Table of Contents (click to expand)

A 2015 study found that dogs in the study expressed a greater “want” for a familiar person they knew, rather than a familiar dog. It appears that dogs recognize us and our scent! Reasons for this range from selective breeding to social learning.

“It’s just the most amazing thing to love a dog, isn’t it? It makes our relationships with people seem as boring as a bowl of oatmeal.”

– John Grogan

The human relationship with dogs evolved as early as 32,000 years ago. It might be one of the longest and most successful inter-species relationships we’ve ever had. They’re our best friends and confidantes. When we go home after a long day of work, they give us a slobbery and drool-filled greeting, no matter what! Sometimes, their tails even wag at velocities that rival the blades of a helicopter.

However, as you see your dog bouncing around, a glaring question creeps in from the crevices of your brain: “Is my dog actually happy to see me… or are they just hungry?”

This question is absolutely fair, and leads us into the exploration of a larger theme. Do our dogs actually know us, recognize us, and love us?

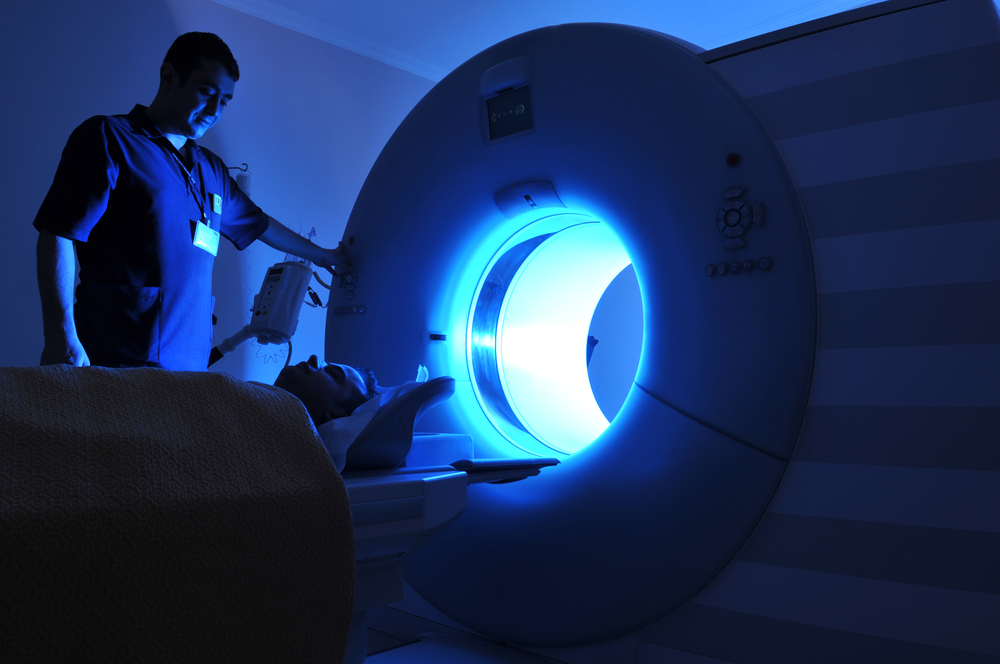

Turns out, one study aimed to answer exactly that. Twelve dogs were trained to sit unrestrained and unsedated in an fMRI machine.

An fMRI machine detects blood flow into the brain. The machine is often used to measure brain activity, especially for behavioral studies. It helps determine which parts of the brain are activated when engaging in specific or desired behaviors.

The dogs in this study were exposed to 5 scents while in the machine. Each dog was allowed to pick up the scent of a familiar person, an unfamiliar person, a familiar dog, an unfamiliar dog, as well as their own scent. Before explaining the results, it’s important to find out why scent or smell was chosen as the primary stimulus in this study.

Why Scent?

Dogs’ noses are like supercomputers. They have more than 100 million sensory receptor sites on their nose alone! Dogs have been known to sniff out cancer in patients with no symptoms and detect/unearth hidden weapons or missiles. Dogs can even sniff out their owners’ emotions.

However, a dog’s nose isn’t just capable of excellent smell detection. It’s how they primarily perceive the world and their surroundings. For any researchers designing a canine-related experiment, a dog’s sense of scent is crucial.

The premise for the study was simple: will the dogs respond better to the scent of a familiar human or to the scent of a familiar dog?

Also Read: Why Do Dogs Have Such A Great Sense Of Smell?

What Did They Discover?

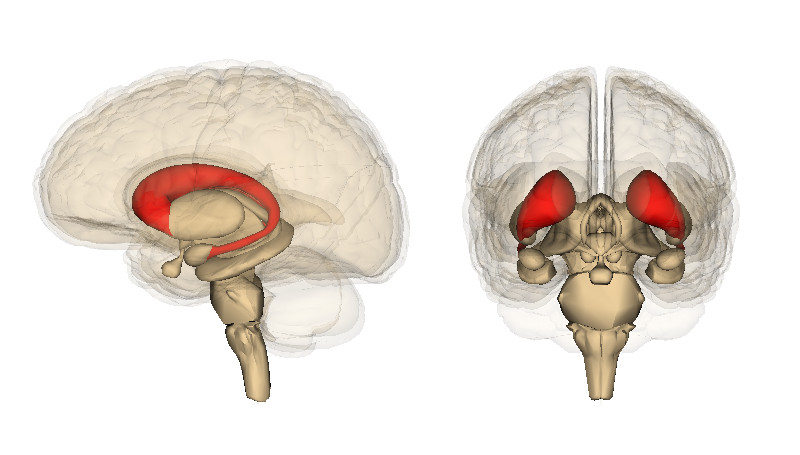

Of the 5 scents presented to the dog, the familiar human and dog scents caused the caudate nuclei of the dogs’ brains to glow with activity.

The caudate nuclei—one in each hemisphere of the brain—are located near the thalamus. The caudate nuclei have been well-documented to participate in neural systems responsible for generating responses related to learning, memory, reward, motivation, emotion, and romantic interaction.

Interestingly enough, the region was most engaged when the dog was exposed to the scent of a familiar human, not a familiar dog. This meant that the dogs in the study expressed a greater “want” for a familiar person they knew, rather than for a familiar dog!

It’s easy to chalk this up to feeding patterns, but this assumption was easily squashed, as the humans chosen for the experiment only had to meet one parameter: they lived in the same house as the dog or frequently interacted with the dog.

In fact, most of the humans whose scents were chosen engaged with the dog primarily in play, rather than feeding! The “want” for a familiar person was generated independently of any expectation for food or reward.

So, Why Do Dogs Like Us So Much?

There are two schools of thought here. Selective breeding has been explored as a possible explanation as to why dogs prefer humans over members of their own species.

After all, it is strange for an animal to prefer inter-species relations over intra-species ones. Selective breeding could explain that dogs prefer humans because the trait was specifically something they were bred to demonstrate.

This is a tempting explanation, and can conveniently tie up some loose ends for us. However, the dogs used in the study were not bred specifically to prefer human bonds. In fact, most were the result of accidental breeding, rather than purposeful breeding.

The second explanation involves the consideration of social environments. Areas of the brain that lit up in the fMRI were regions associated with familiarity, learning, memory and reward. These are all classical cognitive states associated with a nurturing environment. It is possible that the scent of a familiar human evokes an association with the memories of the nurturing environments in which the puppies were raised.

The human-canine bond is a hard one to explain. An explanation that incorporates both selective breeding and social environment is feasible, but it may be something else entirely. More concrete research into the matter is required.

Also Read: How Do Dogs Sense Human Emotions?

Conclusion

It’s true what they say… it’s hard to imagine a life without a dog once we get one. Apart from companionship, they keep us fit and on our toes. They also help us in uncertain times.

It is surprising to find that dogs prefer the company of the people who raise and spend time with them. This preference for inter-species relations over intra-species relationships remains a feature specific to domesticated animals. This trait seems to be particularly evident in dogs.

Basically, the next time your dog greets you with a wagging tail and a wiggling body, don’t get suspicious. They aren’t just fishing for food; they genuinely love you!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- (2021) Neuroanatomy, Nucleus Caudate - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. The National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Dilks, D. D., Cook, P., Weiller, S. K., Berns, H. P., Spivak, M., & Berns, G. S. (2015, August 4). Awake fMRI reveals a specialized region in dog temporal cortex for face processing. PeerJ. PeerJ.

- Fisher, H. E., Aron, A., & Brown, L. L. (2006, November 13). Romantic love: a mammalian brain system for mate choice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- Berns, G. S., Brooks, A. M., & Spivak, M. (2012, May 11). Functional MRI in Awake Unrestrained Dogs. (S. C. F. Neuhauss, Ed.), PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science (PLoS).