Table of Contents (click to expand)

Butterflies taste their food through their legs, which have chemoreceptors attached to neurons that can detect the molecules that are edible and those that are not.

When you eat your food, depending on how it tastes, you can quickly decide whether you like it or not. You can thank the taste buds on your tongue for that important aspect of enjoying life (and discerning displeasure)!

Butterflies, however, don’t have taste buds like us mammals. Their mouthparts mainly serve as a straw through which they suck up their food—no chewing necessary. Without so-called “taste buds”, how do butterflies know what is nectar and what isn’t?

Butterflies do taste their food, but not through their mouthparts. Instead, they do it through their feet! Having an animal’s feet serve as taste organs sounds preposterous, which is probably why researchers never even considered the possibility.

Most early research in the field looked at the antenna or the palpi, part of the butterfly mouthparts, as the primary taste organs. The thinking was that if humans and most other mammals had a tongue for taste, a similar organ must serve the same function in insects.

Nature rarely works in such a straight and predictable manner. It was only in the late 1800s that researchers began to take a more out-of-the-box approach to the problem. This is when they discovered that it was the legs, not the mouthparts, that functioned as taste receptors in butterflies!

Taste Buds On Their Legs

Insects are a varied bunch of organisms, making it difficult to generalize a feature across them all. Butterflies have mouthparts designed like straws, so they don’t really have a tongue. Such insects whose mouthparts are only designed to suck liquids are called haustellate insects.

Lepidoptera, the order to which butterflies and moths belong, and Diptera, the order to which flies belong, are both “leg tasters”. The taste buds are called contact chemoreceptors, taste receptors, or basiconic sensilla in some literature.

These chemoreceptors are attached to nerve endings. When chemicals present in the insect’s surrounding come in contact with the chemoreceptors, they activate the nerves, which relay the information to the insect’s brain.

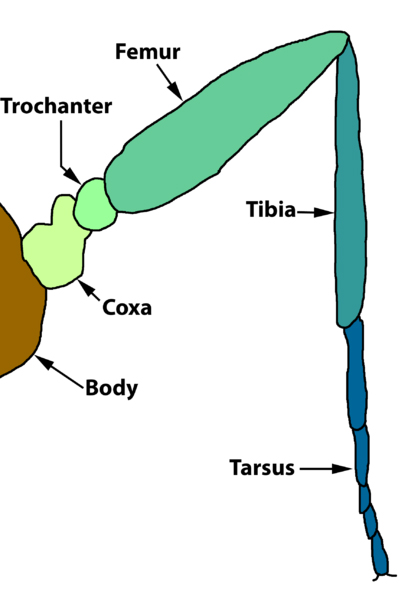

In butterflies, these chemoreceptors lie on the tarsus. Insect legs are subdivided into different segments, as the picture below shows. The tarsus is located distally, meaning “away from the body”.

Just as humans can taste the sweet in sugar and the bitterness of medicine, insects can sense different tastes too! They can sense sweet, bitter, sour and salty through their chemoreceptors.

This strategy is crucial for butterfly survival. In a review published in Insect Molecular Biology, the authors noted that multiple behavioral studies have shown that butterflies use taste to make many important choices. This informs not only what in their surroundings is food, but also guides them in choosing a mate, and deciding where to lay their eggs.

Also Read: How Do We Taste Things?

How Do They Eat?

Now that we know how butterflies taste their food, the natural question is… how do they eat it? As mentioned before, butterflies have haustellate mouthparts. They can’t actually chew or bite their food, so they just drink liquids in the form of nectar, sap, juices from fruits, and certain minerals.

Haustellate mouthparts are an adaptation from the mouthparts used for chewing, called Mandibulate mouthparts. All “primitive” insects had mandibulate mouthparts, because they had large mandibles to crush their food. As insects evolved, they developed different mouthparts to adapt to their environment and dietary needs.

Butterflies have a long straw-like structure called a proboscis that performs these important tasks. Initially, when butterflies come out of their pupal case or chrysalis, the proboscis is separated into two parts.

The first thing the newly emerged adult must do is assemble its proboscis using palpi located near the proboscis to form one long, tubular structure. If it doesn’t achieve this in a timely manner, the butterfly can’t drink and won’t be able to survive for very long.

New butterflies often curl and uncurl their proboscis to test it. When the proboscis is not being used, it remains curled up, like a garden hose.

Butterflies mostly eat nectar or the pollen of flowers. They perch on the flower, unfurl their proboscis and suck at the tasty juice, but that’s not the only thing they eat.

Butterflies show a peculiar affinity for mud. This behavior, called puddling or mud-puddling is mostly seen in male butterflies, mainly in tropical regions, though it also occurs in more temperate climes. Male butterflies congregate at puddles because it’s a great source of minerals that are essential for healthy sperm. These nutrients are transferred to females during mating and helps to improve the viability of her eggs.

One particularly valuable mineral is sodium. Since plant nectar is deficient in sodium, many insects on a plant diet are frequently sodium starved. This is why many butterflies are attracted to sweat, dung or even carrion. Additionally, any water bodies near puddles might allow butterflies to cool off during hot and dry weather.

If you’re sitting in a park or garden on a sunny day, and a butterfly happens to land on you, many will take it as a compliment and a sweet little blessing, but in truth, the butterfly is probably just attracted to the salt and sweat on your skin!

Also Read: Moth Food: What Do Moths Eat?

Do you remember how butterflies eat?

References (click to expand)

- Agnihotri, A. R., Roy, A. A., & Joshi, R. S. (2016, May 26). Gustatory receptors in Lepidoptera: chemosensation and beyond. Insect Molecular Biology. Wiley.

- Frings, H., & Frings, M. (1949, May). The Loci of Contact Chemoreceptors in Insects. A Review with New Evidence. American Midland Naturalist. JSTOR.

- Mouthparts | ENT 425 – General Entomology. North Carolina State University

- Beck, J., Mühlenberg, E., & Fiedler, K. (1999, April 14). Mud-puddling behavior in tropical butterflies: in search of proteins or minerals?. Oecologia. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.