Table of Contents (click to expand)

It is generally believed that healthy people get déjà vu due to a memory error evoked by the mismatch between sensory input and memory-recalling output. This explains why we occasionally get a feeling of ‘familiarity’ through déjà vu, but it’s not as tangible as a fully recalled memory.

Have you ever experienced the strange feeling when you look at something and think, “Hey! I’ve seen this before it seems”. This may be something that you’re watching for the first time in your life—even in a place where you have never been. Even so, there is still a bizarre tickle at the back of your mind, telling you that somehow you are already familiar with the situation before you. It can be a bit unnerving, and also fascinating, and almost everyone in the world has felt it at some point, even if they didn’t know the word for it!

What Is Deja Vu?

This feeling of being vaguely ‘familiar’ with something that you likely have never seen before is called déjà vu. To put it a bit differently, déjà vu is the eerie sense that our present experience is a reminiscence of something that we can’t really figure out. We tend to subtly acknowledge that there’s something a little “off” with this feeling of familiarity.

Déjà vu is a French phrase that means ‘already seen’. You may even be reading this article, sitting at your house right now, and your brain could suddenly tell you “Hey! I’ve read this article before!”

Also Read: Why Do People Feel Nostalgic And How Does It Affect Them?

Why Does Deja Vu Happen?

Déjà vu is also associated with the beginning of a seizure in epilepsy. For a patient of epilepsy, the feeling of déjà vu could mean that they might begin to lose consciousness.

The study was conducted by Adam Zeman, a clinical neurologist in the UK, and his team to determine how epileptic déjà vu is different from the usual déjà vu experienced by healthy individuals. The difference was minimal, except the higher frequency of occurrence in the case of epileptic patients.

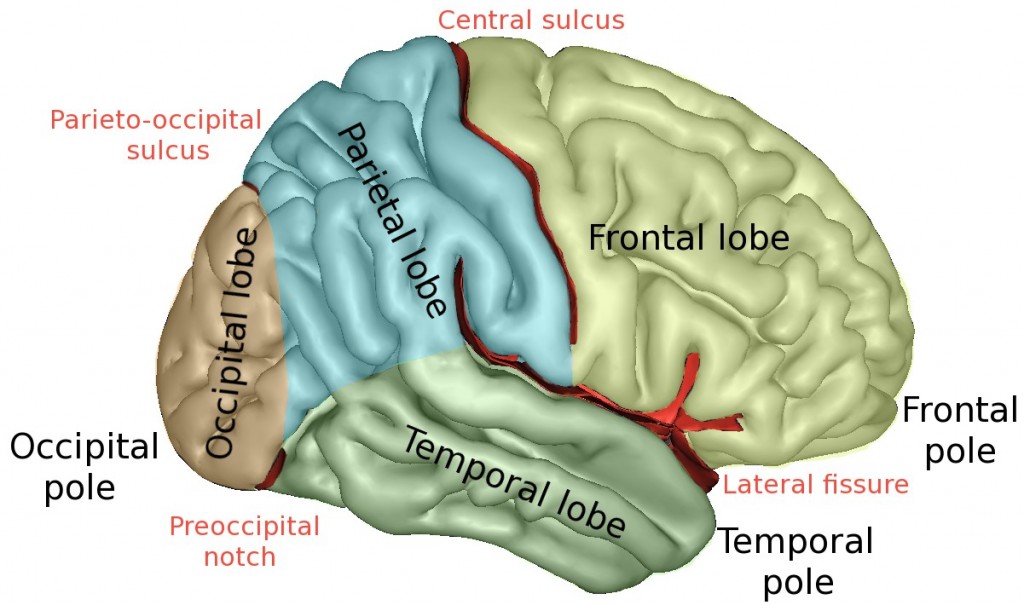

In fact, a study related to déjà vu began as early as the 1950s, wherein researchers tried to find what regions of the brain were responsible for it through electrical stimulation. In the 1970s, a method to artificially induce déjà vu was discovered using electrodes in the medial temporal lobe of the brain. Contemporary studies have even identified specific parts of the medial temporal lobe linked to the occurrence of déjà vu. The hippocampus and the parahippocampal gyrus, both of which are important in maintaining memory in the human brain, are located in the medial temporal lobe.

Zeman has noted that researchers earlier assumed that déjà vu was a phenomenon of the hippocampus—our brain’s memory data center. However, newer studies have identified the involvement of adjacent areas like the perirhinal cortex, an area associated with recognition, when things are familiar. This ‘recognition’ is different from ‘recollection’. Let’s try to understand this with an example.

Imagine that your dad walks into your room and you glance over at him. At this moment, you have a ‘familiarity’ response. That’s a little different from ‘recollection’. Recollection would be something like asking yourself after that glance, “Who is that man? Someone I saw last weekend in a cafe?”

So, the present theory is that epileptic déjà vu is the result of unusual electricity discharges in the brain’s “familiarity” region. When this region becomes hyperactive, the person feels familiar, but that feeling is not complemented by recollection, which makes the experience surreal.

Now, the main question that arises is why does a supposed warning bell for a seizure—the déjà vu—manifest in people who are not suffering from epilepsy? One theory is that déjà vu is a miniature version of a seizure that even healthy people experience. Renowned Canadian neurosurgeon Wilder Pentfield called déjà vu a “little seizure”, but this moniker is disputed by other researchers in this field. Zeman noted that it’s hard to find any evidence because healthy people do not get their intracranial brain activity recorded.

That being said, it is generally believed that healthy people get déjà vu due to a memory error evoked by the mismatch between sensory input and memory-recalling output. This explains why we get a feeling of ‘familiarity’ with déjà vu, but it’s not as tangible as a fully recalled memory. A study discovered that there might be a subtle volume reduction in the medial temporal lobe associated with healthy people experiencing déjà vu.

Also Read: The Doorway Effect: Why Do We Forget What We Were Supposed To Do After We Enter A Room?

Variants Of Déjà Vu

The classic definition of déjà vu is a sense of ‘familiarity’ with your present experience that you consciously or subconsciously know is false. However, déjà vu has certain variants with their own peculiar characteristics. One of them is déjà vécu.

Déjà Vécu

Déjà vécu translates into “already lived the moment”. People experiencing déjà vécu don’t only get a feeling of familiarity, but they also feel as if they have already lived the moment before. They even feel as if they know what’s going to happen next! Déjà vécu can be like being on the verge of pointing out déjà vu, with an added feeling of ability to sense what’s going to happen next. From a physiological standpoint, researchers have found that déjà vu comes from the perirhinal cortex, a region responsible for the feel of familiarity. On the other hand, déjà vécu would be coming from the hippocampus, because it’s more like an erroneous recollection.

Déjà-rêvé

Another variant is a déjà-rêvé. In déjà-rêvé, there is an intense recollection of one’s dreams. Studies have found that this is a result of electrical stimulation in the brain similar to those who experience epilepsy.

Confabulation

Another condition commonly confused with déjà vu and déjà-rêvé is confabulation. Generally, when déjà vu occurs, we consciously or subconsciously know that something is wrong in our perception. We know that our feeling of familiarity is fake and we soon dismiss it, but some do not. They are so seduced by this feeling of familiarity that they try to find reasons to justify the familiarity. In this process, they end up inventing stories as past experiences which are simply imaginary and not true. This is a memory disorder that is medically called confabulation.

Who Is Most Prone To Déjà Vu?

Déjà vu, despite feeling so unnatural, is quite common. Nearly two-thirds of the population have experienced déjà vu at some point in their life, although it only lasts for a few seconds in most cases. It can also be invoked due to emotional stress and fatigue.

Children rarely experience déjà vu, whereas young adults in their 20s and 30s are more likely to experience déjà vu. Your chances of experiencing déjà vu diminish thereafter. The occurrence of déjà vu in old age is likely to be associated with epilepsy and seizures.

Also, studies suggest that people who pursue education for longer are more likely to get déjà vu. Déjà vu is more likely to occur during the night than the day. People who are using serotonin-based drugs and medicines are also more susceptible to déjà vu. Frequent travelers who are able to remember their dreams longer are also highly likely to experience déjà vu.

A Final Word

Finally, for those people who have never had déjà vu and are still reading this article, it’s admittedly hard to fathom what déjà vu is. It’s a puissant feeling, a subjective one that’s hard to explain and even harder to study. That is why scientists and researchers have a hard time academically quantifying this feeling to find the reasons behind it. It probably involves intricacies and processes of our senses, brain, memory, retrieval, and recollection. In fact, there are even some researchers who haven’t experienced anything like déjà vu and are therefore skeptical that it even exists! For them, other researchers working on déjà vu may seem like they’re doing research on a ghost!

Test how well do you understand déjà vu

References (click to expand)

- Warren-Gash, C., & Zeman, A. (2013, January 11). Is there anything distinctive about epileptic deja vu?. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. BMJ.

- (1959) Illusions of comparative interpretation and emotion - PubMed. The United States National Library of Medicine

- Brázdil, M., Mareček, R., Urbánek, T., Kašpárek, T., Mikl, M., Rektor, I., & Zeman, A. (2012, October). Unveiling the mystery of déjà vu: The structural anatomy of déjà vu. Cortex. Elsevier BV.

- Illman, N. A., Butler, C. R., Souchay, C., & Moulin, C. J. A. (2012, March 20). Déjà Experiences in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Epilepsy Research and Treatment. Hindawi Limited.

- deja vu | Common Errors in English Usage and More. Washington State University

- O’Connor, A. R., & Moulin, C. J. A. (2010, March 30). Recognition Without Identification, Erroneous Familiarity, and Déjà Vu. Current Psychiatry Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.