Table of Contents (click to expand)

Should you save a seat at your Christmas table for viruses? A 2021 study explored the origins of life and found that viruses could predate cells, or may have even detached from an existing cell that eventually evolved into you and me.

Ah, viruses! Tiny things that are barely alive, yet capable of wreaking havoc on all kinds of life. Anything that has a metabolism, from bacteria to plants and animals, will find these beautifully merciless little organisms leeching on them. But how can a 20 nm (~0.0000008 of an inch) thing be related to you and me? All organisms have ways to pass down their genes to their progeny independently, without having to first hijack a different organism and coerce it into making genes for it, but not not the virus.

How can they be our cousins? Are we doomed to truly call these terrifying creatures family?

A 2021 study by Hugh Harris and Collin Hill from University Cork College, Ireland, posits a few interesting possibilities on how viruses could actually be related to us.

How Do We Check The Relationship Between Living Things?

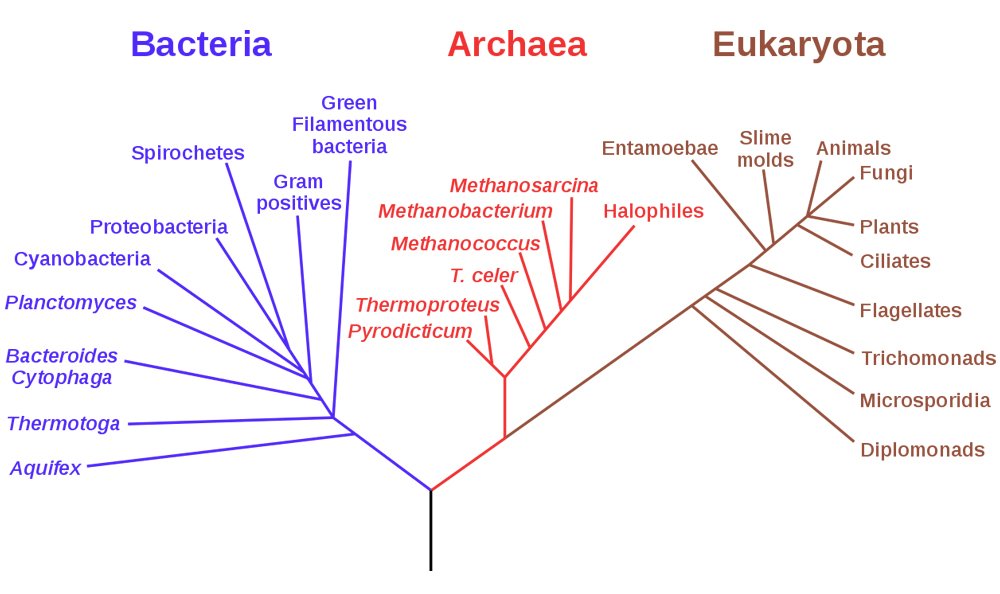

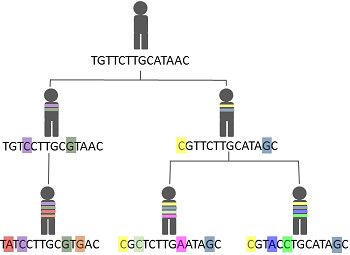

Usually, molecular biologists use something called the molecular clock theory to determine the relationship of all organisms. Simply put, this theory compares the genetic sequences between two organisms and estimates how similar those sequences are.

This is possible because we all share some genes. The ribosomal gene, for example—a common gene whose genetic sequence you can use to figure out if two organisms are genetically closer (similar genetic sequences) or more genetically distant (not so similar sequences)—is typically used, as it’s present in EVERY organism… except in a virus.

Viruses mutate at such a rapid rate that it is futile to even determine the relationship of one viral species with another. The molecular clock method, therefore, can’t be used.

Thus, it seems like there’s no way to determine our relationship with viruses.

However, there might be other ways to determine if they are. The 2021 paper, an exhaustive review paper on viruses and their place on the Tree of Life, by Hugh Harris and Collin Hill, presents such hypotheses. We might not be able to directly measure the relatedness of viruses to other organisms, but there are indirect ways that require some brilliant guesswork (based on some evidence) on how life began on earth.

Also Read: Where Did Viruses Come From?

Could Viruses Be Our (Really) Old Cousins?

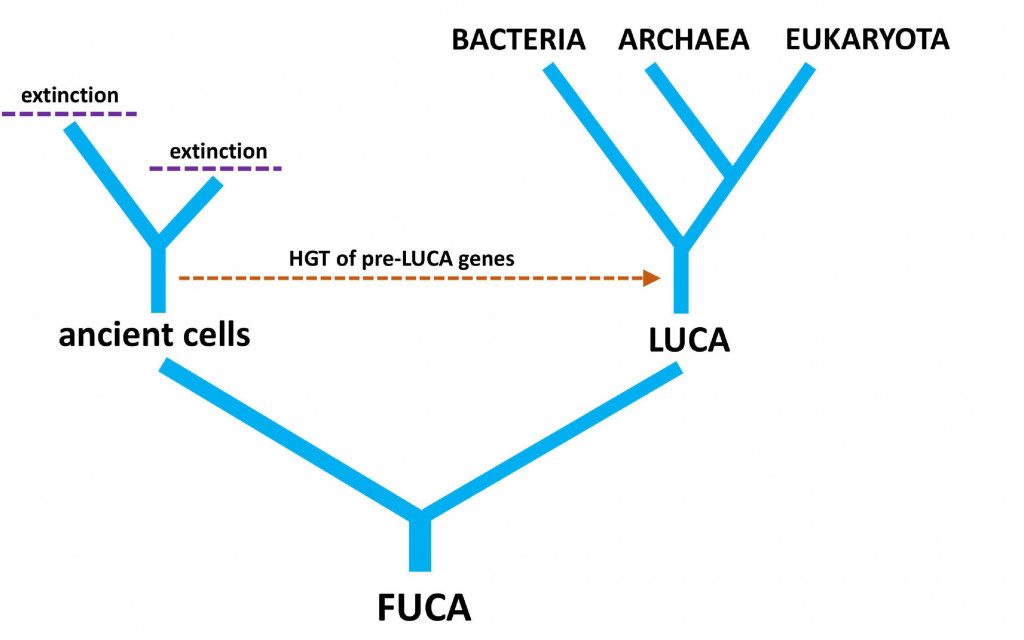

To truly understand the paper’s explanation of the ways in which viruses might have originated, it’s important to know more about LUCA and FUCA.

LUCA is the Last Universal Common Ancestor or the Last Universal Cellular Ancestor. This distinction is important, the study points out, when you’re trying to include viruses into the Tree of Life.

In the study, LUCA is used to talk about the last common ancestor of modern cells. This will exclude viruses. FUCA will be used instead to mean First Universal Common Ancestor—the ancestor of LUCA and other lineages that might have gone extinct, which could be clues to the origin of viruses.

There are many possibilities for the origin of viruses, and the study highlights three major ones that cover the most ground: (1) Viruses-first hypothesis; (2) reduction hypothesis; and (3) Independent evolution hypothesis.

Also Read: Do Viruses Do Anything Outside Of The Body?

Viruses: A Lineage Older Than Life Itself?

We’ll begin with the viruses-first hypothesis.

The authors try to hide their excitement, but it seeps through in their review. The viruses might have existed as “pre-cells”, a kind of organism that can self-replicate, but isn’t part of a cell. And it is NOT parasitic; it was a self-sustaining non-cell-like thing! Yes, this is a fascinating hypothesis, but there is little evidence to back it up.

However, if it were true, given that viruses aren’t really considered living things, it would mean that viruses appeared at the very beginning—a short time after the earth was born 4 billion years ago.

Once Living, But Living No Longer: Did Viruses Ever Live?

The reduction hypothesis.

The next, more plausible theory, is that viruses evolved from cellular ancestors, which is to say that they were once “living” (based on how we define life).

Here, we assume that viruses originated before LUCA, but after FUCA.

In this scenario, early viral cells were parasitic organisms that eventually lost their independence by losing essential self-sustaining genes and became like the viruses we know today.

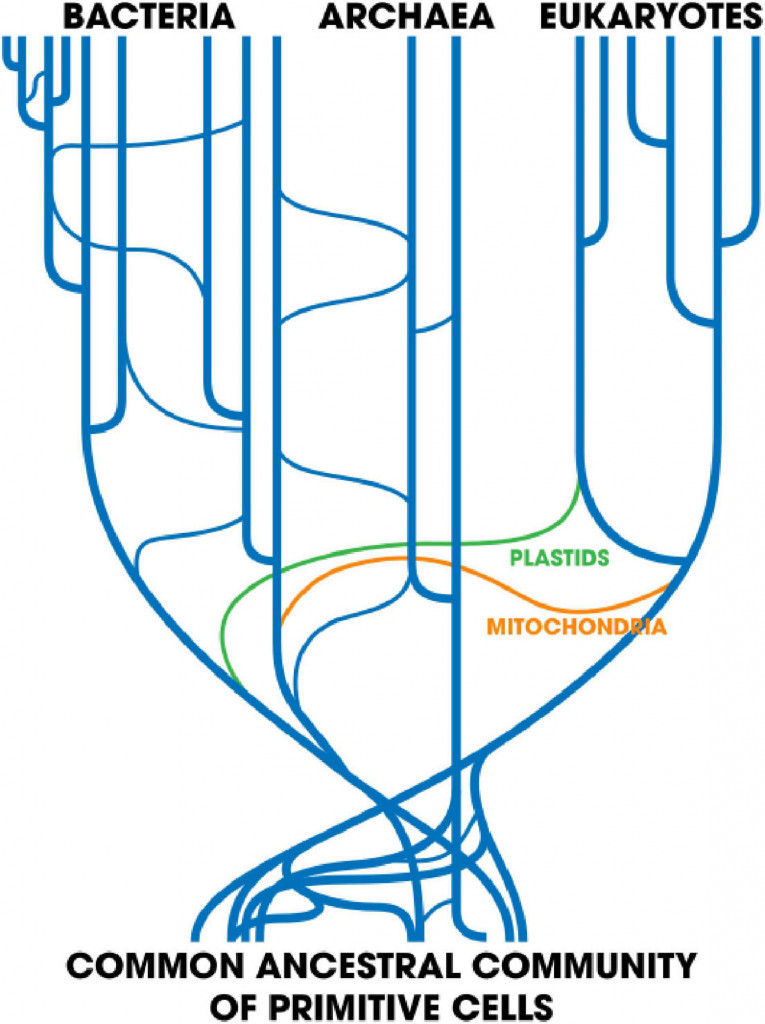

A similar loss of independence has already happened! The mitochondria present in all eukaryotic cells (including us) were initially endosymbiotic bacteria who lost their independence. However, there’s no way to confirm this hypothesis… yet. And finally…

They Come Again And Again: How Viruses Could Have Evolved Multiple Times

The independent-evolution theory.

Also considered the “escape theory”, this is the most interesting of all (and also the most likely, according to some scientists).

Viruses might have independently evolved at least three times in the three different domains of life. Once in Eukaryota, once in Archaea (the old “primitive” cells), and once in bacteria. This theory is mind-bending, as it suggests (with strong reasoning to back it up) that there’s a tendency for the genomes of cells to turn some of their genes and machinery into viruses! These viruses would have once been part of a normal genome, but “escaped” and became parasitic!

Conclusion

Whatever our confusion may be about viruses and their place on the ultimate tree of life, surely they are related to us in some way, which might depend on how we, firstly, define “life” and then how we define “family”. Multiple origins or not, if viruses are truly part of the tree of life, that would mean that all life on Earth as we see it had an ancient mother that lived when our planet had only just begun. These tiny monsters—maybe our distant cousins—could reveal more about how life generally evolves, and not just on Earth!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Lee, M. S. Y., & Ho, S. Y. W. (2016, May). Molecular clocks. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- Horie, M., Honda, T., Suzuki, Y., Kobayashi, Y., Daito, T., Oshida, T., … Tomonaga, K. (2010, January). Endogenous non-retroviral RNA virus elements in mammalian genomes. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium, Lander, E. S., Linton, L. M., Birren, B., Nusbaum, C., Zody, M. C., … The Wellcome Trust:. (2001, February 15). Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Hayward, A. (2017, August). Origin of the retroviruses: when, where, and how?. Current Opinion in Virology. Elsevier BV.

- Harris, H. M. B., & Hill, C. (2021, January 14). A Place for Viruses on the Tree of Life. Frontiers in Microbiology. Frontiers Media SA.