Woodpeckers have several adaptations that allow it to relentlessly peck at wood. From its tiny brain encased in a special skull and its long, curling-around-the-brain tongue, to its anatomy and pecking posture, every adaptation works to keep the woodpecker safe from concussions.

How much wood would a woodpecker peck if a woodpecker could peck wood without getting a headache?

Belonging to the Picidae family, woodpeckers have aptly and simply been named after the thing they love to do most—peck wood. If you’re a birder, you’ll catch these arboreal dwellers vertically clawed on a tree’s side, jamming their beaks into the bark at seemingly impossible speeds.

If you were to smash your face against a tree hundreds of times per minute, your brain would jiggle its way into some serious damage.

So, how are these birds managing all this high-speed pecking? Or do they simply carry on with a parade of concussions?

Why Does A Woodpecker Peck Wood?

A woodpecker’s diet consists of insects (eggs and larvae included), small worms and other types of invertebrates. Many of these wiggly creatures live inside tree trunks, so to access their meal, woodpeckers need to get through the tough outer parts of the wood.

Shelter is also a top priority for birds. Woodpeckers create cavities in trees in which they make their nests. Interestingly enough, these cavities aren’t made and then abandoned. After the woodpecker leaves its nest, other birds who can’t make their own nests, such as bluebirds, wrens and swallows, use the empty hole and fill it with life.

Woodpeckers occasionally hammer at something that isn’t wood, but there’s a completely logical explanation for this.

“Drumming” is when a woodpecker will pound on a resonant object (such as metal) to create noise. This might be annoying to listen to, but it is melody to the ears of a woodpecker’s mate.

Also Read: Why Don’t Birds Fall Off Branches When They Sleep?

High-speed Pecking, But Exactly How Fast?

When a skull is designed in a way that can absorb a massive 1,000 Gs worth of force (1,200 times the force of gravity), it might as well be called a sponge!

An average male hairy woodpecker can strike its target at an astounding 2o pecks per second! At this rate of hammering an object, any other animal’s brain would become a soupy mess, so how do woodpeckers avoid this?

The ‘Helmet’ Protecting The Woodpecker

Scientists began by investigating the skull of woodpeckers. Was it an efficient shock absorber? Was it made of a different type of bone? A recent study found that a woodpecker’s skull is, counter-intuitively, not a shock absorber. In fact, the bird uses its head more like a hammer than a protective casing for its brain. A skull that absorbs the repeated shock would also prevent the bird from pecking.

The bird also has something else going for it—its size. A human brain is larger, which means that the surface area in contact with the skull is larger. Compared to us, a woodpecker’s brain is quite pea-sized. Even if the brain jostles around a bit in the skull, it won’t significantly impact the bird.

However, another structure in the skull provides the brain with essential stability.

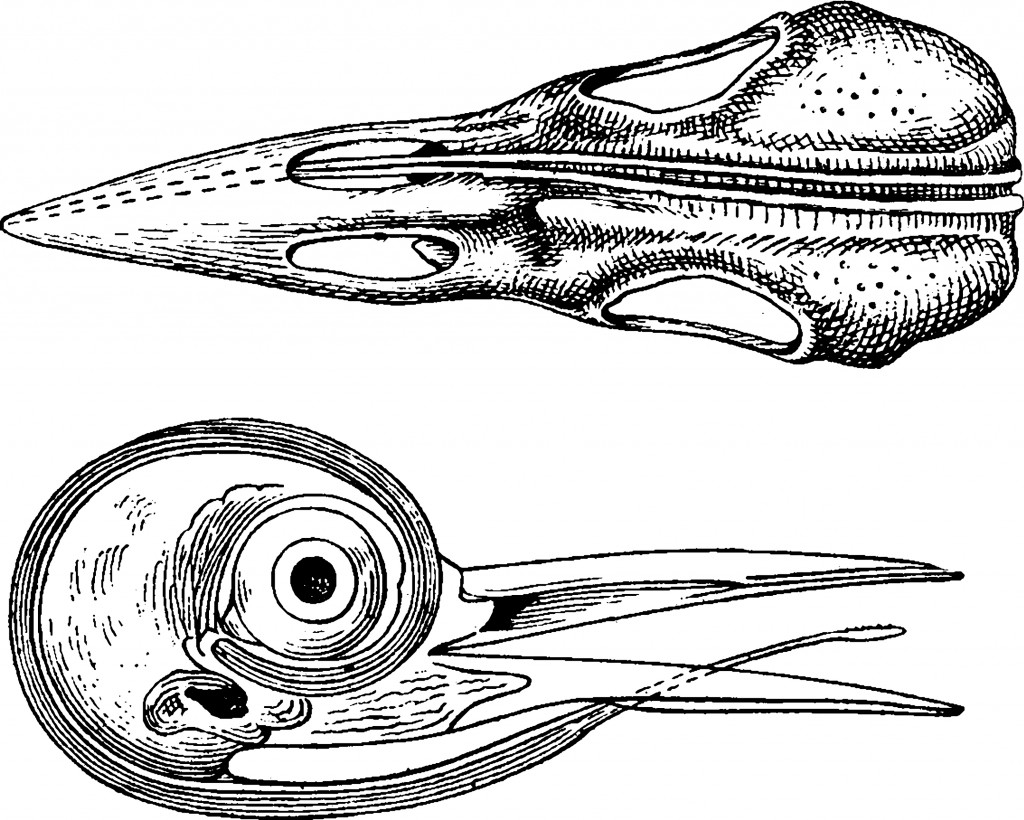

The hyoid bone is a horseshoe-shaped bone present in the floor of the mouth that keeps the tongue in place. When it comes to woodpeckers, the hyoid bone is not only present in their beak, but extends inwards until it forms a loop that encompasses the whole brain.

Like a seatbelt, it holds the brain safe and secure, even as the head goes for a wild pecking ride.

Additionally, the orientation of the brain, neck muscles that bear a good amount of strength, and a tightly packed skull with no extra space, all work to the bird’s advantage. They even have an in-built protective shield (bristled nostril feathers) to protect themselves from breathing in the tiny chips of wood flying off in their direction.

Also Read: How Do Birds Break Down Their Food If They Don’t Have Any Teeth?

The Woodpecker’s Beak

Perhaps the bird’s most prized asset is its beak. Shaped like a chisel, it cuts through the wood, rather than stopping on contact. This avoids any shock waves that would come from doing the latter.

Scientist have also found that the tissue layer covering the woodpecker’s upper beak is longer than the layer covering the lower beak, while the bony structure of the lower beak was longer than the upper. This mismatch, scientists believe, also allows energy to be directed through the lower beak and away from the brain casing.

Posture During Pecking

It’s not just the uniquely designed skull or beak that gives the woodpecker the license to hammer without a headache. Have you ever seen the position a woodpecker assumes when it’s pecking?

Their feet, with two toes in the front and two in the back (unlike other birds with three in the front and one in the back), allow them to remain vertical while clinging to the tree trunk. This further reduces the impact to the body as a whole.

The Unique Fine-tuned Iron Tongue

Given that all of their anatomy and morphology enable them to seamlessly drill holes, there’s nothing left for the bird to do other than stick out its tongue (one-third of its body length), and slurp up the treasured sap and insects within the tree.

But where do they store such a long tongue? Surely the beak can’t hold all of it!

The tongue is anchored in the head, wrapping around the back of their brains. Not only does this solve the storage issue, but it also gives the brain a cushion-like support.

Closing Thoughts

Just like the mountainous rams who wage rutting battles with their heads, the structure of the skull of an animal plays an important role in the protection of its brain. The anatomical features unique to the woodpecker work ingeniously to give it the liberty to head-bang on any object they choose.

This adaptation in woodpeckers could work as a model of biomimicry, wherein people learn how nature works its wonders and tries to simulate the same ability using similar techniques. Helmets engineered to mimic the intricacies of the woodpecker’s skull arrangement could potentially aid in preventing head and brain injuries of athletes playing various high-impact sports.

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Catalina-Allueva, P., & Martín, C. A. (2021, January 3). The role of woodpeckers (family: Picidae) as ecosystem engineers in urban parks: a case study in the city of Madrid (Spain). Urban Ecosystems. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Baum, P. (2020). Woodpecker Drumming Analysis. Unpublished.

- (PDF) Drumming and tapping by Red-bellied Woodpeckers. ResearchGate

- Why Don't Woodpeckers Get Concussions? - MTPR. mtpublicradio.org

- September 2019 | Biomechanics in the Wild - Notre Dame Sites. The University of Notre Dame du Lac

- Woodpeckers - K-State Extension Wildlife Management. Kansas State University

- Van Wassenbergh, S., Ortlieb, E. J., Mielke, M., Böhmer, C., Shadwick, R. E., & Abourachid, A. (2022, July). Woodpeckers minimize cranial absorption of shocks. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- Bock, W. J. (1999, March). Functional and evolutionary morphology of woodpeckers. Ostrich. Informa UK Limited.

- Jung, J.-Y., Naleway, S. E., Yaraghi, N. A., Herrera, S., Sherman, V. R., Bushong, E. A., … McKittrick, J. (2016, June). Structural analysis of the tongue and hyoid apparatus in a woodpecker. Acta Biomaterialia. Elsevier BV.