Table of Contents (click to expand)

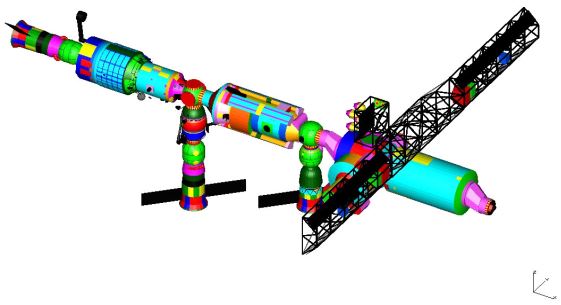

The ISS and other satellites protect against large pieces of space debris by re-maneuvering their orbits, while neutralizing smaller threats by employing collision shields.

Ever since the first satellite was sent into space, certain unintended consequences have threatened to derail man’s exploration of the cosmos. The most prominent among these is the issue of space debris. New satellites that are launched must factor space debris into their trajectories to prevent any tragic mishaps. These tiny particles move at extremely high speeds—orders of magnitude faster than even the fastest assault rifle bullets!

The increasing number of satellites being launched into space translates into a greater amount of space debris each and every year. Long-term missions, like the International Space Station (ISS), must continuously remain on the lookout before any disastrous collisions occur.

Now, let’s delve into the measures that have been implemented on the ISS and other satellites to tackle this serious problem.

Threat From The Space Debris

Space debris refers to tiny, solid masses, both man-made and natural, that remain near the Earth in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). They vary in size from a few micrometers to dozens of inches across.

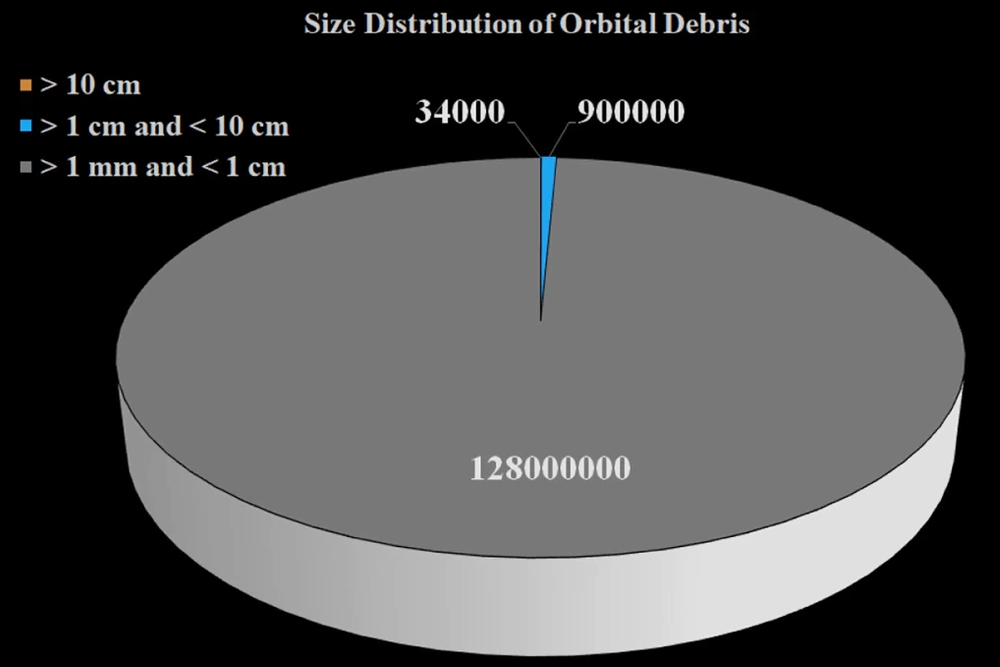

It is estimated that there are more than 100 million micrometer-sized pieces of debris orbiting the Earth, about 100 million pieces that are 1 mm or larger, 500,000 pieces the size of a marble (~1 cm), and 23,000 pieces the size of a softball. These pieces move at velocities of 15,700 mi/h (25266.7 km/h) and faster. For context, the muzzle velocity of an AK-47 is about 1,588 mi/h (2555.6 km/h) and the bullet diameter is 7.62 mm. Thus, it is clear that space debris poses an existential threat to satellites and the people inhabiting them.

In fact, in 1978, a NASA scientist, Donald J. Kessler, predicted that beyond a critical threshold of debris concentration in LEO, another collision would create a cascading effect, due to which exponentially more debris would be created, leading to the complete inoperability and availability of LEOs for orbiting spacecraft.

Also Read: Why Don’t Objects In Space Coalesce To Form A Big Chunk?

Space Debris Protection

It is impossible to protect against space debris with 100% efficiency, as there are hundreds of millions of these pieces in space. Most are too small to be tracked. NASA tracks objects that are 10 cm and larger, as their greater size enables their measurement and monitoring.

There are three threat levels, depending on the size and speed of the projectile. The protection measures range from orbital maneuvering for large objects (measuring more than 10 cm in size with a high threat potential) to collision shields that absorb the impact of smaller, less dangerous objects (measuring smaller than 1 cm).

Orbital Maneuvers

Orbital Maneuvering refers to a deliberate change in the trajectory of a satellite in order to avoid a collision. The simplest way of implementing this is to turn off the rocket boosters, if the satellite has them. For the ISS, a 30 mi  30 mi

30 mi  2.5 mi grid in space is created, with the spacecraft at the center. Objects that are 10 cm and larger are tracked and their trajectories are mapped. If the object happens to infiltrate the spatial grid of the ISS, a Debris Avoidance Maneuver is initiated.

2.5 mi grid in space is created, with the spacecraft at the center. Objects that are 10 cm and larger are tracked and their trajectories are mapped. If the object happens to infiltrate the spatial grid of the ISS, a Debris Avoidance Maneuver is initiated.

The probability of a collision is calculated. If the probability comes out to be more than 1/100,000 (>0.00001), then a maneuver is initiated, but only if it doesn’t jeopardize the mission objectives. If the probability comes out to be greater than 1/10,000 (>0.0001), then a maneuver is initiated, unless the threat to the crew is increased by the maneuver. The thrusters fire to impart sufficient kinetic energy to the space station to avoid the object in its near-space. Once the object has passed, re-entry maneuvers to the original orbit are initiated.

Whipple Shield

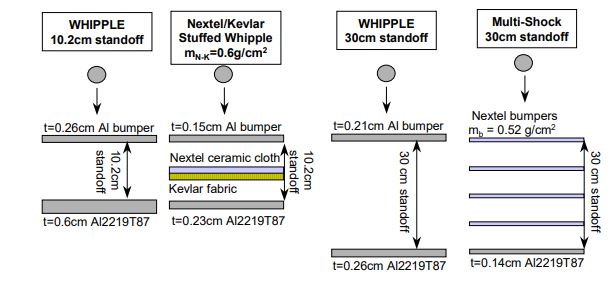

As the name suggests, a Whipple Shield is a physical barrier that protects against debris collisions with an object that is 1 cm or less in size. The shield bears the name of its inventor, Fred Whipple. It’s a two-stage protection system. The first is a bumper shield made of an Aluminum alloy that is 0.26 cm thick and exposed to space. It absorbs the bulk of any collision, which results in the breakage of the object into even smaller pieces.

The second stage is the spacecraft wall itself, which is designed to withstand any collision from the significantly weakened particles. There is also some space between the bumper shield and the spacecraft wall, called the standoff distance, which is 10.2 cm.

Stuffed Whipple Shield

This is a simple upgrade from the previous shield design, where a stuffing layer is introduced between the outermost layer and the innermost spacecraft wall. The outermost bumper is a 0.15 cm thick layer of Aluminum alloy. The standoff distance between the outermost bumper and the stuffing is 5.1 cm.

The stuffing is composed of two layers: A ceramic layer facing the outermost shield, followed by a polymer of suitable tensile properties, such as Kevlar. The stuffing layer is followed by the spacecraft wall, again separated by 5.1 cm. The presence of two layers before the spacecraft wall significantly decreases the risk of contact with the spacecraft itself, which is the ideal scenario.

Mesh Whipple Shield

As the name suggests, the outermost layer of this design consists of Aluminum mesh (very fine crisscrossing fibers of Aluminum), which absorbs the initial impact and breaks the debris into finer particles, which are then stopped by the stuffing layer behind.

Also Read: Is There A Way To Clean Up All The Space Junk?

A Final Word

Debris protection consists of a multi-stage system designed to cater to objects according to their damage potential. The most suitable course of action for large particles (>10 cm) is orbital maneuvering. For mid-sized particles, the course of action depends on their detectability.

If they are detected sufficiently early, then an orbital maneuver is initiated, depending on the probability of collision and fulfillment of the mission objectives. If they are not detected, then they are too small to cause a fatal threat to the spacecraft, so collision shields of varying structures and designs are employed, depending on the region that they protect and their probability of experiencing a collision in orbit.

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- ARES | Shield Development | Basic Concepts. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- Space Debris and Human Spacecraft - NASA. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- Pai, A., Divakaran, R., Anand, S., & Shenoy, S. B. (2021, July 20). Advances in the Whipple Shield Design and Development:. Journal of Dynamic Behavior of Materials. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- (2009) Handbook for Designing MMOD Protection. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration