Table of Contents (click to expand)

A few early birds used to have teeth, but a mutation eventually inactivated the genes involved in developing teeth. Evolution selected for this mutation, leading to toothless birds. There are several theories as to why evolution preferred toothless birds over those with a set of pearly whites.

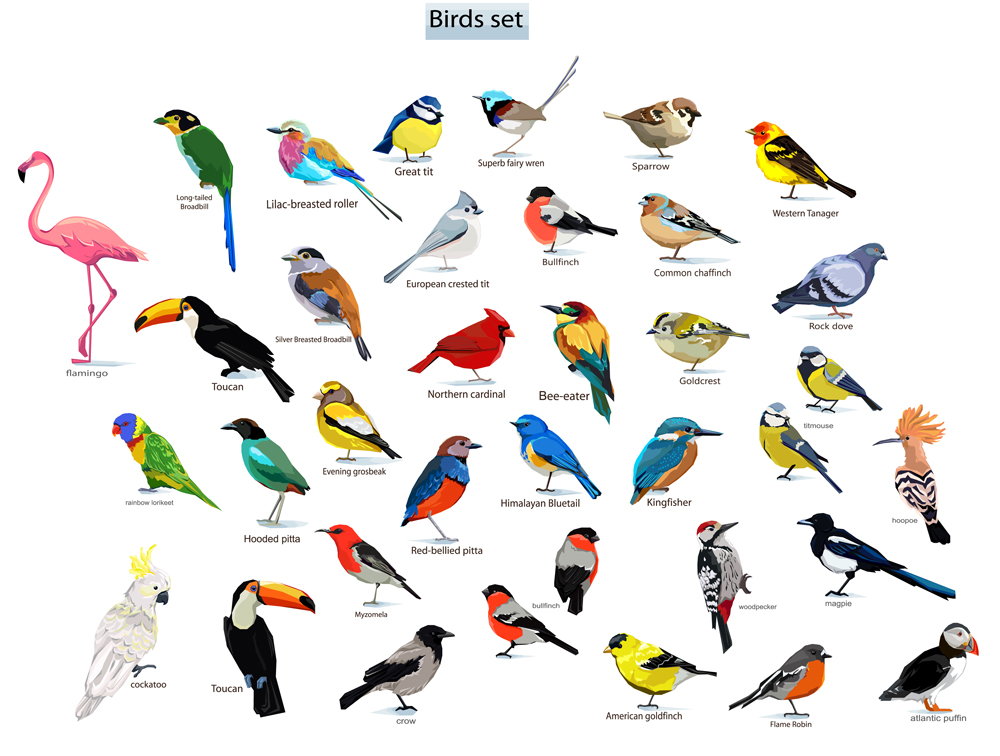

A bird’s beak is a truly fascinating tool. It can be pointed or blunt, bright or dull, small or comically large, yet they all serve their owner’s particular purpose. Be it ripping apart flesh, cracking tough nuts, or delicately sipping nectar from flowers, with the right beak, nothing is impossible… except chewing food, as all modern birds’ beaks are toothless!

Why don’t birds have teeth? And did they ever have teeth?

Have Birds Always Been Toothless?

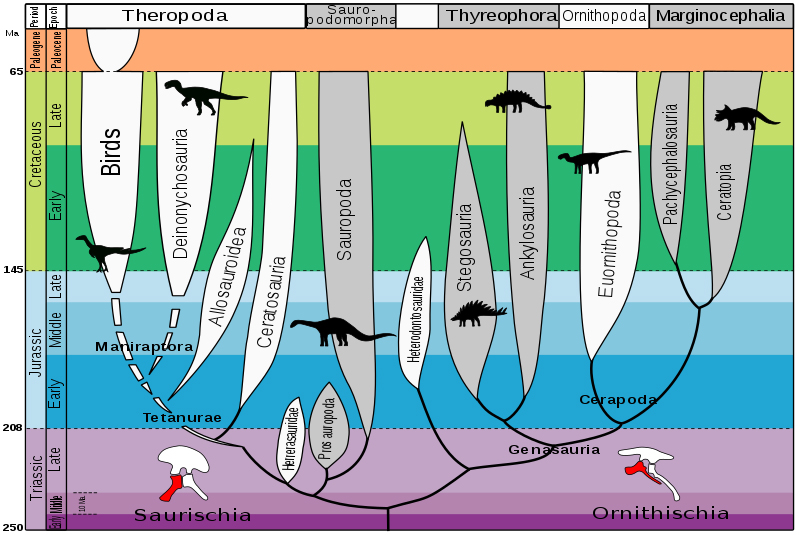

Modern birds have been evolutionarily linked back to theropod dinosaurs, a class of dangerous, hungry dinosaurs with pointy teeth. Yet somehow, the T-Rex and velociraptor gradually evolved into pigeons, ducks, and hummingbirds.

Birds Which Had Teeth

The last common ancestor of birds and dinosaurs to have a full set of teeth was Archaeopteryx lithographica, which lived some 150 million years ago. However, the fossil records of evolutionarily early birds, such as Ichthyornis dispar, which existed in the late Cretaceous period (93–65 million years ago), still show the presence of teeth. It had a partial beak in front of its mouth and teeth in the back.

The Ichthyornis dispar represents an “in-between stage”, proving that the development of the beak happened around the same time as the loss of teeth.

This indicates that birds lost their teeth roughly around 100 million years ago, but the why and the how have remained a mystery until quite recently.

Also Read: Are Birds Really Reptiles?

How Did Birds Lose Their Teeth?

A research team led by biologists from UC Riverside and Montclair State University uncovered that 48 bird species shared mutations that inactivated both enamel-related and dentin-related genes. Enamel is the hard tissue that covers the teeth, while dentin is the calcified stuff underneath it.

This discovery meant that, at some point during evolution, a common ancestor of birds lost the ability to form teeth, giving rise to the toothless birds we see today.

Interestingly, in 2006, scientists from the University of Manchester and the University of Wisconsin were able to turn back time by giving chicks teeth! They overcame the mutations preventing teeth formation by manipulating a chicken’s genes so that it could actually grow teeth. This cemented the theory that tooth loss in birds occurred due to the inactivation of certain genes over the long course of evolution.

Also Read: Do Animals Need To Brush Their Teeth Like Humans?

Why Did Birds Lose Their Teeth?

This question has confounded many of the same researchers for years. “Why would an entire major group of animals lose their teeth?” asked Stephen Brusatte, a paleontologist who has extensively studied the overlap between dinosaurs and birds.

Easier To Fly

A popular theory suggests that toothlessness in modern birds was an adaptation to make them lighter for flight, but this theory is scientifically weak, as flying mammals such as bats also have teeth.

Dietary Changes

An alternative theory was that tooth loss was connected to dietary changes.

At the end of the Mesozoic era, primitive birds with teeth disappeared in favor of those with beaks. Possibly, beaks were simply better for eating bird food than teeth and had therefore prevailed. However, this theory doesn’t make sense when you consider how well-adapted teeth are to various dietary habits. The fact that some dinosaurs with completely different meat-eating habits also traded teeth for beaks is another chink in this theory’s armor.

Reduction In Incubation Period

A third and relatively new hypothesis has been put forth by researchers from the University of Bonn, Germany. They suggested that the loss of teeth reduced the incubation time of bird eggs and was therefore favored during evolution.

Unlike other egg-laying creatures, e.g., reptiles and fish, birds lay a relatively small number of large eggs that require a short amount of time to hatch (11-85 days on average). This short incubation period drastically increases their chances of survival. It limits the amount of time the eggs are vulnerable to the environment and to predators, thus resulting in many fit, young birds.

In comparison, research showed that their ancestors—the non-avian dinosaurs—laid eggs that took three to six months to hatch. This long incubation period has been attributed to slow dental formation. Developing teeth is complex and accounts for around 60% of the egg incubation time. Basically, the embryos had to wait inside the egg until their teeth had formed and only then could they hatch.

Faster incubation must have aided early birds and some dinosaurs who made open nests, as opposed to burying their eggs. As these animals evolved, the time-consuming teeth were sacrificed to allow for faster embryo growth. Shortening the incubation period meant that the likelihood of losing the eggs or the incubating parent to natural disasters, disease or predators was lessened.

Although this theory seems to be the best one yet, researchers agree that it does not explain toothlessness in turtles, which still have a long incubation period. Perhaps we’ll never know for sure why birds lost their teeth, but one the one thing that can’t be debated is that they weren’t always like this!

Also Read: Why Do Flightless Birds Go Extinct So Often?

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Davit-Béal, T., Tucker, A. S., & Sire, J.-Y. (2009, April). Loss of teeth and enamel in tetrapods: fossil record, genetic data and morphological adaptations. Journal of Anatomy. Wiley.

- Yang, T.-R., & Sander, P. M. (2018, May). The origin of the bird's beak: new insights from dinosaur incubation periods. Biology Letters. The Royal Society.

- Erickson, G. M., Zelenitsky, D. K., Kay, D. I., & Norell, M. A. (2017, January 3). Dinosaur incubation periods directly determined from growth-line counts in embryonic teeth show reptilian-grade development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.