Table of Contents (click to expand)

Given the data, it’s likely that unconscious individuals (specifically, people in the minimally conscious state) do experience pain.

One reason why pain is difficult to study is that our subjective experience of pain (how it “feels” to feel pain) and physical manifestations of pain (having pain receptors and the brain’s recognition of pain) are different. After all, animals have pain receptors, but we don’t know if they “feel” pain the same way we do.

Interestingly, consciousness (and self-awareness) was considered an important criterion for an organism to “feel” pain, which is why psychologists thought babies couldn’t feel any pain for a very long time. Imagine that!

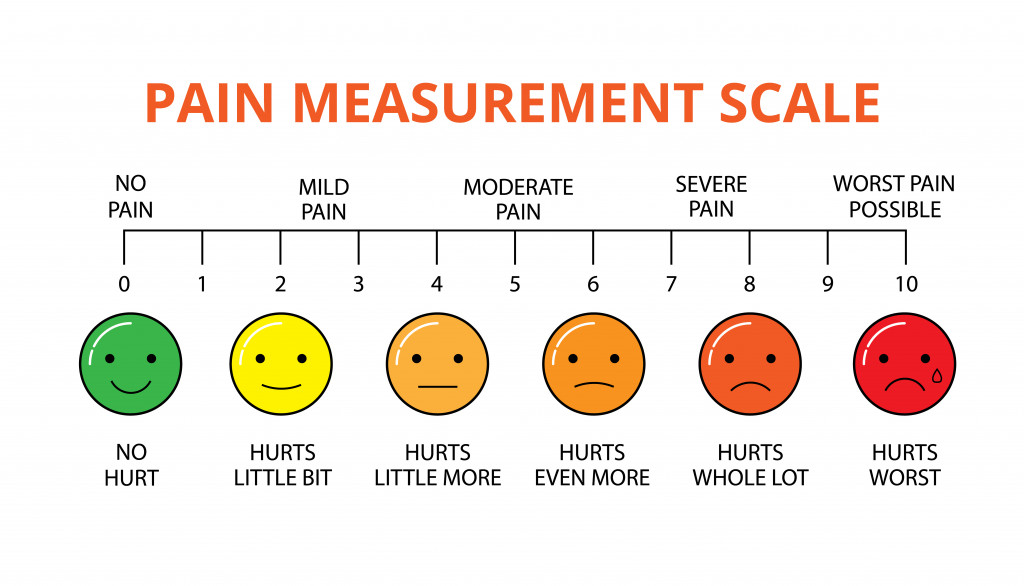

Given that, usually, we can only tell if someone is in pain and to what degree if we ask them, but what about when we’re unconscious?

What Does Science Say?

One way to investigate this idea is to ask caregivers or attenders who frequently deal with unconscious people. When medical doctors were asked, in a 2009 study, whether people in a vegetative or unconscious state could experience pain, 56% of them said yes, and 68% of paramedical caregivers also concurred.

We can’t solely rely on their word though. It has been historically unwise to conclude from subjective second-hand experiences, even if they come from people we consider experts on the issue. After all, one’s mind can be deceptive. It’s possible to mistake any response as a response to pain. To avoid falling into the same trap, we must start by looking at the physiology of the brain and go from there.

In a 2010 study led by Caroline Schnakers—whose team at the Coma Science Group studies pain—made a distinction between how the brain receives pain and how the subject experiences pain and responds to it. It is possible for the brain to receive pain signals without the person in question “feeling” or expressing it. Additionally, the researchers distinguished between a vegetative state—determined by a visible lack of response to any stimulus—and a minimally conscious state, where some repeatable response to a stimulus can be detected.

Schnakers and the team showed PET scans of brains in the VS, MCS, and healthy states taken from a paper led by Mélanie Boly. These scans indicate that unconscious individuals do respond to pain on some level.

Also Read: How Does Anesthesia Work?

How Pain Works In The Brain

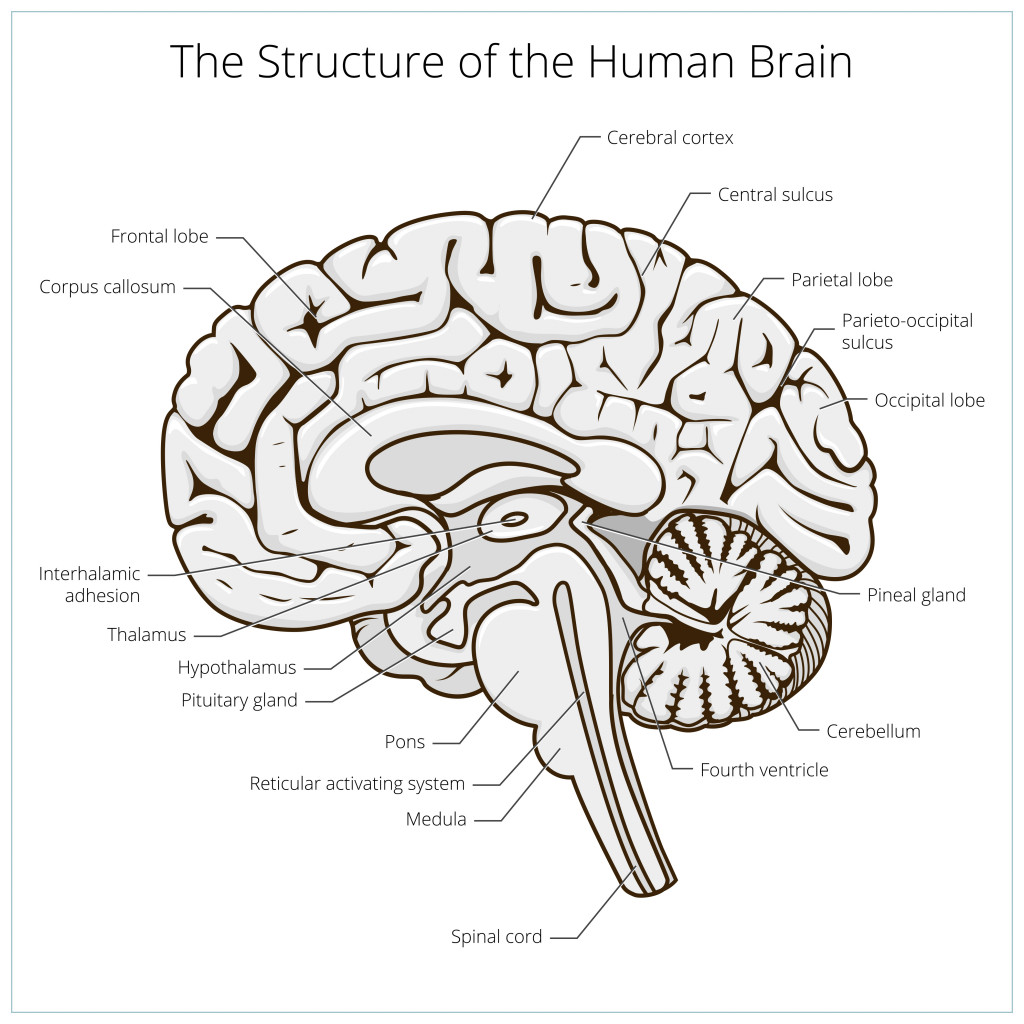

The brain is a complex organ, so not every process in the brain can be accounted for; the amount of information is simply too much to handle. To make things more manageable, psychologists tend to record which parts of the brain respond to particular stimuli and try to assign certain functions to the activated parts based on the stimulus administered. These tend to be generalizations, but they get the job done!

Applying the same methodology, scientists qualitatively split the experience of pain by the brain into three parts: the “cognitive-evaluative”, the “motivational-affective”, and the “sensory-discriminative”, which in simpler terms means the emotional response we have to pain, how pain affects our motivation, and the brain’s sensory experience of pain, respectively. What we’re interested in is the brain’s experience of pain, and how it perceives it.

The pain-related part of the brain is mostly controlled by parts of the thalamus, the frontal cortex and the connections between them (along with other parts of the brain). Schnakers’ team also found a difference in how the sensory-discriminative part of the brain responded to pain in patients in the vegetative state vs. those who were minimally conscious. In patients in the vegetative state, the cortex appeared to react strongly to pain, running many cortical processes, but there was a disconnection observed in the neural pathways between the thalamus and cortex and within the cortex. In minimally conscious patients, however, such a disconnect was not found. Additionally, there was a clear activation of the anterior cingulate—connected to pain experience—which wasn’t found in patients in the vegetative state.

Also Read: Why Do We Forget Pain When We’re Engaged In Another Activity?

Conclusion

Given the data, it’s likely that unconscious individuals (specifically, people in the minimally conscious state) do experience pain. However, there still isn’t enough research being done on pain, at least, not enough to comfortably compare degrees of pain or even detect it in some cases.

The study of the mechanism and experience of pain has wide-reaching consequences on how patients ought to be treated. If accurate estimates of the pain felt by unconscious patients aren’t made, doctors could risk over-administering or under-administering pain medication, both of which are problematic. Giving too little medication risks hurting the patient, whereas giving too much runs the risk of excessively sedating the patient and missing signs of returned cognition.

A lot is riding on such research. Sam Harris, a popular psychologist, in his book “The Moral Landscape”, argues that secular moral objectivity can be achieved once we can detect and quantify pain (and pleasure) properly. The burden of all secular ethics, therefore, rests on the shoulders of Science!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Anand, K. J. S., & Hickey, P. R. (1987, November 19). Pain and Its Effects in the Human Neonate and Fetus. New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society.

- Smith, G., Bartlett, A., & King, M. (2004, January 29). Treatments of homosexuality in Britain since the 1950s—an oral history: the experience of patients. Bmj. BMJ.

- Boly, M., Faymonville, M.-E., Schnakers, C., Peigneux, P., Lambermont, B., Phillips, C., … Laureys, S. (2008, November). Perception of pain in the minimally conscious state with PET activation: an observational study. The Lancet Neurology. Elsevier BV.

- Borsook, D., & Becerra, L. R. (2006, January 1). Breaking down the Barriers: fMRI Applications in Pain, Analgesia and Analgesics. Molecular Pain. SAGE Publications.

- Demertzi, A., Schnakers, C., Ledoux, D., Chatelle, C., Bruno, M.-A., Vanhaudenhuyse, A., … Laureys, S. (2009). Different beliefs about pain perception in the vegetative and minimally conscious states: a European survey of medical and paramedical professionals. Progress in Brain Research. Elsevier.

- Schnakers, C., Chatelle, C., Majerus, S., Gosseries, O., De Val, M., & Laureys, S. (2010, November). Assessment and detection of pain in noncommunicative severely brain-injured patients. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. Informa UK Limited.