Table of Contents (click to expand)

Spandrels are byproducts of evolution. They arise due to the evolution of one trait, but this unintended trait may not have any function.

Gould and Lewontin defined a biological spandrel as a byproduct of evolutionary adaptation. Simply put, they’re like ‘leftovers’ of some other trait that evolved. This means that the spandrel isn’t an adaptation to anything in the environment. Instead, it is a secondary trait that arose from the development of another primary trait.

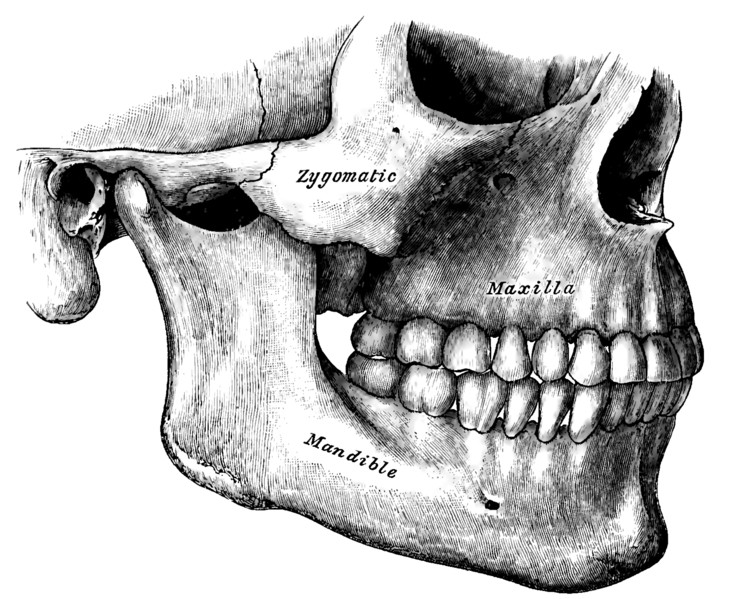

The easiest spandrel to visualize is the human chin. On hypothesis about why humans are the only animals that have a chin is that it is merely a byproduct of the growth of different parts of the jaw.

The jaw was an adaptation to the kind of food humans used to consume during our good old prehistoric days. The chin is a secondary trait that developed because of the first jaw adaptation. This secondary trait isn’t an adaptation to any specific environmental conditions.

The evolution of the chin, in isolation from the jaw’s evolution, would mean very little to the animal’s survival.

This proposal of a trait that served no adaptive purpose was a critique of the thought that every trait is an adaptation and has been selected for through natural selection.

Are Spandrals An Adaptation Or A By-product?

Adaptationists argue that every trait must have some evolutionary function or else natural selection wouldn’t have selected for the trait to persist. They argue that the environment weeding out the less fit individuals is the biggest pressure and driving force behind evolution, keeping only the functionally important traits around.

On the flip side, Gould and Lewontin argue for a more pluralist approach to evolution.

Pluralism in evolution refers to considering multiple factors that may have affected a trait. In popular science, natural selection is synonymous with evolution, but that isn’t the whole story. There are three other major mechanisms of (micro)evolution—genetic drift, mutations and gene flow. Pluralists argue that adaptationism often attributes a purpose to a trait because it must, not because the evidence leads to it.

Gould and Lewontin weren’t the first to start the debate between pluralism and adaptationism. The first rift began when the theory of evolution itself was being born, between Charles Darwin, and Alfred Russel Wallace and August Weissmann.

Darwin held a pluralistic view of evolution advocating other mechanisms of evolution also be considered along with natural selection. Wallace and Weissmann, on the other hand, took up the adaptationist mantle. Over the years, any other prominent evolutionists have helped to further shape and influence adaptationist and pluralist views. The debate between the two has reached a stalemate, with many having accepted the spandrels argument.

Also Read: Does (Natural) History Repeat Itself?

Why Do Spandrels Exist?

Adaptationism, according to Gould and Lewontin, not only showed an incomplete history of certain traits but could also lead to misleading and counterproductive results. If one looks at the human chin like an adaptationist, one would conclude that the chin evolved because humans found George Clooney-esque chins sexy.

Thus, people with chins found mates more often than those who didn’t. Subsequently, those humans who had sexier chins were more successful and therefore thrived. While chins can be a metric for attractiveness, this purpose of the chin came after its appearance in humans, argued Gould.

Gould referred to the something useless attaining a purpose as ‘exaptation’ of function.

Spandrels have a wonderful ability to co-opt certain traits that appear to modern scientists as a primary trait. Consider architectural spandrels. They are used to display complex imagery and art that serves to elevate the aesthetic value of the building.

Does that mean the architects created the spandrel solely to decorate? Obviously not. That sounds illogical. Gould argues a similar case for biological spandrels. Think of evolution as an architect putting a non-adaptive trait to use.

There are many other examples. The hollow space in the shells of gastropods (snails) that arises as a consequence of the shell spiraling inwards. This space is used by some gastropods to store their eggs (a co-opted trait) but is left hollow in others.

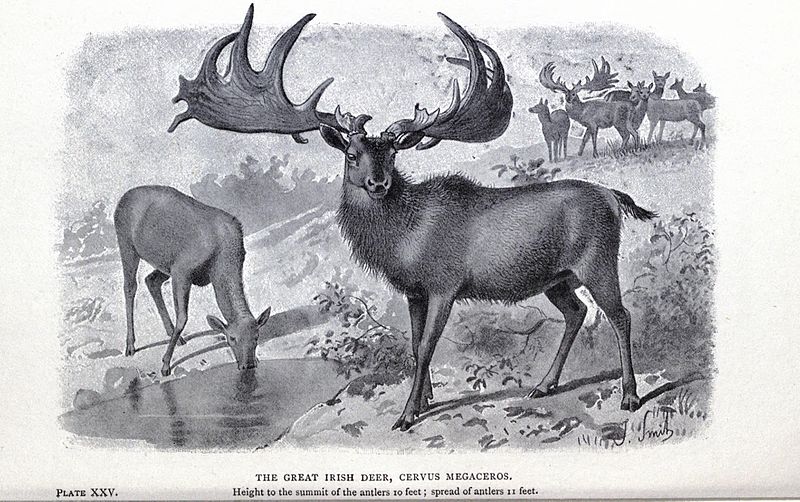

The hump of the great Irish deer is another spandrel. It arose due to the elongation of the vertebrate so that the horned head of the deer could be supported. The hump, through evolutionary time, became patterned and co-opted for sexual selection.

If one assumes that the hump of the deer was an adaptation, it would mean messing up the historical origin of the trait. Doing so might lead to errors in predicting when the trait appeared, or lead to ignoring other important interactions (environment, viral, other animals, etc.).

The examples we have considered thus far have touched upon physical traits, but what about behavioral traits? This is where the debate gets murky. Phenomena like war, language and art were considered by Gould as spandrels of a large human brain. Sure, they help humans get along and become the dominant species on the planet, but they might not have started out with that function as its inherent purpose.

Also Read: What Are Some Of The Most Amazing Signs Of Evolution In The Human Body?

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Evolution The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian .... The University of Washington

- Gould, S. J. (1997, September 30). The exaptive excellence of spandrels as a term and prototype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- (2010) Adaptationism - Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University

- (1998) Adaptations, Exaptations, and Spandrels. The University of California, Los Angeles