Table of Contents (click to expand)

Not all plastics are equally harmful to the environment. Thermoset plastic are strong and more durable, which makes them harder to recycle, as opposed to slimy thermoplastics. Furthermore, there is a Resin Identification Code (RIC) that grades which plastics can be recycled and how. Lastly, some plastics have chemicals, such as chlorines, that can be toxic to their surrounding environment.

In 1907, Leo Baekeland, a Belgian chemist, beat chemist James Swinburne to a patent office in Scotland by the mere margin of a day. There, Baekeland patented a material known as Bakelite. Bakelite was the first fully synthetic plastic in the world. It was a worthy predecessor to the types of plastic we use today. From food containers and baby bottles to electronic chip carriers, plastic is as ever-present as sunlight. Today, the market for plastic has never been larger. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the logistical burden of the medical industry was almost single-handedly borne by synthetic polymers and common plastics. Millions of plastic gloves and masks were used every day.

Of course, plastic isn’t only evil in the world, but with so much of it around, what the heck do we do with all this plastic once we’re done with it?

What Is Plastic?

To understand what happens to plastic as garbage, we need to know what plastic is, chemically speaking.

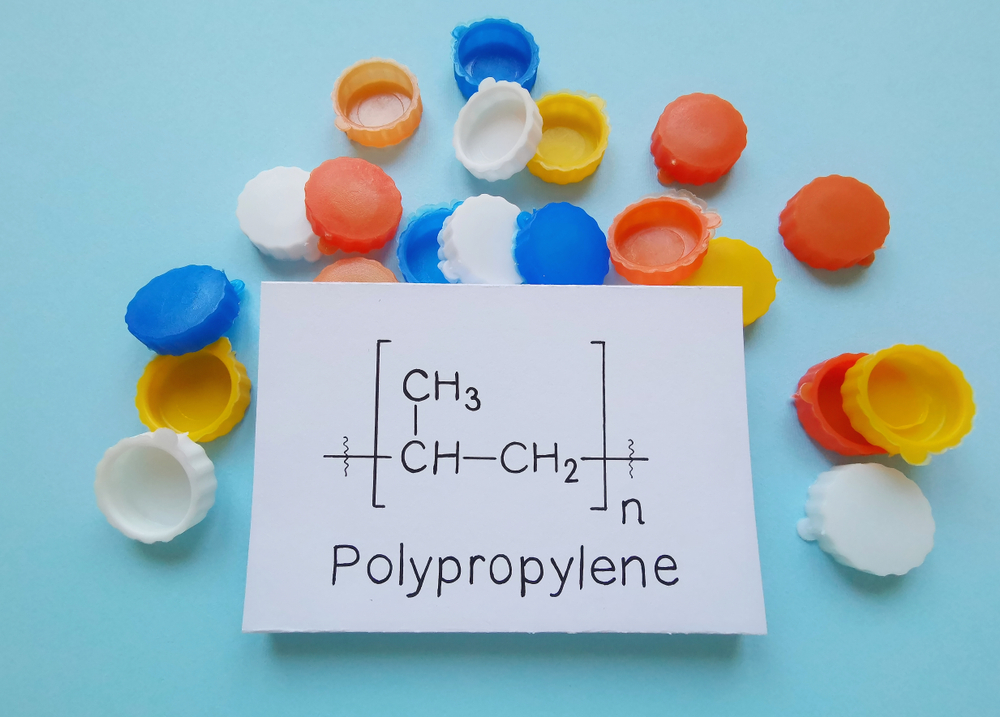

Plastic is a polymer that, in the simplest of terms, is composed of small chemical blocks—monomers—attached to each other to make a large molecule, the polymer. The monomers form covalent bonds with other monomers. Monomers covalently link together to form chains, which together form a polymer.

It’s easier to think of a monomer as a brick. Multiple bricks are sequentially laid together to build a house. The house is a polymer. However, not all plastics are the same type of polymer. Plastics come in two types; thermoset plastics and thermoplastics. The difference lies in their chemical and physical properties.

Thermoset plastics are manufactured using processes called liquid molding processes. Polymers and other agents are heated to a liquid state, and as the mixture cools in the mold, it forms a thermoset plastic. This process encourages a chemical reaction known as cross-linkage. When the polymers in the mixture cross-link together, it prevents them from succumbing to the effects of heat. Thermosets such as polyester, polyimides, and polyurethane are therefore perfect for high-heat environments. The cross-links in thermoset plastics are also the reason they are impossible to recycle. Thermoplastics, on the other hand, are susceptible to the effects of heat and melt when exposed to high heat after the curing process. This makes them a bit easier to recycle. Polyethene is a good example of a thermoplastic.

What Happens To All The Plastic Once We’re Done With It?

One word: Recycled

Actually, it’s a bit more complicated than that. The problem with plastic is that we can’t transform it into another substance. Technically, it is possible to recycle plastics into fuel or oil, but this process results in the emission of toxic pollutants—a no-win situation.

Most plastics are not biodegradable. They break down into smaller pieces, but not simpler substances (i.e., organic or biological materials). These smaller pieces of plastic are called microplastics.

To prevent plastics from turning into microplastics, the ideal solution is to recycle them. However, many weird problems come up when we try scaling up plastic recycling.

Plastics and objects made of plastic are each assigned a Resin Identification Code (RIC). This code helps us identify the type of plastic used to make an object. Based on this code, each plastic item can belong to 1 of 7 classes. RIC Classes 1 (things made of PETE/PET) and 2 (things made of HDPE) can be recycled. RIC Classes 3-7 can possibly be recycled (depending on where you live).

The headache doesn’t end there. Specific cases like two-layered objects (your coffee cup) make plastic recycling harder. Plastic fused to another material (paper) cannot be recycled. The two materials need to be separated and then processed.

Additionally, some plastic items can only be recycled a maximum of 2 or 3 times, because every time plastic is recycled, the monomeric chains that make up the plastic reduce in length. This directly affects the quality and strength of the resultant plastic.

Weirdly enough, most recycled plastic is reinforced with new or “virgin” plastic to make up for the loss of quality incurred during recycling. This goes directly against the very point of recycling—to use less of it. One may rightfully question if this should count as recycling at all.

Also Read: Why Are We So Dependent On Plastic?

So, Are All Types Of Plastic Bad For The Environment?

Not really.

RIC Class 1 and 2 plastics are the most extensively recycled plastics. Hence, they’re also less likely to contribute to the production of microplastics. Generally, they are also used to make simple single-layered products, such as water bottles (100% PET).

In terms of harm done, they’re as innocent as plastics can get. Classes 3-6 are a bit trickier to judge, as the processes required to recycle them do exist, but depending on where you live, they’re not always recyclable.

Plus, for some plastics, such as PVCs or polystyrenes, multiple complex processes (pyrolysis, hydrolysis, heating, etc.) are required to successfully recycle them.

Dubiously, we must also be wary of Class 7 plastics. All plastics that fall into the Class 7 category of plastics meet one basic requirement: They do not fit anywhere else. If the object in question doesn’t find a place amongst the first 6 classes, it is simply dumped in class 7. It is a literal landfill of unidentifiable plastics. This makes all plastic items in Class 7 difficult to recycle, as not much is known about their composition.

Also Read: What Is Plastic Leaching And Why Is It Bad?

Conclusion

In the end, some types of plastics, like Polyvinyl chlorides and Polysterenes, are more dangerous than others. Many of the processes used in recycling PVCs attempt to remove the hazardously high levels of chlorine and additives added to it. In fact, the WHO has classified PVC as a carcinogen.

The real problem is the dangerously small amount of plastic being recycled at all. Worldwide, only 9% of plastic is actually recycled.

We need to figure out a better way to increase the scale and quantity of plastic recycling. Unless we figure that out, the type of plastic doesn’t really matter, as most of the plastic that is produced will eventually end up breaking up into microplastics, since they won’t be recycled in the first place.

To end on a lighter note, it’s not all doom and gloom. Chemists and engineers are working tirelessly to synthesize new-age bioplastics, which are synthesized from renewable and biodegradable raw materials like vegetable oil, yeast, or corn. Capable of biodegradability, bioplastics present a source of optimism for plastic management in the near future.

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Thompson, R. C., Moore, C. J., vom Saal, F. S., & Swan, S. H. (2009, July 27). Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- 7 Things You Didn't Know About Plastic (and Recycling). The National Geographic Society

- Converting Plastic Waste into Fuel - Science in the News. Harvard University

- Bioplastics - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. ScienceDirect

- The Truth About Bioplastics - State of the Planet. Columbia University

- The Age of Plastic: From Parkesine to pollution. The Science Museum

- What are microplastics? - NOAA's National Ocean Service. The National Ocean Service