Table of Contents (click to expand)

“Acquired taste” refers to the phenomenon of learning to prefer a flavor or food we initially do not like after repeated ingestion. When we do not feel any unpleasant experience with an unpalatable food, the brain updates this information, helping us ‘acquire’ a taste.

A huge percentage of people can’t imagine waking up and starting the day without their daily cup of coffee. This makes it hard to believe that some people actually hate the taste of coffee. Children, in general, hate the taste of coffee, and can’t fathom why adults buy themselves cups and cups of such a disgusting and bitter fluid!

No coffee lover starts out as one. The first cup of coffee elicits a uniform “ew” from every child. Yet some take up drinking coffee repeatedly and develop a liking for it.

Coffee is a popular example of what we call an “acquired taste”. Acquired taste is a preference for a food or flavor that is initially aversive to us, but develops over time with regular exposure. How does an acquired taste develop? And why do we ingest food that is unpalatable to us?

What Is An Acquired Taste?

Acquired taste is a taste preference that is developed through learning, so scientists call it “conditioned taste preference”. This learning can only happen through repeated exposure. For example, people who have an acquired taste for coffee develop it through repeatedly drinking it, despite their initial aversion to its bitter taste. A wide range of foods become palatable only through learning, such as asparagus, alcohol, raw oysters, and even fermented foods like kimchi.

Also Read: Why Does Bitter Food Taste Bad?

Conditioning Of Taste

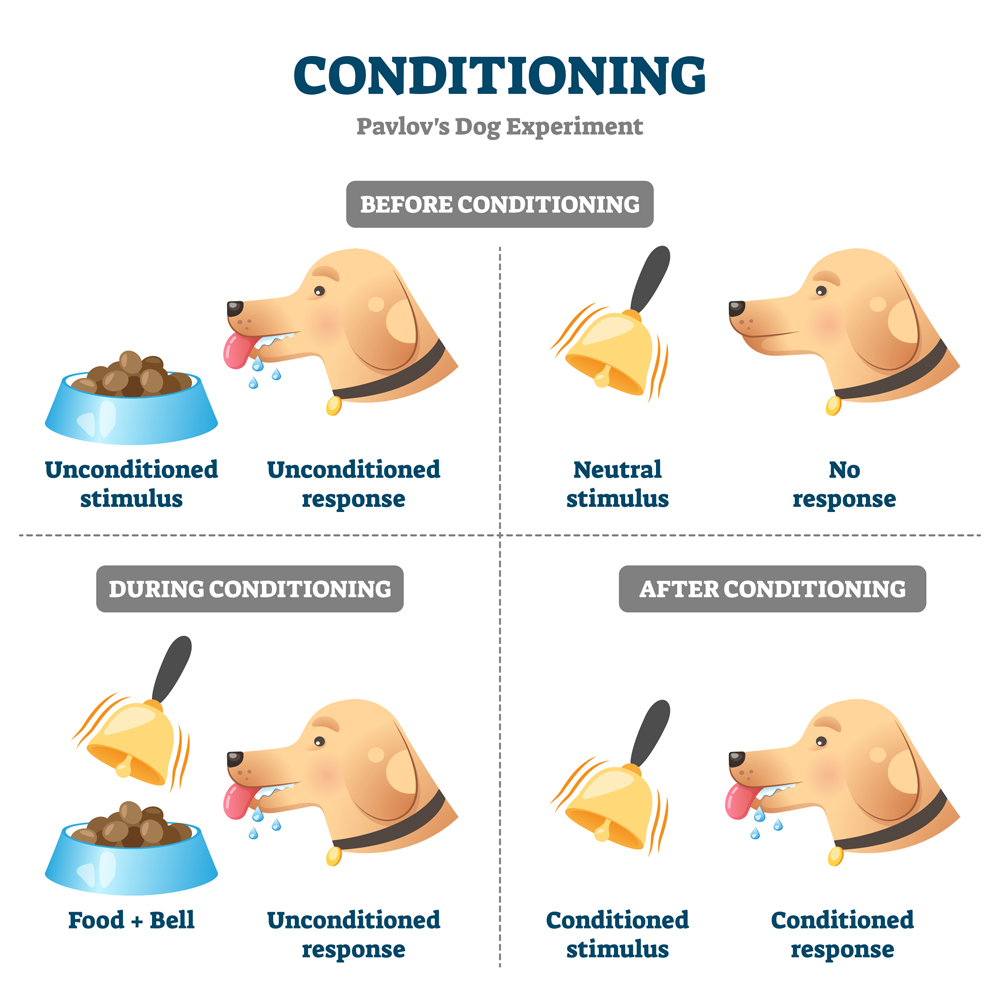

In behavioral psychology, the term ‘conditioning’ is used to explain a type of learning through which an inherent or innate pattern of our behavior is modified. This was first shown by physiologist Ian Pavlov in his experiment with a dog. He ‘conditioned’ the dog to salivate following the sound of a bell by repeatedly ringing the bell every time the dog was fed.

Here, salivation is a conditioned response (CR) to a conditioned stimulus (CS), which is the sound of the bell. Prior to learning, the bell doesn’t generate salivation. Thus, the inherent pattern of behavior has been modified through learning.

We have some inherent patterns of responses to taste stimuli too! We inherently hate food that is bitter in taste and prefer those that are sweet. Our brains are wired to respond in this way because food that is bitter more often than not has a chance of being toxic to us. On the other hand, food that is sweet most often contains energy. Therefore, even infants are shown to prefer sweet food and show an aversion to bitter food, demonstrating that we have these preferences set at birth. However, this behavior can be altered through conditioning, much like Pavlov’s dog!

Conditioned Taste Preference (CTP)

The avoidance or aversion to bitter food (unconditioned stimulus – US), such as coffee, is the unconditioned response (UR), or our inherent behavior.

When repeatedly presented with the bitter food or beverage, we start noticing that it doesn’t generate a bad sensation from the gut after consumption, and so it isn’t toxic. Also, we experience other benefits, such as the stimulating effects of having coffee. If we find this effect rewarding, the brain updates our response. Therefore, the next time we have coffee, we do not find it aversive or avoid it. With experience, we even seek coffee because its stimulating effects outweigh the initial bitter taste. This preference for coffee is called a conditioned response (CR) and coffee is now a conditioned stimulus (CS) to us. This phenomenon of altering an initially aversive taste to a preferred taste is called conditioned taste preference (CTP).

It is important to note that the taste experienced by our mouth of these acquired flavors remains the same – i.e., coffee always tastes bitter to our mouth. The brain only updates its ‘hedonistic value’ or the pleasure generated by its consumption with repeated exposure.

Conditioned Taste Aversion (CTA)

Conditioned preference is a case of modification of our behavior where we start preferring a certain food/flavor with exposure. However, the “learning of taste” can cause us to avoid certain foods as well. This is quite common in cases where people hate food with which they had a bad experience. Imagine having oysters in a fancy dinner at a restaurant that caused a bad stomach infection. Next time you see oysters, you may even feel a surge of nausea.

This kind of conditioning where we learn to avoid an initially palatable food due to bad consequences is called conditioned taste aversion (CTA).

This learning is important for our survival because we can learn to avoid food that causes discomfort or illness, and therefore avoid it next time!

Brain Pathways For Acquired Taste

We saw that in the case of both aversion and preference to taste, the initial response to the food gets modified with exposure. How does this happen?

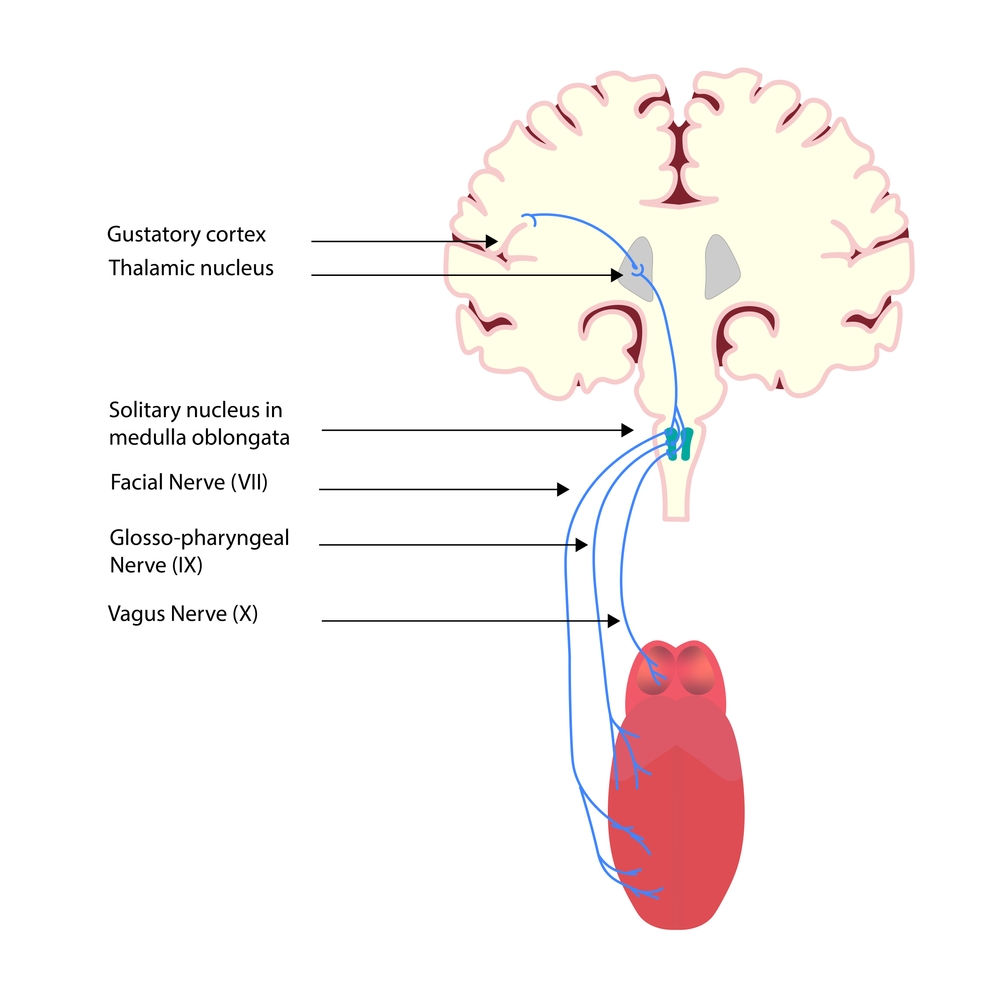

The taste buds in our mouth carry information about taste to the facial and glossopharyngeal nerves. These nerves transmit the information up to the thalamus, which acts as a relay center to the gustatory center of the brain, located in the insula.

The thalamus and the insular cortex interact with many regions, such as the amygdala, which regulates fear, reward-based (dopaminergic) pathways of the brain, such as the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens, as well as the hypothalamus, which modulates feeding behavior. Acquired taste is learned by modifying the signaling in these reward and fear memory pathways of the brain that interact with the gustatory center of the brain. Thus, the “hedonistic” value of a food can be changed based on our bad or good experience with it, and our response to it can be updated by the brain to either prefer or avoid it the next time you come across it.

Also Read: How Do We Taste Things?

Conclusion

Acquired taste refers to the phenomenon of learning to prefer a flavor or food we initially do not like, following repeated ingestion. When we experience no unpleasant side effects from unpalatable food, but instead feel an unexpected rewarding sensation, the brain updates this information, reducing our aversion to it. This occurs because parts of the brain that control information on reward and learning interact with the taste center of the brain.

This mechanism is central to our survival because it helps us avoid food that is harmful to us, and ingest those that we find rewarding or nutritive. It is thanks to this mechanism that you’re able to enjoy your morning cup of coffee, despite its inherent bitter taste, and get that buzz! And if your child hates asparagus or raw oysters, the key is to make them try it again… good luck!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Harris, G., & Mason, S. (2017, April 29). Are There Sensitive Periods for Food Acceptance in Infancy?. Current Nutrition Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Cornelis, M. C., & van Dam, R. M. (2021, December 13). Genetic determinants of liking and intake of coffee and other bitter foods and beverages. Scientific Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Yamamoto, T. (2006). Neural substrates for the processing of cognitive and affective aspects of taste in the brain. Archives of Histology and Cytology. International Society of Histology & Cytology.