Table of Contents (click to expand)

Despite having the best methods for producing a given commodity, it is still wise for a country to indulge and gain from specializations in trade due to reduced opportunity costs.

Any exporter who chooses to sell their goods across borders must pay close attention to pricing, costs and quality in rival countries. Figuring this out can be overwhelming, as multiple factors come into play.

Domestic and foreign governments alike offer select subsidies, impose tariffs and non-tariff barriers, and enter into bilateral and multilateral trade agreements, as well as various other arrangements, when it comes to trade. These also differ from sector to sector and product to product.

All of this adds additional layers to the pricing of a product. It can be challenging for an exporter to find the answer to such a complex question.

Theory Of Absolute Advantage

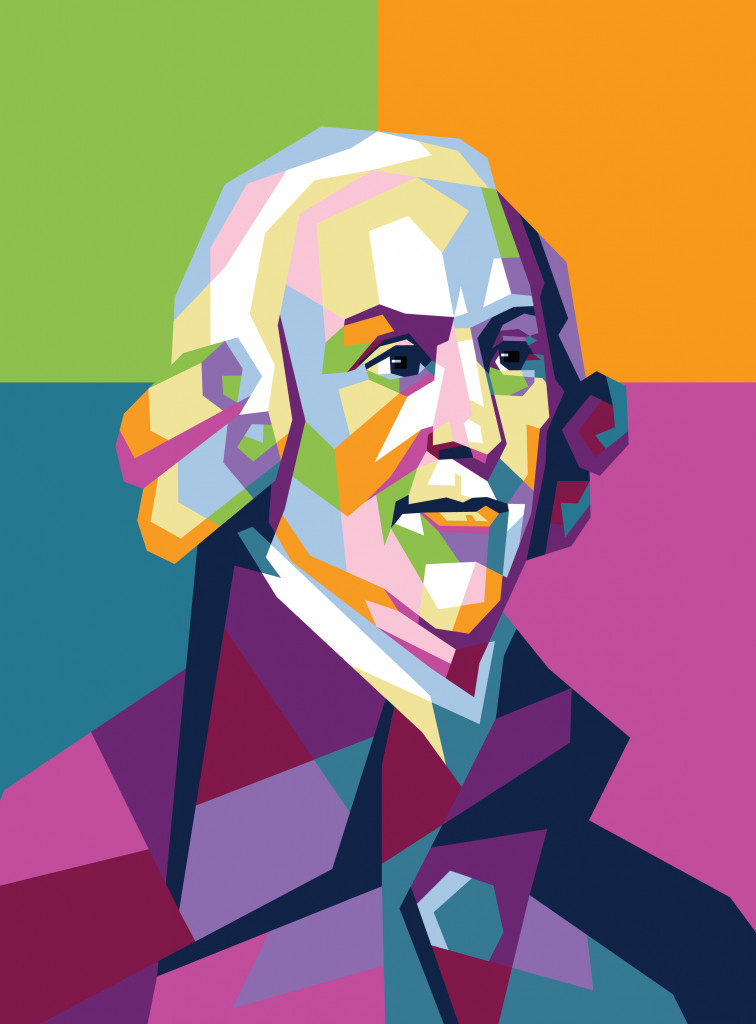

In the ‘Wealth of Nations’, published in 1776, Adam Smith proposed the idea of absolute advantage as a recipe that countries can adopt while choosing to specialize before indulging in trade.

Before two countries enter into trade, they must check if the same amount of resources or inputs produces an acceptable amount of the desired output. Simply put, the focus is on efficiency. The more efficient a country is, the fewer inputs it will need to produce one output unit.

Hence, they can choose to specialize in producing that particular commodity for trade.

Therefore, before two countries enter into a trade contract with one another, assuming no other cause for fluctuation as a result of exchange rate changes, trade barriers, domestic movement of labour, or quality differences, it was believed that the country with the lower input cost should specialize in that commodity. This would further lead to specialization, reduce costs and increase gains from trade.

For Smith, the primary input was labor; hence, he measured the quantity of labor required to produce one commodity of good across two nations. The country using less labor should specialize in the respective commodity, generate funds, and then use that to purchase commodities and services from other nations.

When countries focus on specialization, they can focus solely on producing that good or service at a top level; the increased fund inflow due to specialization will benefit both entities participating in an exchange.

This is, however, not necessarily, the only way to look at trade. Countries can also choose to specialize in producing a good at a lower opportunity cost. It does not necessarily imply that the specific country deciding to produce that good must ensure that it is of superior quality or in a high volume.

Also Read: Is The Curse Of Montezuma Still Relevant For Modern-Day Economies?

Theory Of Comparative Advantage

Comparative advantage is a new perspective on trade brought forth by Ricardo in his book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation in 1817.

Let’s use a single example to understand both concepts. The US is gifted with abundant natural resources, a skilled labor force and a strong currency. Even so, it can benefit from trade, despite being able to produce all its needed goods efficiently if it decides to do so, as natural and man-made resources are on its side.

Smith would advocate that since resources used to produce any good by the USA are minimal, it should go on producing them. However, Ricardo would disagree. Even if they’re able to produce any good with the least amount of resources, the USA should calculate its comparative costs. This considers opportunity cost, which is the cost of any choice because the next best alternative is missed.

For instance, if the US chooses to produce mangoes instead of apples, the opportunity cost of producing mangoes is apples. The US has lost the opportunity to produce apples by choosing to produce mangoes. It is imperative to give that “cost” (or potentially lost profit) a number. In this case, by choosing to produce mangoes, how many kilos of apples were not produced? Was this the right choice in terms of the revenue lost?

Keeping this choice in mind, even if the US can produce superior apples, it may still go on to produce only mangoes and exchange them for apples, provided that by exchanging one mango, they get two apples from another country. Had they chosen to produce this domestically, for one mango, they might have had to forego one apple (assuming land, fertilizer, and labor requirement is the same for mangoes and apples). Thus, they are gaining two apples by choosing to trade in mangoes.

Hence, a country can have an absolute advantage in producing both commodities, but still benefit from trade if they consider their opportunity costs. Weighing decisions through opportunity costs helps a country decide how to invest resources to maximize returns, rather than produce everything domestically.

Two centuries later, these concepts still find relevance. Although there were several assumptions made by both economic thinkers, such as the effect of ongoing policies not being taken into account, or the costs associated due to tariff and non-tariff barriers. Even exchange rate fluctuations have been assumed away in these models.

Think about it, even in terms of absolute advantage, developing countries may produce the same output with far more inputs, yet it is cost-effective to make these countries into sweatshops! This is because even though the quantity of inputs are high, labor costs are low, and the absence of strict law enforcement makes the endeavor cost- effective.

Also Read: Are Prices Only Determined By The Quantity Demanded?

How Are These Theories Applied Today?

While it is widely admitted that measuring comparative advantage is very difficult, due to the nuances of policies implemented across countries and their fluctuating nature, one commonly used indicator is the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA). With this indicator, the export quantity of one country for a commodity is compared with the total exports in the world or region.

For instance, if a country’s RCA in rice is high, it would mean the advantage to producing rice is greater than what the exports are in the region for that commodity or in the world. The country itself can choose this benchmark. If the country’s RCA is high, meaning greater than 1, its rice exports are greater than all other countries’ exports for that commodity in that region.

This suggests that the country is a more efficient rice producer than any average country in that region or across the world. This interpretation would change based on the benchmark chosen.

Again, it is observed that despite a country having a higher RCA for a given commodity, it still might choose to produce something else. This discrepancy is where the speculation comes in—the role played by policies of tariff and non-tariff barriers that affect a country’s overall export basket.

How well do you understand the article above!