Table of Contents (click to expand)

Birds balance while sleeping by locking their talons onto the branch. They also sleep with one brain hemisphere awake, and have a balancing organ in their hip

Some of life’s simplest mysteries can prove the hardest to solve. One such mystery is how a bird sleeps, especially while it’s perched so precariously on a branch? Or for that matter, how do birds remain perched in the armpit of a giraffe like the yellow-billed oxpecker, or hang upside down on a tree branch for a snooze like a parrot?

How Do Birds Sleep?

Although birds do sleep, they don’t sleep quite like us humans.

First of all, they sleep for a lot less time than we do. Humans, and many mammals overall, have longer sleep cycles compared to birds. REM sleep, the part of the sleep cycle when we are in the deepest sleep (and also when we dream), lasts for several minutes in mammals, but hardly 10 seconds in birds. Birds sleep by basically taking mini-naps.

Do Birds Sleep With One Eye Open?

Birds can also modulate how intensely they sleep. They can keep one hemisphere of their brain awake, and you may notice this when the bird has one eye open. The eye that is open is connected to the opposite hemisphere. So, if the right eye is open, the left hemisphere of the brain is awake, and vice versa. This light and flexible style sleeping allows birds to flee from a predator on a moment’s notice, even when they’re in the middle of a nap.

Furthermore, not all birds roost atop branches. Birds like the ostrich, for example, the largest bird on the planet, wouldn’t be able to climb a tree if its life depended on it. Most flightless birds sleep on the ground, hidden among foliage, or with their head seemingly “in the sand”. Some other birds sleep standing on one leg in bodies of shallow water, like flamingos.

Also Read: How Do Birds Sleep During Migration?

Clutching The Branch – Automatic Perching Mechanism

To fall asleep, a bird’s body goes through a series of physiological changes. One of these changes is that the muscles lose their stiffness. This happens as a result of reduced brain control of muscle movement, along with various other physiological changes.

To stand perfectly balanced on a branch while the muscles become limp isn’t easy. Anyone who has tried to sleep standing on a train would know this. Birds manage to combat this limpness by locking their legs.

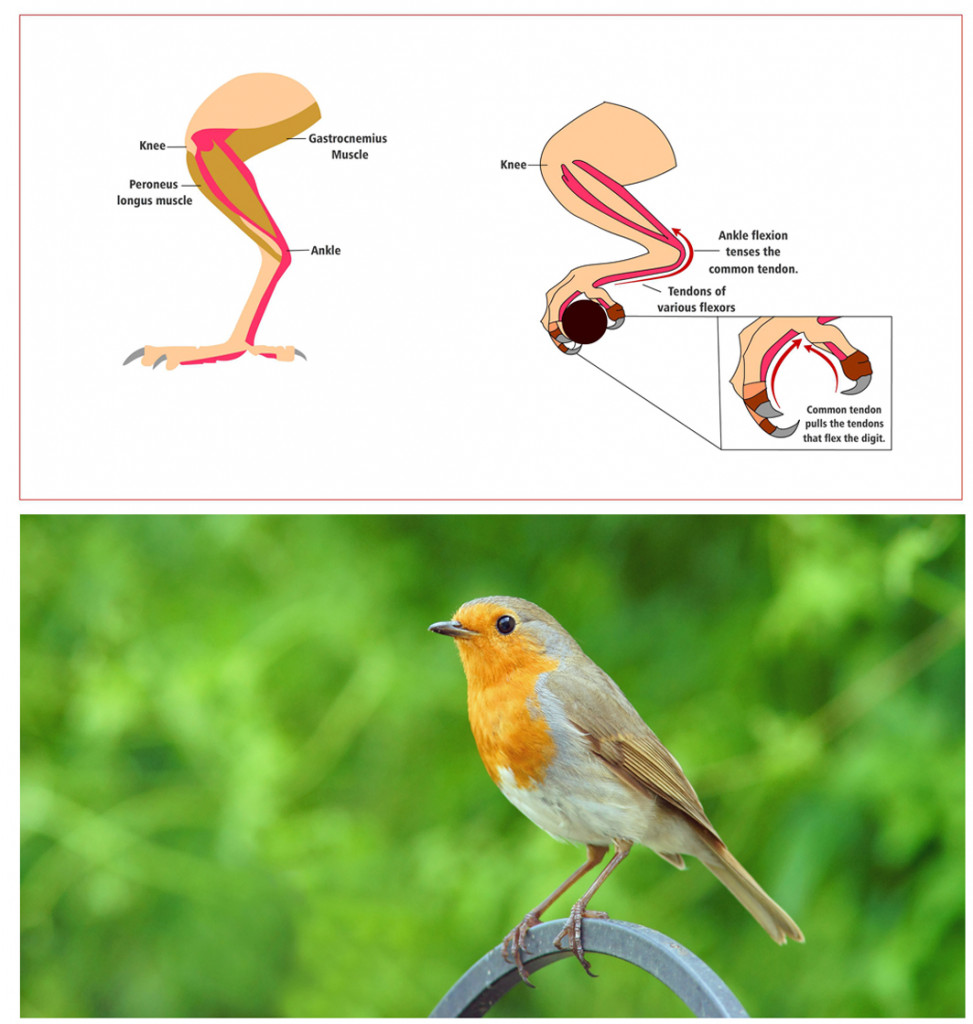

When a bird squats, its talons automatically bend and clutch tightly to the branch, for example. Until the leg is straightened, the talons will not release. The lock occurs because of how the flexor tendons, the tissue that connects to muscles and helps the limb bend, are placed in the legs. As the knee and ankle of the bird bend, the flexor tendon stretches, thus bending the talons.

The locking mechanism also happens because the tissue covering the tendon has a rough surface, although it is smooth in most other animals. The rough surface creates friction between the tendon and the sheath around it, which helps to lock the leg in place.

This so-called ‘automatic perching mechanism’ is a feature in most birds, allowing them to clutch to a branch without worrying about losing their grip and falling off. It isn’t only birds perched upright that benefit from this nifty trait. Parrots actually sleep hanging upside-down!

The locking mechanism comes in handy in other ways too. For predatory birds, for example, being able to firmly clutch their prey while flying to a safe place to feed is the difference between a full belly and starvation. It also helps birds to climb, swim, wade through water, and hang.

Exception To The Automatic Perching Mechanism

Dozens of papers found such a mechanism in different avian species, and the case seemed shut, but a paper published in 2012 found that sleeping European Starlings don’t use the locking mechanism when they sleep. The researchers observed that the birds bent their knees only slightly, not enough for the locking mechanism to kick into action.

The toes, as a result, were largely unbent, and the bird balanced on the central pad of its feet while it slept. Additionally, they found that when the birds were anesthetized, they could not balance on the branch.

These results imply that there is more to how a bird balances as it sleeps than a simple brute-force grasp.

Also Read: Why Do Bats Hang Upside Down While They Sleep?

How Does A Bird Balance On A Branch?

Without the passive and automatic perching mechanism, the muscles of birds would need to have some stiffness. There is some evidence to suggest that birds can, when called for, not go completely limp. Research on birds like geese, flamingos, and frigates show that birds can maintain some muscle stiffness, or tone, when required. This might have something to do with birds being able to keep one brain hemisphere awake, and the fact that they have short REM cycles. A minimal amount of muscle tone is required for the bird to balance, sometimes even on a single leg.

However, besides muscle tone, there might be several other systems at play to keep a bird perched and stable while asleep. There is little conclusive research as to how a bird balances in its sleep and which neural and physiological mechanisms operate this behavior.

One interesting discovery found that birds, especially those that perch, have a unique balancing organ in their hip, close to their buttocks. Called the lumbosacral organ, in scientific jargon, this organ might allow birds to keep their balance, in addition to the vestibular system in their heads. Therefore, if a bird tucks its head away when it retires, the hip balancing act comes into play. This is purely conjecture though, and there isn’t any conclusive evidence on the matter… yet.

Also Read: Why Do Flamingos Stand On One Leg?

Conclusion

Studying bird sleep has its own challenges. For one, birds are a diverse and eclectic bunch. They’re bodies, physiologies, and behaviors can be vastly different depending on which species, genera or family one studies. Sleep cycles differ just as widely. Comparing how an ostrich sleeps to how a sparrow or a flamingo sleep would be foolish, and likely uninformative.

Even when we consider the automatic perching mechanism, the shape of a bird’s foot comes into play. Bird feet are adapted to different purposes, so the way they stand and the movement of their feet might also be different.

We may not know the whole story yet, but there is no denying how remarkable it is that birds manage this balancing act every day!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- GALTON, P. M., & SHEPHERD, J. D. (2012, April). Experimental Analysis of Perching in the European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris: Passeriformes; Passeres), and the Automatic Perching Mechanism of Birds. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological Genetics and Physiology. Wiley.

- Quinn, T. H., & Baumel, J. J. (1990, July). The digital tendon locking mechanism of the avian foot (Aves). Zoomorphology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Quinn, T. H., & Baumel, J. J. (1990, July). The digital tendon locking mechanism of the avian foot (Aves). Zoomorphology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Rattenborg, N. C. (2017, February 6). Sleeping on the wing. Interface Focus. The Royal Society.

- Chang, Y.-H., & Ting, L. H. (2017, May). Mechanical evidence that flamingos can support their body on one leg with little active muscular force. Biology Letters. The Royal Society.