A single global currency is not possible in its current form as, among other reasons, it would require all nations to agree upon a single monetary authority.

If you’ve ever watched any Star Wars films, you’d know that there’s a well-defined unit of currency that prevails across the galaxy. They call it the Galactic Credit Standard or the Imperial Credit, depending on which era of films you’ve watched. This begs the question for some die-hard fans—how did a whole galaxy far far away agree upon a universal currency?

Despite being in a constant state of turmoil, the vying factions managed to have some semblance of standardization in their unit of value. We can’t even do that on single planet, let alone across hundreds of star systems!

In fact, according to xe.com’s ISO 4217 list of currency codes, there are presently a whopping 162 currencies in circulation around the world. Wouldn’t it be simpler to have a single global currency?

The idea may sound quite outlandish and rather fanciful, but I’m certainly not the first one to consider it. Eminent scholars with strong credentials and more letters behind their name than their actual names contain have proposed the idea throughout the better part of the 20th and 21st century.

In 1961, Nobel Laureate Robert Mundell proposed a theory of “Optimum Currency Areas”, which involved areas where the national currencies would be closely related to one another. He provided the example of Europe, which back then did not utilize the Euro.

These optimum currency areas seemed like a precursor to a single currency system currently prevalent throughout the region.

In 1984, Richard Cooper, a Maurits C. Boas professor of International Economics at Harvard University, went ahead and actually proposed the radical idea of “the creation of a common currency for all of the industrial democracies, with a common monetary policy and a joint Bank of Issue to determine that monetary policy.”

In fact, he predicted a universal currency to exist by 2010! In 1988, even ‘The Economist’ famously predicted the formation of a global currency called ‘Phoenix’ by 2018.

2010 has come and gone, and so has 2018, but we still aren’t remotely close to achieving a global currency.

There are two sides to this coin (see what I did there?) and we will discuss both of them.

But first, a bit of context.

The Origin Of Currency

Human civilization began transacting with each other when one person wanted something that the other had. It could have been an apple, a tree branch or whatever else was “trending” back then.

However, the transaction was only possible if the other also wanted something that the first person had. If I have an apple, but I want a mango, I would need to find somebody with a mango who may like my apple instead.

As you can imagine, this wasn’t easy. We needed a more uniform store of value that was also more convenient to carry. Imagine lugging around a cart full of sheep and calling it your ‘wallet’.

The first form of money was introduced at some time during the 7th century BC, an act of governments using pieces of metal to pay their debts to mercenaries for their services. These “coins” were essentially symbolic. They were a token symbolizing that the government owed them something.

The government happily accepted these back in return to cover the citizens’ tax obligations.

Therefore, these symbolic pieces were in great demand amongst the citizens, who began accepting these as payment for all goods and services. The symbols of debt became stores of value that could ultimately be used by citizens to pay their taxes. It was certainly easier than paying two sheep, three figs and five apples as tax.

What this means is that the whole idea of currency was not a product of meticulous planning and execution, but instead came about serendipitously.

Of course, this leads to a pertinent question—is it the most efficient strategy today?

Also Read: Who Makes Bills And Coins For An Economy, And How Do They Decide The Value Of Each?

Why Should We Have A Single Global Currency?

If the very same government from the 7th century BC ruled over the entire world today, we might happily be trading those symbols of government debt with each other without any qualms.

However, since then, countless new nations have been formed, a vast array of unique monetary systems have been introduced, and an even greater variety of currencies has been printed.

That approach would still be fine, if each nation operated as a self-sustaining economy with no cross-border transactions. However, this is clearly not the case.

The rapid growth of communication technology and drastic improvements in transport links have created a global economy where international transactions in multiple currencies are commonplace. Multiple currencies give rise to added steps in the otherwise simple exchange of goods or services for payment, and also lead to greater transaction costs.

For example, a laptop manufacturer in the United States can purchase their hard drives from Japan using Yen, procure their screens from South Korea by paying in Won and assemble the device in a Chinese factory whose contract is valued in Renminbi (note: this is a gross oversimplification of the laptop manufacturing process).

The US manufacturer wants to pay the hard drive supplier in US dollars, but can’t, so they must find someone who has Japanese Yen and is willing to trade them for US dollars.

Once he finds such an institution (typically a bank), they make the exchange, for which the bank charges a fee, and then proceeds with paying the Japanese supplier for their goods.

Now, the US manufacturer has both Yen and US Dollars. However, the Korean supplier expects payment in Won. It’s up to the US manufacturer to exchange their US Dollars for Won. They go back to the bank for yet another conversion, which adds yet another fee. After that, when contract payment for the Chinese factory comes due, that’s another boost in transaction fees for the bank.

Furthermore, the added ordeal of converting one currency into another before each relevant transaction adds a multitude of costs. According to Bloomberg, the average daily trading in the Forex markets is about $6.6 trillion. Morrison Bonpasse, the President of the Single Currencies Association, states that about 0.048% of daily average trading volumes is paid towards transaction costs. These are costs that go towards paying the currency traders, their support staff, computer systems, etc. This amounts to approximately $3 billion per day. Assuming 260 trading days in a calendar year, the annual cost of foreign exchange transactions is about $780 billion. Unequivocally, that’s a lot of money! If we had a single universal currency, the world would save just under $800 billion dollars each year in transaction costs alone.

When dealing with multiple currencies, companies also need to mitigate the risks associated with fluctuations in currency exchange rates. The aircraft manufacturer Airbus estimated that for every cent that the Euro gains against the US Dollar, the company’s profit declines by 100 million. In order to mitigate such unprecedented falls in profitability, companies “hedge” themselves against such risk. It’s a complex financial strategy done through some equally complex financial instruments. Essentially, it’s a lot of effort and costs a lot of money.

One could argue that the rise of multiple currencies for conducting transactions has just created another form of the barter system, with intermediaries adding on to the cost of doing business. A single universal currency regulated by a global monetary union would nullify the majority of the transaction costs and eliminate all forms of currency exchange risks.

However, let’s also try to understand the other side of this coin.

Also Read: Why Doesn’t The Entire World Have Just One Currency?

Why Shouldn’t We Have A Single Global Currency?

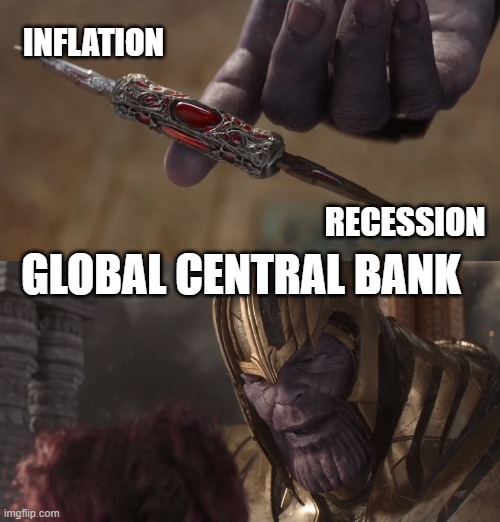

A single global currency would be governed by a global central bank. This bank would essentially be responsible for the monetary policy of the whole world. However, each nation has its own set of issues. A nation’s monetary policy can be a powerful tool to mitigate issues like inflation or recession. For example, during a recession, citizens curtail their spending, which leads to businesses not earning enough, in turn forcing businesses to halt investment in new capacity and even laying off some of their workforce. Laid-off workers would have a strong desire to save, rather than spend what money they have, leading to a further decline in consumer spending in the economy. In such a scenario, a country’s central bank can intervene with adjustments to its monetary policy, such as bringing down interest rates, printing fresh currency, buying government bonds etc. to increase the money supply and jumpstart the economy. On the other hand, if a nation were facing severe inflation, the central bank would step in and raise interest rates, ask banks to maintain greater reserves and essentially reduce the money supply in the economy.

If a global central bank were to set a global monetary policy, ideally, it would need to balance conflicting and perpetually shifting priorities of all nations; some could be suffering a recession while others might be battling hyperinflation. Designing a policy sophisticated enough to cater to the needs of all the world’s nations would be an impossible feat.

Kenneth Rogoff, a Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics at Harvard University, also identified a slew of other issues that would arise if we were to have a global central bank. A global central bank would be difficult to monitor or hold accountable without a global government in place. As a result, it may operate without any oversight whatsoever, which could be problematic. Moreover, the appointment of a global central banker may become rapt in political conflict. Who would decide who gets to govern the global central bank? It would be difficult to have an entirely unbiased selection process. Furthermore, a centralized authority with no oversight may also lead to some anti-competitive concerns. We are in an era of disruptive financial innovation, one that is paving the way for a much more evolved financial future. A central authority that may view certain innovations as a threat could choose to constrain these changes by leveraging the monopoly position that it would enjoy over the global economy.

Possibilities For The Future

While there are compelling arguments both for and against a single global currency, there may be a middle ground of possibilities. Robert Mundell’s idea of having ‘Optimum Currency Areas’ may still be viable. Just like the European Union, we could have collectives of countries in a similar state of development and geographical proximity, pursuing common currency objectives. Alternatively, instead of a single currency, we could have a handful of currencies. The IMF’s global reserve asset, the ‘Special Drawing Right’ (SDR) is exactly that. Currently, the SDR consists of the US Dollar, Euro, Chinese Renminbi, Japanese Yen and Pound Sterling. These are currencies supported by arguably the world’s most resolute economies. The SDR or something similar could be used more frequently as a store of value in cross-border transactions in order to avoid many of the associated conversion costs. Yet another possibility is the ‘dollarization’ or ‘euroization’ of the world, wherein nations opt to accept the US Dollar or the Euro as their national currency, thus turning an already established currency into a universal currency.

Finally, we must also remain open to the possibility that the best system of currency for the global economy may be a completely novel stroke of genius that has yet to be proposed!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas Robert A. Mundell The .... Simon Fraser University

- Morrison Bonpasse, (2008) The Single Global Currency - Common Cents for Commerce - ResearchGate - ResearchGate

- K ROGOFF. Why Not a Global Currency? | Rogoff | Scholars at Harvard. Harvard University

- A Monetary System for the Future | Foreign Affairs. Foreign Affairs

- (2004) A Global Currency for a Global Economy - JSTOR. JSTOR

- Global Currency Trading Surges to $6.6 Trillion-A-Day Market. Bloomberg Television

- ISO 4217 Currency Codes - Xe. Xe.com

- COVER: "GET READY FOR A WORLD CURRENCY". altcoopsys.org

- Is it time for a 'true global currency'? | World Economic Forum. The World Economic Forum

- Monetary Policy: Stabilizing Prices and Output. International Monetary Fund

- (2006) Development of a Worldwide Currency: Is it Feasible?. The Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University