Table of Contents (click to expand)

There are three primary reasons for why satellites are not sent straight up and out of the solar system: (1) doing so would require the satellite to cancel out its motion in the direction of Earth’s orbit, which would use a great deal of fuel; (2) most of the interesting stuff in the solar system lies in the plane of the solar system, so it makes more sense to send probes horizontally along that plane; and (3) a probe sent straight up and out of the solar system is unlikely to find anything significantly interesting.

I have a friend—one who is not much into space and science—who asked me once: the moon is on ‘top’ of us, right? Because we see it when we look above our heads. This belief is also supported by the fact that all satellites and spacecraft are launched vertically upwards because they must reach the moon or other celestial objects that are located ‘above’ us.

As much as I was impressed by his assumption (i.e. the moon and other celestial bodies being located ‘above’ us), which seems perfectly reasonable on the surface, I told him that this was not the case. All celestial bodies in our solar system lie on the same plane. In simple words, it means that our solar system is almost flat (ecliptic, more specifically).

That observation got me thinking: why don’t we send space probe upwards out of the solar system? Wouldn’t it make more sense to have these probes reach a certain height above the Earth where they could take better images from a “higher” vantage point?

Earth’s Orbital Velocity Is Huge!

First off, it’s important to note that Earth is moving in the ecliptic (i.e., plane of the solar system) at around 30 kilometers per second! This means that any object leaving the planet moves at a speed of “its own speed + Earth’s orbital speed”. For instance, when you throw a ball out of a moving train, the ball moves at the speed of the train plus the speed at which you threw it.

In order to send a space probe vertically upwards outside the plane of the solar system, you would first need to burn a great deal of fuel just to cancel out the satellite’s motion in the direction of Earth’s orbit. Only after that could you boost the probe in the vertical direction so that it flies vertically upwards, out of the ecliptic.

Also Read: What Is Escape Velocity?

Too Much Fuel

Going straight upwards out of the solar system would require the probe in question to burn a whole lot of fuel. The probe would have to therefore carry that load, which increases the mass of the satellite. Thus, from a logistical standpoint, it would be quite a task for the concerned space agency to accomplish. Needless to say, it would be an exceedingly expensive mission.

Nothing Much To Explore

You may already know that the solar system lies mostly in a plane. Most of the interesting stuff, or at least the stuff that we want to explore, lies in the plane of the solar system. So, it naturally makes more sense to send probes horizontally along the plane of the solar system.

If we do build and launch a probe that goes vertically upwards outside the solar system’s plane, it’s highly unlikely that it would find anything significantly interesting. However, if it kept going upward, it might eventually run into the Oort cloud.

That being said, we don’t know exactly where the Oort cloud begins and ends. Consider this: at its current speed (i.e., 1 million miles a day), Voyager 1 spacecraft probably won’t reach the Oort Cloud for about 300 years (Source).

However, it’s not like we’ve never sent any probe vertically upwards and out of the solar system.

Enter Ulysses!

Also Read: How Are Unmanned Space Probes Guided Through Space?

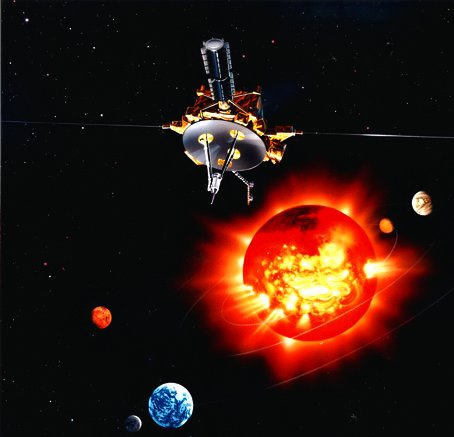

Ulysses – An Interesting Exception

Back in 1990, NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) launched a robotic space probe called Ulysses whose primary mission was to orbit the sun and study it at all latitudes.

In order to do that, Ulysses had to leave the plane of the solar system by changing its own orbital inclination. To do this, it first flew out to Jupiter in the usual in-plane way and subsequently used a gravity assist to rotate its orbital plane perpendicular to the solar system.

Not just Ulysses, but also Voyager 1 and 2 have their escape trajectories tilted about 35 degrees and 80 degrees, respectively, out of the ecliptic plane. This means that these space probes are moving along an inclined plane with respect to the solar system’s plane.

Also Read: Gravitational Slingshot: How Did Gravity Assist Voyager 1 &Amp; 2 In Escaping The Solar System?

How well do you understand the article above!