Table of Contents (click to expand)

Rapamycin was isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus, a bacteria found in the soil of Rapa Nui. The discovery was made by Surendra Sehgal in the 1960s. The drug has since revealed to scientists a new biological pathway that allows us to better understand the immune system, aging, and cancer.

New discoveries can come from very unexpected places. The mystery drug, Rapamycin, came from a box of soil on one of the world’s most isolated places—Easter Island. The name of the indigenous community of the island and the native name of the island are one and the same: Rapa Nui. Though the drug was discovered more than a generation ago, it took decades of commitment to unravel its intricate secrets.

Who Was Surendra Sehgal And What Did He Discover?

In 1960, a Canadian expedition landed on the shores of Easter Island to investigate the origin of the iconic moa statues of the Rapa Nui people. Among some of the evidence they collected were soil samples from various points on the island. An Indian immigrant working in a biomedical company was sent one of these samples and grew what he found in the soil on agar plates. He hadn’t expected to find anything, but to his surprise, he immediately found a use for the Rapa Nui soil. The incredible history of the drug and how it was discovered has been described on this RadioLab podcast.

Rapamycin was isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus, a bacteria found in the soil of Rapa Nui. When the isolated drug was plated on fungus, it stopped the fungus from growing entirely, like a powerful antifungal medicine. The company Sehgal worked for wanted to market it as a topical antifungal cream, but why did the drug pause fungal growth so dramatically?

Upon investigating further, Sehgal found something even more shocking. In clinical trials with human subjects, the drug depleted the white blood cell count, meaning that it stopped the immune system from working! A drug that pauses immunity would not work to treat an infection, so the company shelved his work.

At the same time, the company’s labs were being relocated from Montreal to New Jersey. As the lab cleaners threw bottles of rapamycin in the bin, Sehgal retrieved his samples of rapamycin from the trash and brought them home. Sehgal stored them in ice cream cartons and transported them with his belongings across the border. He had an inkling that he was onto something, and wasn’t willing to give up so quickly.

During the 1980s, organ transplants were beginning to be performed across North America, but doctors were consistently running into an obstacle. The recipient’s immune system would often attack the donor organs, and rejection would kill the recipient just a few weeks after the transplant, even if the transplant was successful.

Researchers around the world were looking for a class of drugs known as immunosuppressants, which would subdue the immune system and prevent organ rejection. In 1983, the first immunosuppressant began to be used in hospitals. In 1996, the FDA approved a drug named FK-506, which first helped with liver transplants, and then with others.

Sehgal remembered his mystery drug’s ability to prevent immune action in similar ways, and wrote a memo to his company in 1988 about reopening Rapamycin research.

In the 1990s, an FDA trial was approved for the use of Rapamycin in transplants. After the drug was modified due to a patent expiry, it was approved.

In 1990, Sehgal was diagnosed with colon cancer and given six months to live. Knowing that he had work and family to live for, he refused to accept the diagnosis and took Rapamycin himself. Sehgal lived for five more years. Now, researchers are finding that Rapamycin can increase longevity in mice, leading to a mouse named Ike reaching 120 in mouse years!

This miracle drug isn’t a cure-all. It does not work on all cancers, and newer generations of immunosuppressants have succeeded Rapamycin in organ transplant patients. Even so, Sehgal’s refusal to give up on his soil from Rapa Nui saved thousands of lives.

Also Read: Can Microbes Eat Radiation?

How Does Rapamycin Do These Incredible Things?

Knowing that he had something huge on his hands, Sehgal sent samples of his mystery drug to people across the country. One researcher, David Sabatini, decided to use his PhD studies to investigate how this drug works. He found that it stops the growth of cells, tricking them into thinking they don’t have enough nutrients to divide. This deception also worked on cancer cells. Once tumor cells were convinced they had no nutrients to grow, they stopped dividing, and the cancer died off.

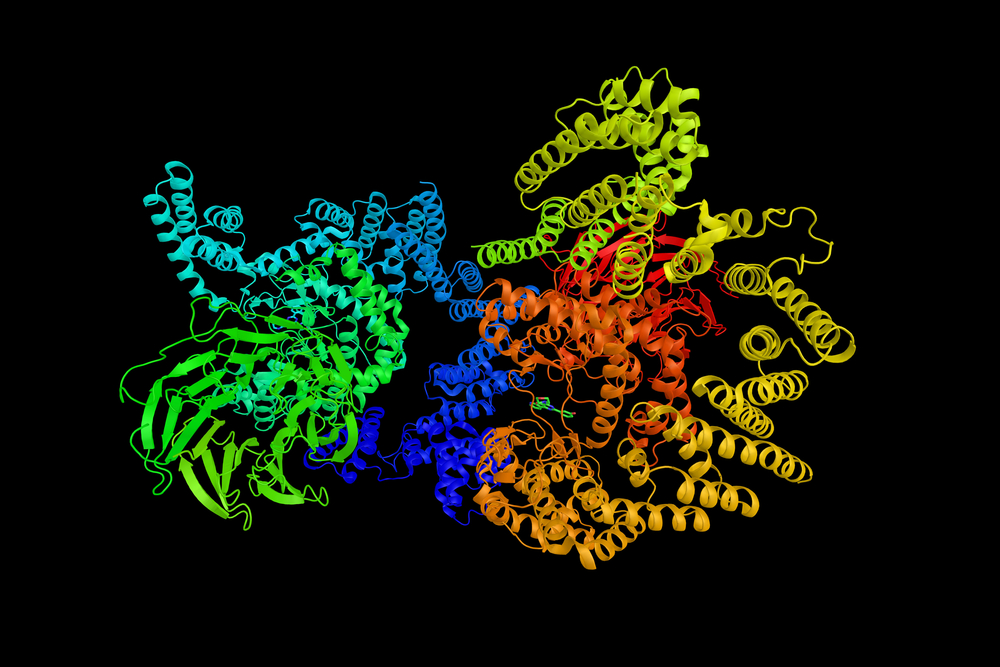

Deep within each of our cells is a large protein shrouded in mystery. For decades, microbiologists knew about this protein, but didn’t know what it did or why it was there. Rapamycin helped them figure out what it was for. By tracing the journey of Rapamycin through the cell, they found that the target was this mystery protein. They termed it mTOR, standing for Target of Rapamycin.

The mTor protein is the manager of an incredibly long chain of reactions that trigger a cell to divide in two, a process known as cell division. Cell division is a very energy-intensive process for the cell, requiring a lot of energy, nutrients and stability. A cell recognizes whether it has enough of these resources through a cell-signaling pathway. Each step on this long pathway confirms that, “Yes, there’s enough protein”, “Yes, there’s sugar”, and “Yes, there’s enough ATP”. The confirmation is reported back to mTOR, the manager. Rapamycin blocks this confirmation, tricking the cell into thinking it does not have enough nutrients to divide.

By tricking the cell into thinking it’s starving, the sequence of reactions is stopped and the cell does not divide. This is what stopped the fungal growth, prevented an overactive immune response in organ recipients, and slowed the growth of Sehgal’s own colon tumors.

Also Read: How Are Medicines Made?

How Did Surendra Sehgal Get So Lucky?

One box of soil, containing a mystery compound, traveled halfway across the world, and after decades of research, came to save the lives of thousands.

New compounds are waiting in the soil beneath our feet, in trees, plants and all around us. For centuries, ancient healers used willow bark to treat life-threatening fevers, and it was later discovered to be a source of Aspirin. The Foxglove plant contained a compound called digitalis, which is now used to treat congenital heart failure. Penicillin was the result of an accidental halt of growth on one of Alexander Fleming’s Petri plates. Even agar-based Petri plates were a stroke of accidental genius from the wife of a lab worker who drew inspiration from jams and jellies.

All we need to do is pay a little attention to life around us, and approach the natural world with respect, curiosity and wonder!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Diamond, J. (2007, September 21). Easter Island Revisited. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Arriola Apelo, S. I., & Lamming, D. W. (2016, May 21). Rapamycin: An InhibiTOR of Aging Emerges From the Soil of Easter Island. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Yoo, Y. J., Kim, H., Park, S. R., & Yoon, Y. J. (2017, May 1). An overview of rapamycin: from discovery to future perspectives. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Sarbassov, D. D., Guertin, D. A., Ali, S. M., & Sabatini, D. M. (2005, February 18). Phosphorylation and Regulation of Akt/PKB by the Rictor-mTOR Complex. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Seto, B. (2012, November 15). Rapamycin and mTOR: a serendipitous discovery and implications for breast cancer. Clinical and Translational Medicine. Wiley.

- The Dirty Drug and the Ice Cream Tub - Radiolab. Radiolab

- Samanta, D. (2017). Surendra Nath Sehgal: A pioneer in rapamycin discovery. Indian Journal of Cancer. Medknow.