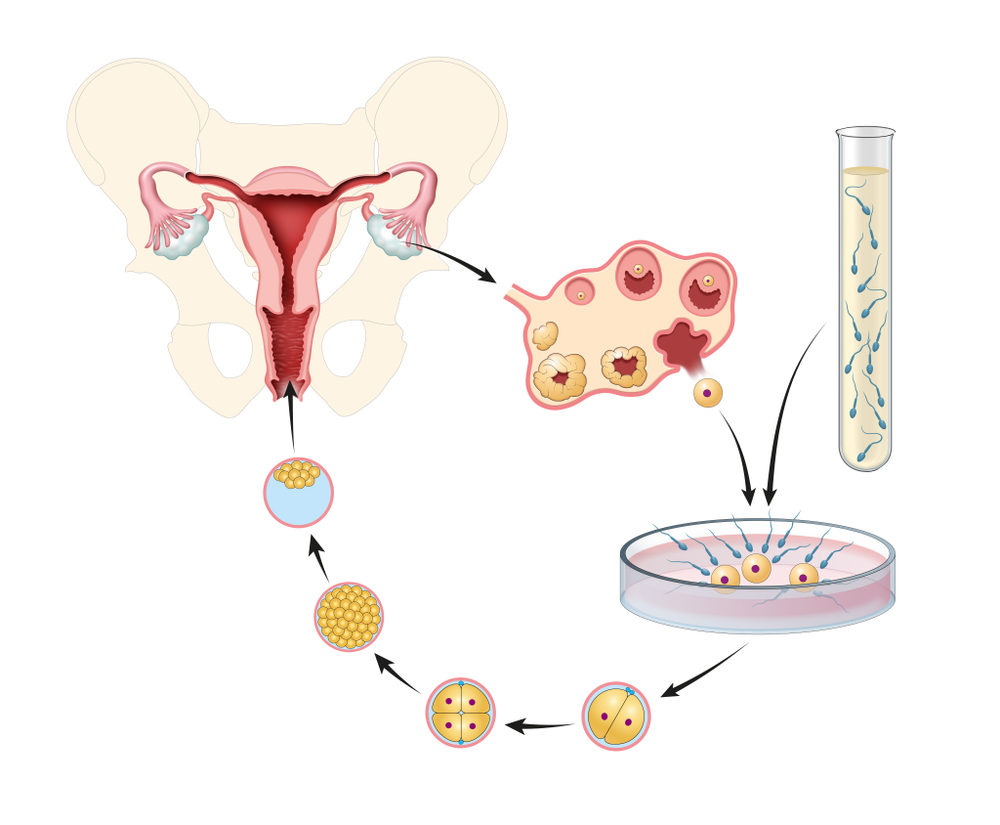

In-vitro fertilization is when fertilization is artificially induced. Sperm are made to fertilize the ovum in a Petri dish, the resulting zygote develops to form an 8-16 celled embryo and is then transferred into the mother’s womb for further development.

Studies have found that in vitro fertilization can actually increase the frequency of chimerism.

There is an increased frequency of twins being formed via any in-vitro fertilization. In most cases, these spontaneous human chimeras are dizygotic twins whose bodies have integrated cells of both genotypes. Charles Boklage, a developmental biologist at the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, who has studied chimerism for more than 25 years, says that about one in eight people is a twin who was born single.

Case Study 1 Of Chimerism

In 2002, a woman named Karen Keegan needed a kidney transplant. She, along with her family members, underwent genetic testing to see if someone could donate her the kidney. The genetic tests revealed that she could not have been the mother of two of her sons. This curious case was later solved by the doctors when they realized that Karen was a chimera! Karen had two genetically different types of cells: one type present in her ovaries and another type found in her blood.

Case Study 2 Of Chimerism

More recently, the American singer Taylor Muhl found a satisfactory explanation to her torso containing two skin tones. As it turns out, she’s a chimera. She’s carrying the genetic material of her fraternal twin sister, whose egg had fused with hers in their mother’s womb. Before this discovery, the doctors explained it as nothing more than an unusually large birthmark!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- 3 Human Chimeras That Already Exist - Scientific American. Scientific American

- Madan, K. (2020, September). Natural human chimeras: A review. European Journal of Medical Genetics. Elsevier BV.

- Wolinsky, H. (2007, February 16). A mythical beast. EMBO reports. EMBO.

- Peters, T. (2007, June 14). A theological argument for chimeras. Nature Reports Stem Cells. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Yu, N., Kruskall, M. S., Yunis, J. J., Knoll, J. H. M., Uhl, L., Alosco, S., … Yunis, E. J. (2002, May 16). Disputed Maternity Leading to Identification of Tetragametic Chimerism. New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society.

- Madan, K. (2020, September). Natural human chimeras: A review. European Journal of Medical Genetics. Elsevier BV.