Table of Contents (click to expand)

Forensic Chemists utilize art history and state-of-the-art analytical equipment to detect art forgeries that pollute the art world.

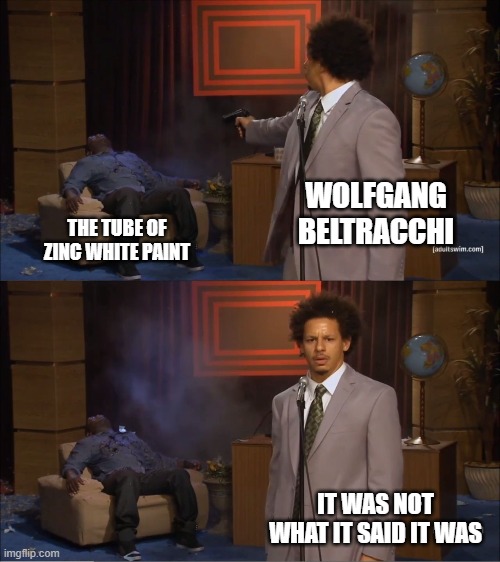

In 2011, a German court held a 40-day trial and convicted the “most spectacular” post-war art forgery circuit in the world. Wolfgang Beltracchi, his wife Helene, and two others were arrested for running a multimillion-dollar art scam creating fake masterpieces. Their scam, which ran for over a decade, suddenly came crashing down, all because of a tiny discrepancy in the white paint that the forger used. He used a tube of zinc white (as opposed to only using zinc oxides) in his painting, which sadly (for him) contained traces of a modern white pigment, titanium dioxide.

In any form of art, the first line of defense against forgeries are the art experts who visually scrutinize to authenticate. However, forgers have come up with increasingly ingenious ideas to trick the experts. Unfortunately for forgers, everything in this world has a chemical story to share. Technology has now made it possible for forensic scientists to look at paintings not just beneath their top layer, but also at a molecular level.

With the help of art experts and historians, forensic chemists use these molecular clues to expose what pieces are the real deal and which ones are fake!

So, how about we delve into a few ways that chemistry helps art detectives solve their great mysteries!

Non-Invasive Techniques

For any kind of procedure, be it medical or forensic, experts look for a non-invasive option. Basically, this means something that wouldn’t require physical entry into the object of interest. Scientists have figured out ways to put not just visible light, but the entire electromagnetic spectrum to use! Different ranges of this spectrum provide us with different perspectives to look at forgeries.

Microscopy

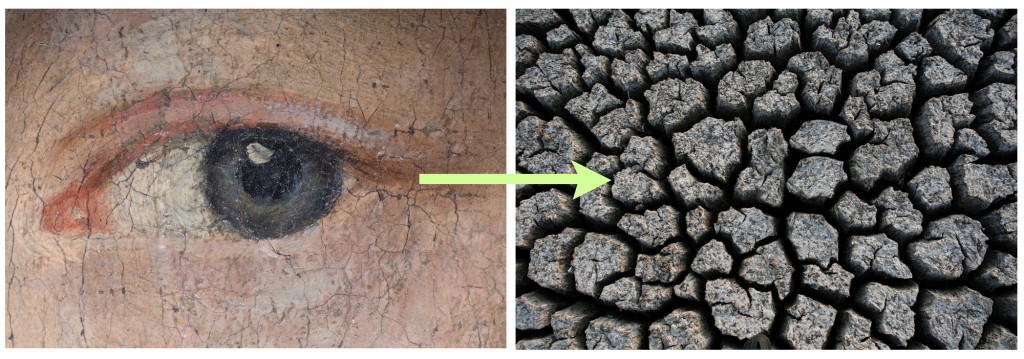

Microscopy uses visible light and powerful lenses to photograph specific regions of a painting. It can magnify the craquelure on paintings to look like mud cracks! Photographs can be taken at magnifications ranging from 100-10,000 X.

Microscopes can help when looking into foreign materials, such as a strand of brush hair, a fiber from a cloth stuck to the paint, or even a partial fingerprint of the painter. A fingerprint obtained from a suspected piece of forgery can be matched with those obtained from an authenticated work of the original artist. Or, if the fiber or brush hair turns out to be synthetic, the investigator can be sure that the painting was made after the 1930s, as the commercialization of synthetic fibers happened after that time.

Ultraviolet (UV) Reflectance Imaging

Painting materials, such as mediums, oils, or varnishes, are made of organic materials. These degrade over time and the slow degradation process gives rise to fluorescence (a green glow) under UV light. So, when UV light is reflected off an old painting, the resulting image shows fluorescent spots due to the presence of organic compounds in the paint.

Even so, forgers found a way around this “tell”, as they can swab varnish from old inexpensive paintings and coat it on their forgeries. To tackle this problem, if a varnish appears too bright in UV reflectance imaging, it is recommended to treat the surface with turpentine oil. This reduces the brightness of the glow and helps investigators analyze the fluorescence from the actual paint layer. If the painting appears dark, it means the painting is relatively new or made of synthetic materials, which is highly improbable for any paintings made before the middle of the 20th century.

X-Ray

X-ray imaging or radiography reveals details about paintings that only Superman could see. When beams of X-rays are targeted, they pass through the layers of paints and create a contrast image. The regions where restorations were done, or where the paint layer is thick due to overpainting or possessing heavy metal objects like nails and screws (definitely a modern invention), the images appear brighter in the X-ray image.

These X-rays sometimes reveal hidden images, signatures, or a completely different painting below the actual artwork. (Forgers often paint over old paintings to make their work appear old and authentic). Tom Keating (a British forger) has claimed to have written swear words with white lead on his forgeries for a radiographer to find them.

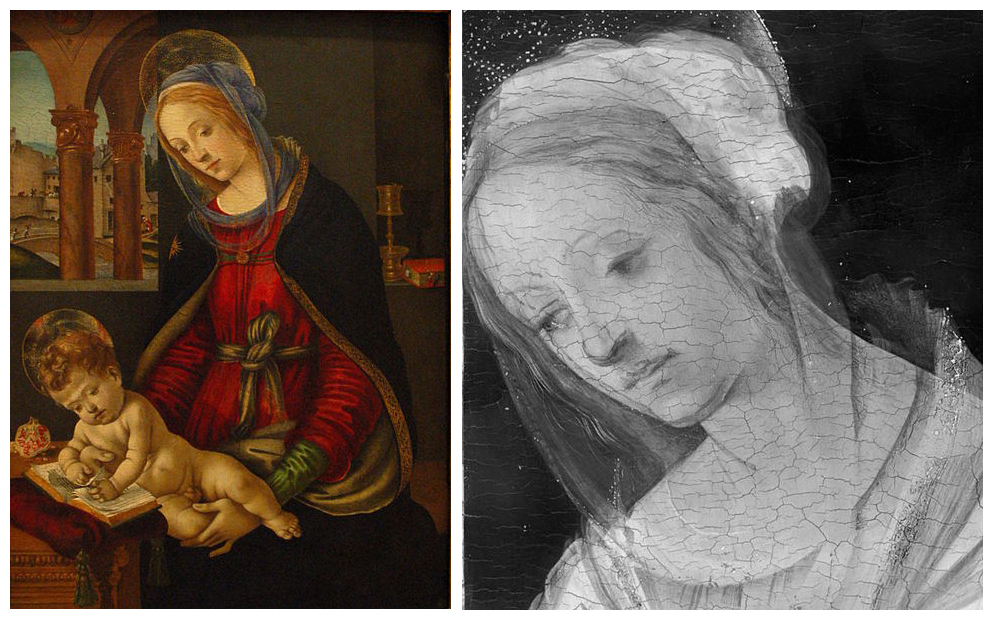

Infrared Scanning/ Reflectography

Infrared light not only helps you turn on your TV from the couch, but it also helps forensics experts take a look beyond the paint itself. When a painting is exposed to IR light, it penetrates through layers of paint, as they are transparent to IR. The wooden support or the primed canvas absorbs the infrared light to enhance many details that may look insignificant under normal light.

Infrared Reflectography can reveal underdrawings or sketches hidden behind the artwork. Materials such as charcoal are transparent to X-rays, but absorb IR light and show up in the image.

Most painters have a signature style of making an underdrawing before they start painting. Thus, an IR scan can easily help spot a fake if the style of underdrawings does not match those of known original works.

Also Read: How Exactly Is A Piece Of Art Faked?

Invasive Techniques

Over the years, forgers have become exceptionally good at faking art, but the art of detection has kept up. Forensic scientists use microscopes to remove a tiny amount of sample (too small to be seen by the naked eye) from the painting. Analytical equipment has become very powerful and sensitive over the years. They can dredge out the entire molecular history of a painting from a sample as thin as a human hair.

While reading this article, you may have thought, we’re talking about old objects, so why isn’t there any mention of carbon dating? Good thinking!

Radioactive Carbon Dating

Anything alive or that was once alive has a little bit of radioactive 14 C in them. Organisms replenish their 14 C concentration via atmospheric carbon dioxide or food. Cosmic rays convert the Nitrogen present in the atmosphere to 14 C, which later forms non-toxic CO2 in the air. However, once an organism is dead, the amount of 14 C in their body cannot renew, so that amount starts decaying. Thus, carbon dating any natural organic material tells us how long ago that particular thing was alive.

Carbon dating a canvas cloth, paper, or stretcher (all plant materials) of a painting would give experts some idea of how long ago it was made. However, this approach faces two major hiccups: 1) There is no guarantee that the material was used soon after the manufacturing; and 2) Forgers found a way to beat this test by using era-appropriate materials from cheap, older paintings.

If forgers are clever, scientists are cleverer. They ditch plant materials and date the paint components instead. Components such as linseed oils, egg tempera binders, and rabbit skin glue are made from short-lived animals. Dating these can give them a fair idea as to when it was painted.

The nuclear bombings and testings during WWII and the Cold war considerably increased the amount of 14 C in the air. If a painting was made pre-WWII, the 14 C would be low, because it was encased in a varnish, but anything made after 1945 would likely be beaming with atomic age residue.

The suspicion of forgery arises even when the concentration of 14 C is really low. Sometimes the results date back to 20,000 years ago (yes, the Stone Age). That would mean the binders are synthetic, as synthetic varnish and binders are derived from petroleum products. Their source of carbon is geological, and geological carbon sources are devoid of the radioisotope 14 C.

Non-linear Microscopy And micro-Raman Spectroscopy

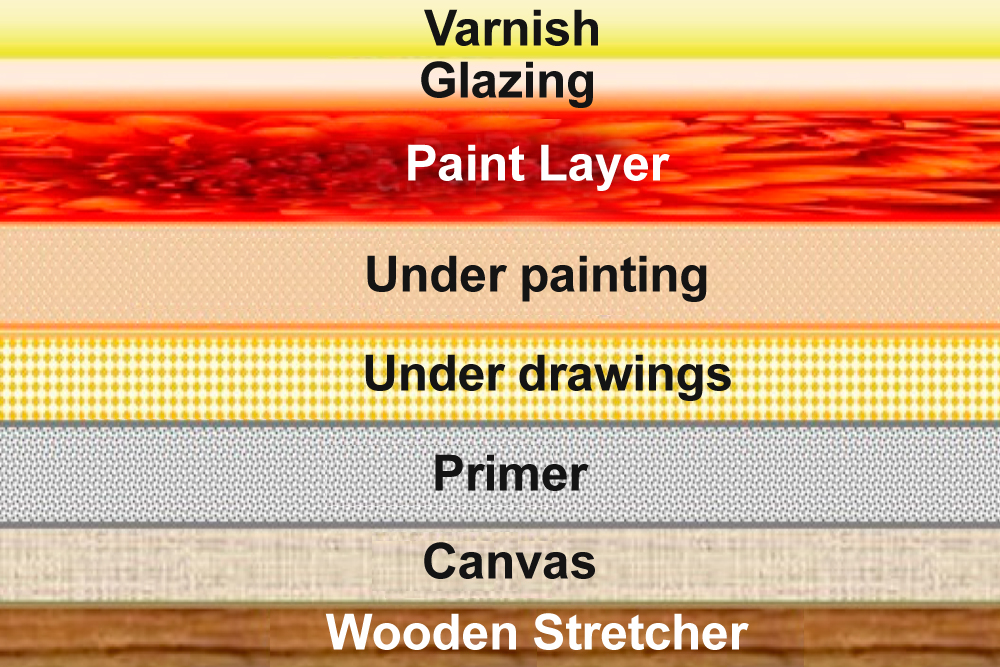

These might sound like big scary words, but their function is quite basic. A non-linear microscope takes images of a sample in the vertical direction, like the side view of a layered cake. This reveals information about the different layers in a painting.

Now, each of these layers can be subjected to micro-Raman Spectroscopy. Most non-synthetic pigments are obtained from minerals, and minerals usually have a crystalline structure. Crystalline solids interact with light and uniquely scatter them, and every mineral has a unique scattering pattern, like a fingerprint. The scattering patterns help forensic chemists determine which chemical compound is present in the pigment.

For example, if a painting is from the early 19th century, the blue pigment should give a scattering pattern identical to the mineral lapis lazuli. Instead, if it matches with that of synthetic ultramarine blue, or the red pigment shows the presence of cadmium red (another 20th century invention), then there is definitely a problem!

Also Read: How Does Science Help Solve Crimes? The Real Life Science Of Crime Scene Investigation And Forensics

Conclusion

Even though the tale of art forgers is as ancient as art itself, modern scientific techniques have created havoc in the lives of modern forgers. Such experts are pushing forward to eradicate forgery from the art world entirely. This is critical because the worth of a piece of art isn’t just about how it looks… its historical and monetary value lies in the authenticity of the ideas and the style of expression.

Finally, this is an inclusive but not exhaustive list of tools that art forgery experts utilize to find the truth. There are many other techniques with complex names that we didn’t discuss, but these are the major modes of detection employed around the world to ensure authenticity!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Craddock P. T. (2009). Scientific Investigation of Copies, Fakes and Forgeries. Routledge

- RMS | Forensics and Microscopy in Authenticating Works of Art - www.rms.org.uk

- (PDF) "A study of uv fluorescence emission of painting materials". ResearchGate

- Taft, W. S., Jr., & Mayer, J. W. (2000). Detection of Fakes. The Science of Paintings. Springer New York.

- Chemistry Solves the Mystery. The American Chemical Society

- Hodgins, G. W. L. (2019, June 18). Identifying art forgeries by radiocarbon dating microgram quantities of artists’ paints. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Beck, L., Messager, C., Caffy, I., Delqué-Količ, E., Perron, M., Dumoulin, J.-P., … Serneels, V. (2020, June 12). Unexpected presence of 14C in inorganic pigment for an absolute dating of paintings. Scientific Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- (2005, August 2). (Sackler NAS Colloquium) Scientific Examination of Art. []. National Academies Press.