Table of Contents (click to expand)

The Google effect is the tendency for people to forget information that can be easily looked up online. This effect is caused by the ease of access to information that search engines like Google provide. When people believe that they can easily find the answer to a question online, they are less likely to remember that information themselves.

The Google effect is defined as our tendency to forget information which can be promptly Googled. It was first demonstrated by Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Liu and Daniel Wegner in a paper published back in 2011.

Richard Feynman, in one of his lectures, described the computer as a mindless librarian. When you enter a vast library with a torn note on which is written the book you are looking for, all the librarian does is tediously search for the book amongst the thousands of books the library houses. However, with the advent of the Internet, the library expanded exponentially. Eventually, to access this new, voluminous labyrinth of information, Google was developed. And finally, along with the library, the repertoire of capabilities possessed by its librarian also expanded, exponentially.

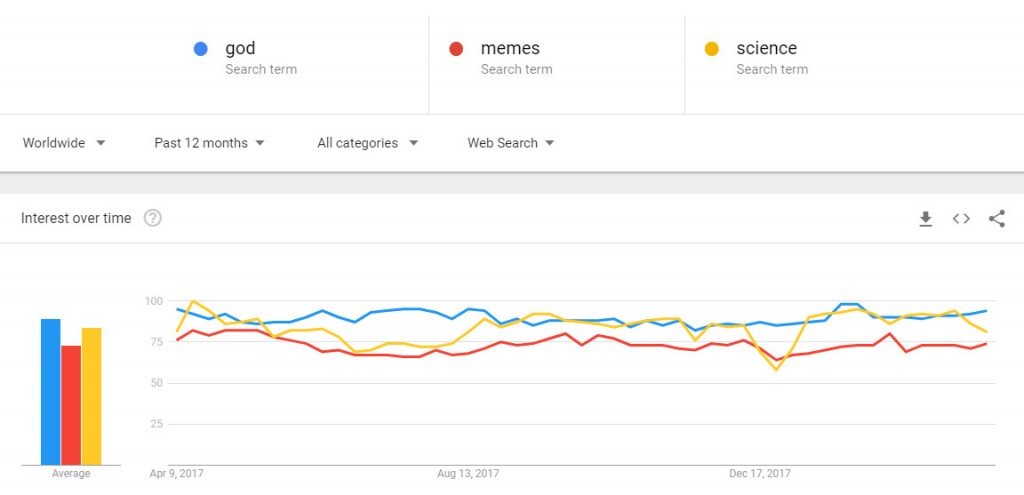

I use ‘Google’ rather than the generic term ‘search engine’, as today they seem to be one and the same. Google’s monopoly in search engine technology is so overwhelming that it is subject to no less than 3.5 billion inquiries every day. This includes conspiracies, trivia about film stars you love or loathe, comparisons, validating reviews, memes, science, restaurants in your vicinity, translations, an immensely constructive dictionary, newspaper articles criticizing Google itself, why we hate long lists, especially when the objects are distinguished by commas, as well as all the idiotic or sleazy things you search that make the employees of Google shake their heads in shame and question the conscience of the human race.

What’s more, Google’s complex algorithms have rendered the librarian shockingly efficient. The autocomplete feature or its famous “suggestions” make it appear almost telepathic. The inquiry doesn’t even have to be correctly spelled; one can type like a slurring drunk and Google will still understand the intended message. This convenience further worsens our dependence on it. But is this dependence bad for us, like any other dependence? Four experiments have concluded that it might be. Other than its omnipresence and the constant surveillance that has actualized George Orwell’s worst nightmare, it might also be making us more stupid and forgetful. This ‘digital amnesia’ is popularly called the “Google” effect.

The Google Effect

The Google effect is defined as our tendency to forget information that can be promptly Googled. It was first demonstrated by Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Liu and Daniel Wegner in a paper published back in 2011. The experiment was conducted in four parts, where the subjects were instructed to perform different tasks in each part. The results revealed that people were less likely to remember information that they believed was saved and could be accessed at any time.

In the first experiment, subjects were asked a number of yes or no trivia questions. The questions would appear in blocks, categorized as either easy or difficult. After answering the question, the subjects underwent a modified Stroop test. A Stroop test is a very popular psychological test that I’m sure everyone has taken at least once in their lifetime. A subject is shown a list of words written in different colors. However, to confuse the subject, the colored word on the screen is chosen to be the name of a color different from the color it is printed with, for instance, the word “red” written in green letters. The subjects are then asked to name the color, rather than the word. The Stroop test gives us a measure of the processing speed or reaction time of our conscious mind.

However, Wegner’s test was different. The words his team flashed were a mix of non-technological and technological words, such as “screen” and “Google” printed in either red or blue. They observed that the subjects demonstrated a slower response time when they encountered technological words, especially when they occurred after they answered a difficult question. They found that the difficult trivia question disposed or primed them to think about computers. They concluded that “it seems that when we are faced with a gap in our knowledge, we are primed to turn to the computer to rectify the situation.”

In the second experiment, the subjects were asked to read 40 trivia statements. Half of the subjects were led to believe that the statements were saved and could be accessed later, while the other half was explicitly instructed to remember them, as the statements were going to be erased. When subjects were later asked to recall the statements, the ones who believed that the statements had been saved were highly unlikely to remember them. They displayed a higher tendency to forget, just like students who think that what they study for an exam will serve no later purpose.

In the third experiment, the subjects were asked to read and type trivia statements on a computer. A few of them were told the entry would be erased, a few were told that it would be saved, and the remainder were told not just that the entry would be saved, but also where it would be saved. The subjects were then put up to two tests. The first test required them to recognize whether a slightly altered statement presented on their screen was the same as the one they had typed. The second asked them whether this statement was saved or not, and if yes, where was it saved?

The team observed that people could either remember the content or the location where it was saved, but seldom both. In fact, most of them could only remember the saved information’s location, and not the information itself. The fourth experiment was similar to the third, except that all the statements were read, typed and saved in a folder with a generic name, such as “items” or “facts”. Now, they could either recall both the statement and location, either one of them, or neither of them.

Their results were similar to the results of the third experiment: subjects were highly likely to remember the locations of the saved content, rather than the content itself. They would, as if by some subconscious laziness, choose to remember the locations even when the statements could be readily memorized. Of course, this feature allows us to save more time and memory space, but most importantly, it relieves us of conscious toiling.

Also Read: Why Do We Tend To Remember Only The First Few Items Of Our Grocery List?

What Causes The Effect?

While making a conscious effort to learn, we must make two choices: what information is important enough to remember and what details deserve our precious attention. However, knowing that an external memory drive is storing every speck of information out there, we tend to devalue both choices. We forgo the choices and the virtue of learning something new right along with them. This laziness or casualness extends beyond facts to personal information – when was the last time you remembered a phone number or didn’t set a reminder for an important event?

The researchers concluded that computers have become a part of our transactive memory. Transactive memories are useful in social groups where individuals of a certain expertise possess information that another member of the same group might lack. This individual, however, due to his own expertise in a different subject, might possess information the former individuals might lack.

All the members, like the team in The Italian Job, therefore share a symbiotic relationship where one can access new information by asking another member. It seems that we have incorporated computers into the same relationship, by way of expanding our distributed cognitive system. The paper reads: “one could argue that this is an adaptive use of memory—to include the computer and online search engines as an external memory system that can be accessed at will.”

Transactive memory has been beneficial for humans since we lived in caves. Eventually, we began jotting in notebooks, journals and diaries. The computer seems to be the next great addition to our myriad tools. This is no doubt lucrative – we have finally befriended someone who is an expert in everything. However, it also has its fair share of disadvantages. Studies have consistently shown that information learned through the Internet is recalled with less accuracy and confidence, as compared to learning through a hardcover book.

The former process showed less activity in parts of the brain associated with the conscious reconstruction of a stored memory. Lastly, we must be constantly plugged in to access the glut of information online. Without the wire, Google is just an 80s adventure video game about a T-Rex hopping and ducking in a forgotten, pixelated world. it may be fun, but it’s no more edifying than a blank textbook.

Also Read: How Are Memories Stored And Retrieved?

How well do you understand the article above!