Table of Contents (click to expand)

Economics is a discipline that draws its findings from a wide range of subjects. Be it sociology or mathematics, an economist must find a way to reason with many variables to draw their conclusions!

The National Academy of Sciences defines science as ‘the use of evidence to construct testable explanations and predictions of natural phenomenon, as well as the knowledge generated through this process.’ Being able to use evidence to arrive at explanations that can help one precisely predict what happens next is what sciences aim to capture.

Repeated experimentation under the same conditions should reveal the same result, come what may. This holds true when the subject being studied is not human. Thus, the results of a scientific experiment conducted anywhere can be applied in any other corner of the world. This results from its ability to generate universal and valid results.

What Is Economics?

The word economics is derived from the Greek word ‘oikonomia’, which means ‘management of household affairs’. Management involves choosing between multiple options available at your disposal. In economics, this means choosing between alternatives for a desired end.

When it is macroeconomics, the desired end is a nation’s well-being; when it is microeconomics, the subject of study is often that of an individual. Both varieties can be steered by policy design. On the micro level, one may not necessarily draft a policy document per se. Still, one does spend time thinking or planning how they might choose to spend their income for consumption, investments etc. When performed at the level of an entire economy, this act is systematized as separate policy documents.

Also Read: How Does Your Social Class Influence Your Understanding Of Economics?

What Makes Economics A Science?

Economics is also called economic sciences by the Nobel Prize committee. Economists heavily rely on data as a guide to policy making. The term “sciences” was added in the late 19th century to distinguish fields from their contemporary counterparts that often used quackery or unreliable tools of assessment.

For instance, astronomical sciences became a separate field from astrology. This was done to differentiate astronomy from astrology, which used ancient myths to study constellations. Astronomers wanted to present themselves as scientists with verifiable results, not just theories intended to sway popular discourses.

The second Nobel Prize in Economics was given to Paul Samuelson for being able to scientifically analyze economic theory. This gave birth to the idea of a modern economic theory, as it was now testable.

The rigor of using mathematics to arrive at an essential understanding of the economy cannot be denied.

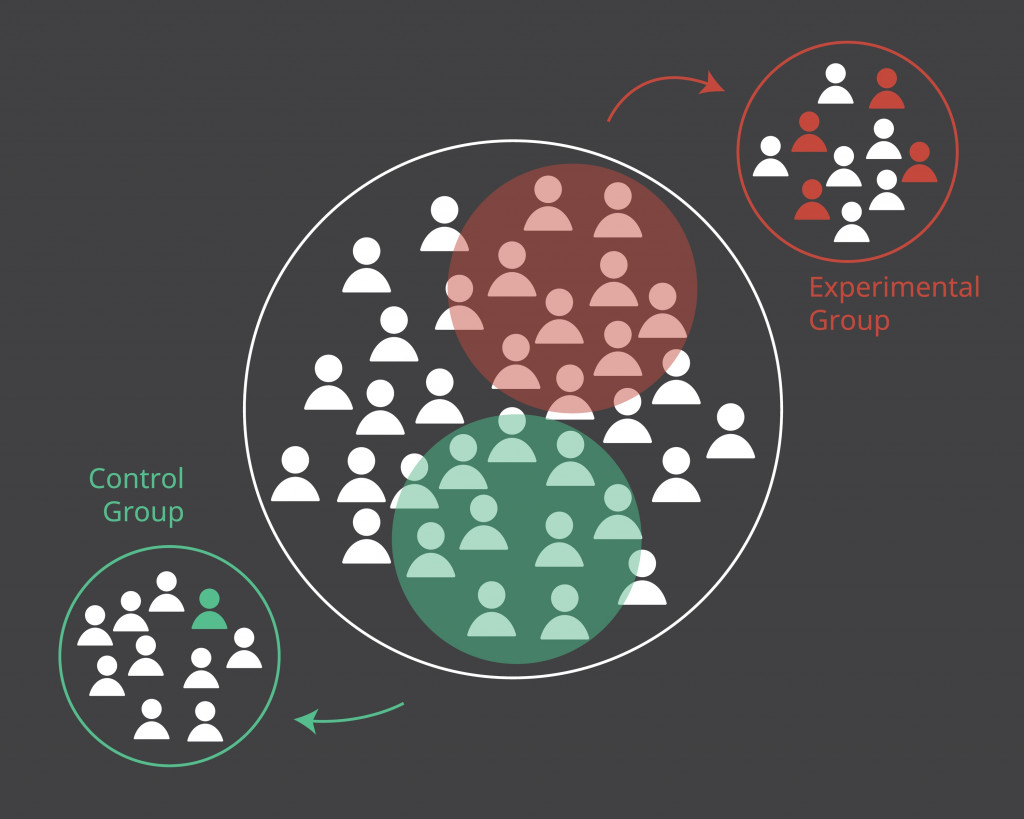

The use of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT), for which Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo won the Nobel Prize in 2019, is another more recent example. RCT attempts to use a control group vs. a population group before administering any treatment.

The treatment in economics takes the form of inputs, including books, teachers, imported products, government policies etc. The test checks whether administering any input positively impacts the control group. If so, it is chosen as a policy intervention tool for the population.

Aside from RCTs, economics also draws many of its concepts from Physics and Mathematics, as there is a need to optimize choices by applying limits and differentiation to arrive at equilibriums.

However, unlike other fields of science, economics can never claim a perpetually repeatable level of precision for its results. Contextualizing always takes precedence before any economic theory can be applied.

Also Read: How Do Economists Predict An Upcoming Recession?

What Makes Economics A Social Science?

Economics relies heavily on mathematics and physics to explain consumer and producer choices, such as buying a house, deciding wages and profit rates, etc.

Even erstwhile economists like Keynes and Smith have expressed concern over overt mathematics becoming the dominant approach. This dominance became prevalent in the post-World War 2 era. Before this, economics was just another subject like sociology or philosophy. It was accepted that humans are not algorithms, as they uniquely respond to a wide range of incentives and norms that go against what standard neoclassical equilibrium models present.

The famous Lucas critique states that economic agents anticipate changes in policy intervention and shape their behavior accordingly. It is only in social sciences, where humans are the subject, that such a possibility exists. Unlike in a laboratory, where a scientist can control their environment during an experiment, humans are a very unpredictable and highly adaptable species.

Economics studies how humans relate to their resources. This relation heavily varies from one economy to another. Of course, inflation means the same everywhere on the globe, but the level of inflation that a developed country (i.e., the US) can withstand, as compared to a developing country (i.e., India), will vary widely. These causes can originate from multiple factors, such as political, social, and climatic factors.

This is also why economists rarely have a solid consensus on any policy intervention. Multiple motives and ideologies come into play when deciding any policy intervention. Every ideology has its own theoretical underpinnings that dictate and shape that policy intervention’s content.

Therefore, it becomes even more important for economists to realize when a situation demands the intervention of an anthropologist, sociologist or even a climate expert. An economist can never work in an isolated silo. These interactions fuse the social aspects of economics as a social science subject.

What an economist can bring to the table is limited in terms of how an individual or an economy can produce a certain level of output. However, questions regarding how this output is produced and for whom it is produced involve a deeper dive into the prevalent societal structures.

Conclusion

All a priori logic in science is confined to logic and mathematics, whereas for economies, the field is wide open.

The question of what is right or wrong for an economy will always have an unequivocal answer. This judgment is outside the scope of science. A society, based on its inherent structures, will collectively arrive at this decision. This decision would result from both quantitative factors and other factors, such as cultural norms, beliefs and judgments.

It is overwhelming for an economist to consider multiple perspectives and try not to obfuscate them under assumptions. Again, while certain assumptions will seem relevant for some economies, when scaling that to other economies, an economist must be mindful of making assumptions, as the context will inevitably be different.

Some economists, like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Piero Sraffa and Krishna Bhardwaj, have been able to do just that while studying capitalist economies. They’ve been able to build theoretical structures that allow economists to gauge the impact of societal structures on key issues of production, distribution and exchange.

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Leshem, D. (2016, February 1). Retrospectives: What Did the Ancient Greeks Mean by Oikonomia?. Journal of Economic Perspectives. American Economic Association.

- Focardi, S. M. (2015, July 21). Is economics an empirical science? If not, can it become one?. Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics. Frontiers Media SA.

- Is Economics a Science? by Robert J. Shiller - Project Syndicate. Project Syndicate

- Economics: an art not a science - News & insight. Cambridge Judge Business School