Table of Contents (click to expand)

The urge to jump or high place phenomenon apparently springs from a distortion of our perceptions. Lab tests have shown that people estimate disgusting things like feces to be closer than they really are, or they underestimate the time when they abruptly encountered a snake, as compared to when they met a butterfly.

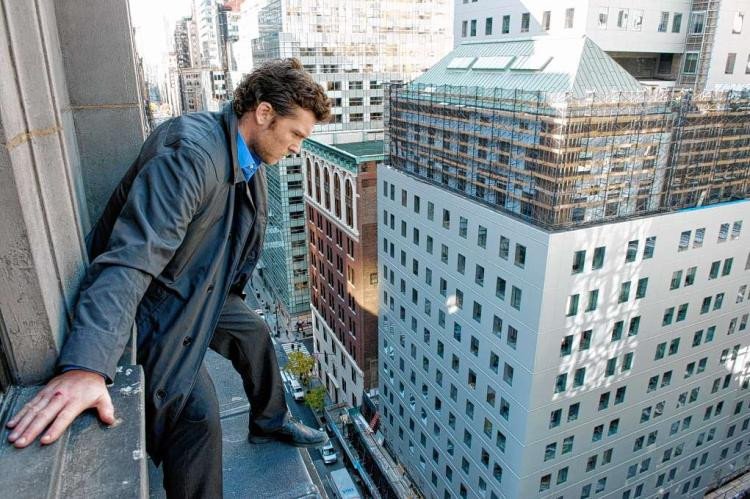

Of course, the French have a term for this – L’Appel du Vide, which translates to call of the void. Standing on the edge of a cliff, you feel a sense of precariousness creeping up on you… the abyss below beckons to you.

A phobia is an irrational fear of something and has always been fundamentally associated with anxiety or trauma. Acrophobia or fear of heights is one of the most common phobias, with one in 20 people estimated to suffer from it.

However, a fear of snakes would force me to run away from them, so the urge to jump seems paradoxical: if these people despise heights, why should they want to jump?

A Freudian would claim that this urge represents their repressed thoughts about contemplating suicide. This makes sense when we ask someone to justify the contrary claim; in other words, if one can recognize danger from the recoiling of his hand from a hot cup, why do we feel the need to jump when the railing fully protects us on a balcony? Surely, it means that you want to jump, right?

Freudians, however, are wrong about many things, including this. Research in cognitive science and clinical psychology shows that the urge to jump is related to our vestibular system, fear, and cognition.

High Place Phenomenon

Jennifer Hames, a clinical psychologist at the University of Notre Dame specializing in suicidal behavior, calls it the High Place Phenomenon (HPP). In a remarkable study including 431 subjects, she and her colleagues found that half of them had experienced the urge to jump at least once in their lives, even though they had never contemplated suicide. This refutes Freudian’s suicide ideation theory.

The urge apparently springs from a distortion of our perceptions. Lab tests have shown that people estimate disgusting things such as feces to be closer than they really are. People also underestimate the time when they are confronted with a frightening thing, such as a snake. Another example perceiving that the width of a plank on which they are walking is smaller than it really is.

Similarly, we overestimate vertical distances. This vertical bias tends to make heights scarier. As the height increases, so does our fear of it. Surprisingly, this distance bias is absent when it comes to horizontal distances. (Source)

The discomfort we feel on a ledge is eerily reminiscent of motion sickness. Motion sickness is caused by a dissonance between different sensory systems, which are crucial for maintaining balance. Symptoms arise mainly as a result of a conflict between our visual and vestibular systems. The vestibular system is responsible for spatial orientation, posture adjustments, and balance. The vestibular system is a tiny apparatus in the inner ear and consists of the utricle and saccule, which detect gravity for vertical orientation. Three perpendicular canals are filled with fluid to detect rotational movements.

If the vestibular system perceives movement, but the visual system does not, or vice versa, it triggers a conflict in the brain.

For the former, consider traveling on a boat. The vestibular system senses movement when we rock on the waves, but the eyes do not, which causes nausea.

For the latter, consider standing in a stationary bus while another bus moves forward in your line of sight. The visual system detects movement and deceives us for a moment into believing that we are moving. However, the vestibular system rightly contradicts this. This illusion causes a certain uneasiness, although higher thinking and memory later help us see past the illusion.

The dissonance disrupts our balance, so maintaining balance, as a tightrope walker does, requires arduous practice. People with poor postural control report a stronger urge to jump than people with steady footing.

In one study, participants performed a strange balance test (called the Tandem Romberg test): while barefoot, they were instructed to place their left foot in front of their right foot so that the heel of their left foot touched the toe of their right foot. Then, they had to cross their hands over their chest, close their eyes, and try to maintain this posture for two minutes.

You can try it at home and see how you fare.

A breeze, right? Many subjects could only do this for an average of 40 seconds! Those who endured two or more minutes were, as you might have guessed, less afraid of heights.

The obstacles created by distorted visual perception or overestimation, poor posture control, and flawed vestibular signals fuel the fears that we feel at the edge of steep heights – and they fuel our urge to jump.

Also Read: Fear Of Heights: What Makes People Nervous On Tall Structures?

The Brain Is Misinterpreting Safety Signals.

Hames describes the urge to jump due to the conscious brain misinterpreting alarm signals from the brain’s safety centers due to a delay in processing information.

The amygdala is part of the brain’s safety centers and detects potential threats in the environment. It works quickly and sends an alarm signal to the cortex when it detects a potential threat.

The cortex, however, processes information relatively slowly. It recognizes the signal but is unsure of the cause. This uncertainty is responsible for our sense of perturbation on a ledge.

This uncertainty is primarily due to the activation of the amygdala. It should come as no surprise that people who felt the urge to jump were often more anxious, as evidenced by their sweaty palms, increased heartbeat, and other common physiological symptoms of anxiety.

So is it necessarily bad to have a distorted perception or severe anxiety about falling to your death?

Of course not! It is your survival instincts that force you to retreat to a safer place. Jeanine Stefanucci, a leading psychologist, defends those who feel despair on edge by assuring them that “taking a step back is a good thing.”

Also Read: Why Do People Indulge In Extreme And Dangerous Sports?

Do you remember why one feels the urge to jump from high places?

References (click to expand)

- The Human Balance System - Vestibular Disorders Association. vestibular.org

- Hames, J. L., Ribeiro, J. D., Smith, A. R., & Joiner, T. E., Jr. (2012, February). An urge to jump affirms the urge to live: An empirical examination of the high place phenomenon. Journal of Affective Disorders. Elsevier BV.

- Vagnoni, E., Lourenco, S. F., & Longo, M. R. (2012, October). Threat modulates perception of looming visual stimuli. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- Teachman, B. A., Stefanucci, J. K., Clerkin, E. M., Cody, M. W., & Proffitt, D. R. (2008). A new mode of fear expression: Perceptual bias in height fear. Emotion. American Psychological Association (APA).

- Stefanucci, J. K., & Storbeck, J. (2009). Don't look down: Emotional arousal elevates height perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. American Psychological Association (APA).

- VISUAL ART IN APHASIA THERAPY: THE LOST AND .... actaneuropsychologica.com