Prince Rupert’s drops are strong bulbous globules made of molten glass with a very fragile tail. While the bulbous head can withstand bullets, the tail breaks under even the slightest force, causing the whole drop to shatter.

Glass is one of the most interesting materials ever discovered and engineered by mankind. While having a specific molecular structure, it has no chemical formula that identifies it amongst other chemicals.

The molecular structure of glass can be altered to cater to various needs, ranging from decorative purposes to bullet proofing. Yet, this mystic material continues to surprise us.

For example, bullet proofing is one thing, but shattering a bullet is quite another. Yes, you read that right. Glass can indeed shatter bullets. As tempted as we are to check this fact for ourselves immediately, let’s take a minute to learn a bit more.

What Kind Of Glass Can Shatter Bullets?

When small bits of molten glass are dropped into cold water, they form shapes akin to a tear drop with a small curly tail. Their shape and some history with an Anglo-German royal led them to be called Prince Rupert’s drops. They are also called by other names, such as Dutch and Batavian tears.

In various experiments conducted by scientists and enthusiasts alike, bullets were found to ricochet off the drop’s head. In this process, very little damage would be incurred by the bulbous head itself, whereas the bullet would disintegrate.

Also Read: Bullet-Resistant Glass: How Does It Work?

What Makes Prince Rupert’s Drops So Special?

If a teardrop-shaped piece of glass shattering bullets isn’t intriguing enough, here’s a fun little fact. If you were to clip the tail of a Prince Rupert’s drop, the whole thing shatters explosively into tiny fragments.

Herein lies the conundrum… How can something capable of shattering bullets break by merely snipping its thin tail? The secret lies in the drop’s structure and its process of formation.

How Are Prince Rupert’s Drops Formed?

When molten glass droplets are dropped into cold water, the glass undergoes a process of quenching. If you are familiar with the word, chances are that you have heard of quenching in metals.

Quenching refers to a process of the sudden cooling of materials that have been heated up to their molten state. This is achieved by immersing the molten material in various media, such as cold water and oils.

What Happens During The Quenching Of Glass?

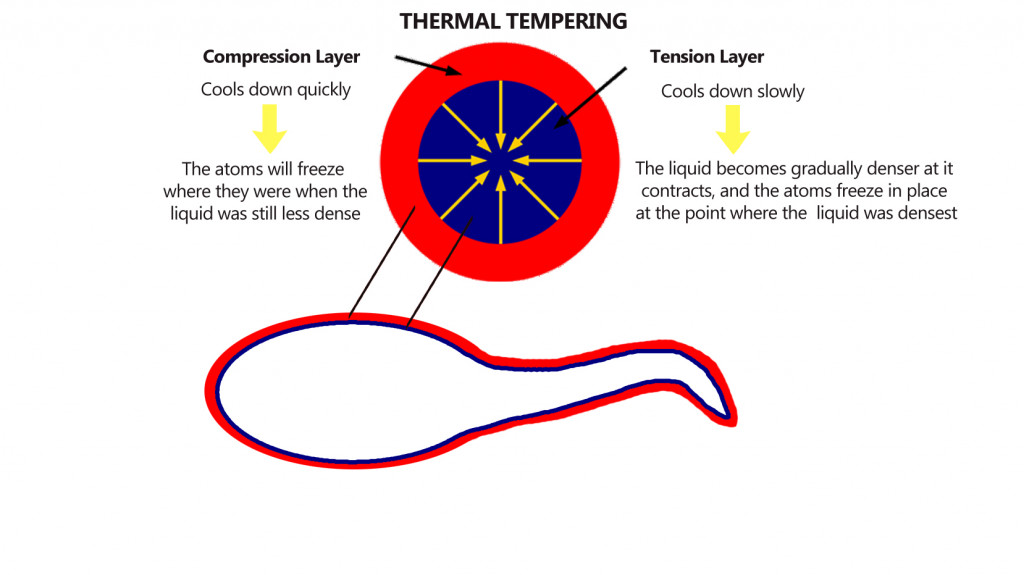

During quenching, the outermost surface of the glass droplet contacts the quenching medium first, which results in very rapid cooling. The core of the bulbous head, on the other hand, does not cool as rapidly.

This differential cooling results in the outermost part of the head experiencing high compressive stress, or forces that push molecules closer together. The inner part however, due to its slower cooling, experiences tensile stresses that force the molecules away from each other.

Experiments And Observations With Prince Rupert’s Drops

Amongst the most popular experiments using Prince Rupert’s droplets is the bullet test, where these glass bulbs are suspended and shot. It is observed that the head of the drop can withstand the impact of a bullet reasonably well. However, as shock waves travel to its tail, it causes the entire drop to disintegrate in an explosive way. The same effect can be observed if the tail is snipped by itself.

Until the advent of high-speed imaging technology, the physics behind Prince Rupert’s drops’ dual behavior was largely unknown. This is due to the fact that they explode into fine powder almost instantly, so changes in their structure could not be reliably recorded.

Also Read: When Glass Freezes, It Often Breaks. Why?

The Reason For Prince Rupert’s Drops’ Dual Behavior

The answer to this anomalous behavior lies in the structure of the drop. The drop is formed in such a way that the outer surface cools fastest, whereas the inner portion cools slowly.

This results in the inner portion pulling the outermost surface inwards, creating high compressive stresses. These compressive stresses can be as high as 700 megapascals. The interior of the droplet cools slowly, however, and even has vacuous bubbles that indicate the presence of stress, even in the absence of loading. Due to slow cooling, the interior of the drop experiences high tensile force that gets stored along the tail as energy.

For the drop to shatter, the stressor must act directly in the zone of tension, as such interaction will cause the accumulated energy to release explosively. This can be done by applying excessive loads on the bulbous head of the drop, or disturbing the tail directly.

While the large compressive layer on the head is strong enough to withstand bullets, the shockwaves generated by the impact can disturb the tail enough to cause the drop to shatter. At the same time, the simple act of snipping the tail can release all the tensile stress in a violent manner, causing the entire drop to disintegrate, as shown in the clip above.

Also Read: What Is The Shape Of A Raindrop?

End Note – Further Reading

The idea of Prince Rupert’s drops was no accidental discovery, and it does have precedent in nature. The quenching of glass was originally studied in volcanic lava that would flow down to nearby rivers in a molten state and form glass. This glass exhibited the same mechanical properties that are seen in Prince Rupert’s droplets.

A similar application of differential cooling from quenching glass is the Bologna bottle. While its outer surface is strong enough to hammer a nail through wood, the inner surface is so fragile that even a minor scratch causes it to shatter completely. Today, differential cooling rates due to the quenching of glass also find use in toughened glass (commonly known as tempered glass), which exhibit similar properties to Prince Rupert’s drops.

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- The science behind the Prince Rupert’s Drop – Scientific Scribbles - blogs.unimelb.edu.au

- Aben, H., Anton, J., Õis, M., Viswanathan, K., Chandrasekar, S., & Chaudhri, M. M. (2016, December 5). On the extraordinary strength of Prince Rupert's drops. Applied Physics Letters. AIP Publishing.

- 1. HEAT TREATED GLASS (TEMPERED & HEAT .... fgi.jo