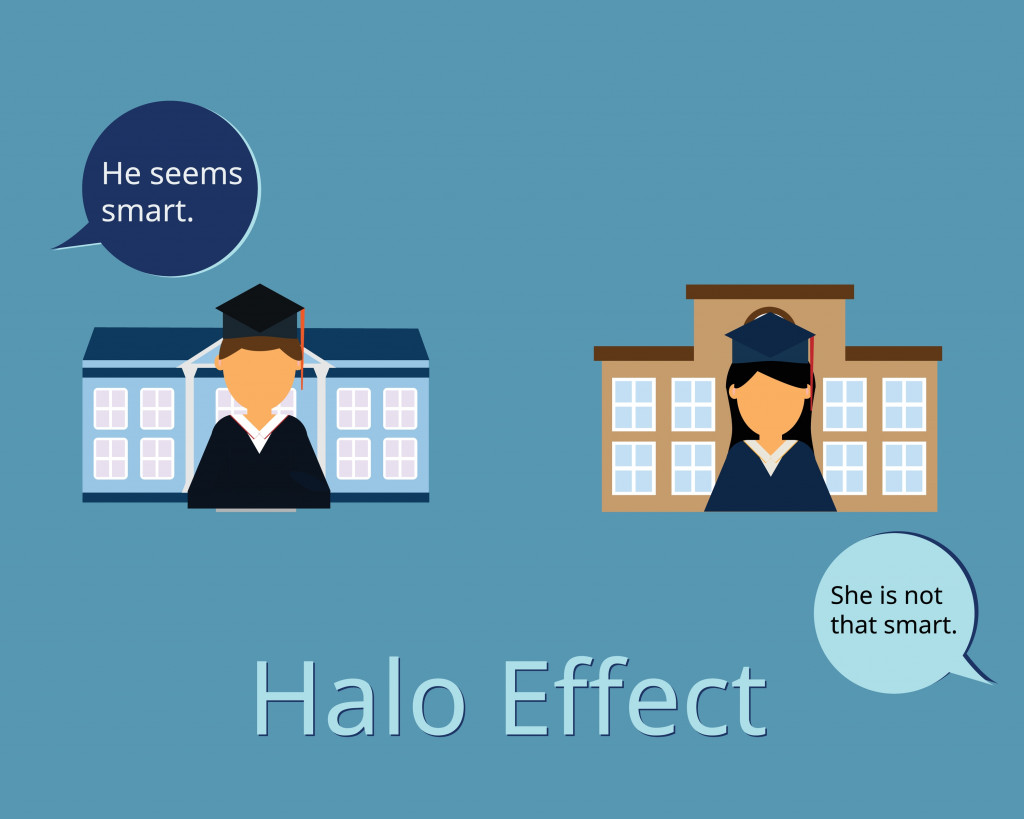

The halo and horn effect influences our judgement. We recognize one good or bad trait in a person, and thus we assume them to be good or bad as a whole,

Do you think you judge people with logic and without bias? Have you noticed yet how the halo and horn effect impacts your interactions?

We all know that first impressions are very important. It is often the first impression of a person that ends up deciding the entire course and nature of our relationship with them. This ranges from getting into a high school clique to acing (or botching) an interview.

However, is relying on first impressions too misleading? Are we assigning people halos and horns based on some noticeable quality, and then stubbornly and illogically basing our entire character judgment on that?

Our Unconscious Judgments

The halo and horn effects are types of cognitive biases. A cognitive bias is an error in thinking that happens because we subconsciously misinterpret information.

The world around us is complex. It would take a lot of time for us to gather and process all the information necessary to arrive at decisions that are only backed by logic and rationality. The time and the information needed for this simply may not be available, so we fall back on assumptions—unconscious biases that we have in place—to make quick decisions.

The Halo And Horn Effect

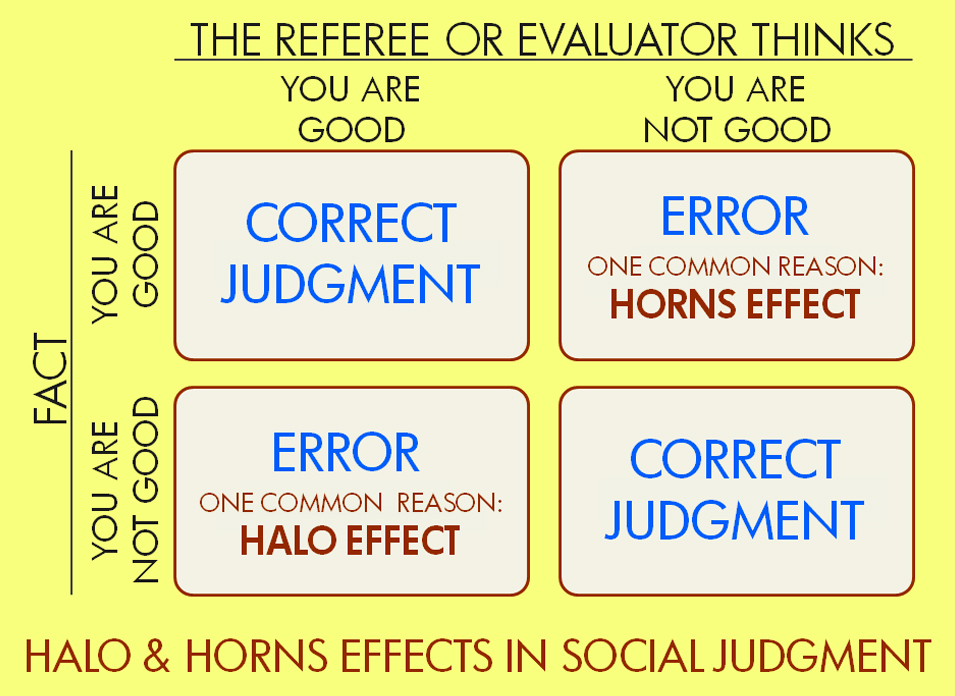

The halo and horn phenomenon refers to us making judgmental errors based on a single noticeable characteristic in a person. It was first noted and documented in a 1920 study by Edward Thorndike.

Thorndike’s study involved corporate employees. It found high and even correlations between estimates of traits like intelligence, skill, reliability, physical traits, character, and so on. These judgments were considered to be colored by a generalization of people as either good or bad.

To put it simply, we notice one good thing about an individual, and then we assume them to be “good” regarding other things too. On the other hand, if we notice one bad thing about them, we assume them to be bad when it comes to other things. We take one trait and make it the ‘halo’ or the ‘horn,’ and root all further judgments on that.

These good and bad traits that we notice don’t have to be objectively good or bad things; they only have to seem that way to your subconscious brain. This may be fueled by damaging stereotypes that even we ourselves do not condone. It also may be based on some superstition that we know is irrational.

When we don’t have sufficient information about something, our brain attempts to fill in the details by connecting it with what we do know. The tricky part is that it’s very hard to tell the difference between what we know to be true and what we assume to be true. It’s very hard to even recognize that we’ve made any assumptions at all.

Also Read: What Is The Fundamental Attribution Error?

The Halo Effect

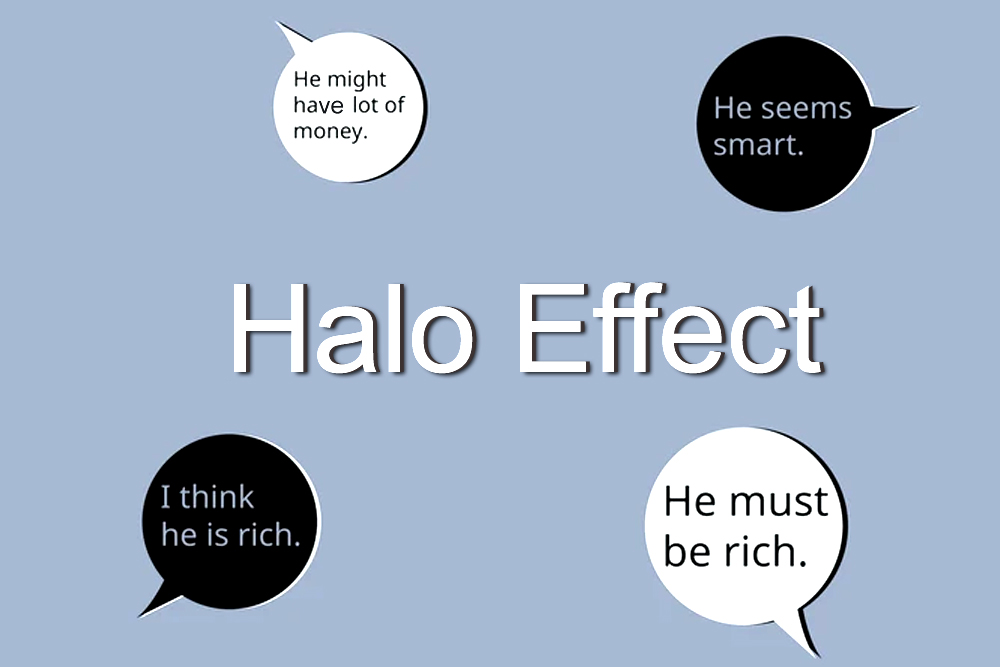

Imagine that we’re meeting a person for the first time. They are well dressed and well-groomed. We see and recognize that positive trait, but then, based on this, we somehow make an assumption that the person also possesses other positive characteristics. For instance, we might subconsciously assumed that they are wealthy and competent.

We note one characteristic of a person that we consider positive, and because of that, we associate other positive traits with that person.

Not only do we think more positively of them, but we also tend to overlook their negative traits. If we first perceive them as competent, then a small misstep on their part would be forgiven more easily, even though, keep in mind, they might have done nothing to earn that tag of competence in the first place.

This is the halo effect. The halo effect, particularly in relation to attractiveness, boils down to “what is beautiful is good.” Studies have shown that physically attractive people are assumed to have a better personality, be more competent and be more successful.

Also Read: Why Do Braggarts Tend To Be Incompetent?

The Reverse Halo Effect

The reverse halo effect is when a perceived positive trait leads to a negative evaluation of a person.

Stereotypes like “rich people are rude and shallow” or “attractive people are vain and egotistic,” are some presumptions that drive the reverse halo.

“The dumb blonde” or the “beauty or brains” tropes are often associated with the reverse halo effect. When you meet someone that looks attractive, there is a likelihood of you judging them as less intelligent. The same goes for being good at activities like sports, i.e., “the dumb jock” stereotype.

The Horn Effect

Imagine that your co-worker comes to the office in a t-shirt and faded jeans with unkempt hair every day. Even if you know absolutely nothing about them, their attire and grooming suggest to you that they are incompetent or slovenly. You now assume that they are lazy and probably just lounge about at their desk doing absolutely nothing all day, despite having seen nothing whatsoever to support this.

You recognize one trait in a person that you consider negative, and it causes you to associate other negative traits with them. We make a negative character assessment, and also tend to overlook or underplay their positive traits.

Studies have also shown that a negative impression is much stronger than a positive one. That is, it doesn’t take much to muddy the waters when you judge someone.

It is also worth repeating that the negative traits we so often consider as a ‘horn’ in the people we encounter in our day-to-day lives are rarely objectively negative traits.

This is the horn effect, also known as the negative halo effect.

The Halo And Horn Effect In The World Around Us

If we think about it for a moment, we would recognize that these are not just obscure psychological phenomena. Most of us have been doing this all our life. We like to think that our judgments are always rational, logical, grounded in facts, and not perceptions, but that is rarely the truth. We are ruled by our cognitive biases.

We make these errors in judgment unconsciously, without recognizing them, and we will keep doing so unless we understand them and know to watch out for them.

The halo and horn effect can be seen in our everyday interactions, our friendships, and our relationships. Even our decision to be kind or dismissive of a stranger is impacted by this bias, but its implications also stretch farther.

In reality, the halo and horn effect can be extremely damaging for us and the people we interact with. Our inbuilt stereotypes compel us to judge people of a certain type more harshly than others, while also giving unfair attention and regard to those of another type.

Halo And Horn Effect In The Workplace

These effects can be seen widely in workplaces. It is also in work settings that they may be of the greatest consequence.

In interviews, people may be unfairly denied opportunities because of a negative horn created by their physical appearance, ethnicity, gender, etc. Others may be given unfair advantages because of the halos they have. Keep in mind that this is separate from and in addition to the conscious biases so often exhibited by people.

A 1979 study showed that overweight people were graded more negatively on job performance. In hiring situations, overweight applicants and those of average weight were compared. Despite demonstrating identical performance, the former were found to be less preferred.

A 1991 study showed that attractive men started with higher salaries and their earnings increased over time. The starting salaries of women were not found to be affected, but later on, they were found to earn more. A recent study showed that stuttering creates a horn effect that leads to perceptions of low self-esteem, intelligence, and motivation. These negatively impact how that person’s leadership qualities are judged.

This research is just the tip of the iceberg. Without a doubt, the halo and horn effect frequently comes into play in the workplace.

Halo And Horn Effect In Marketing

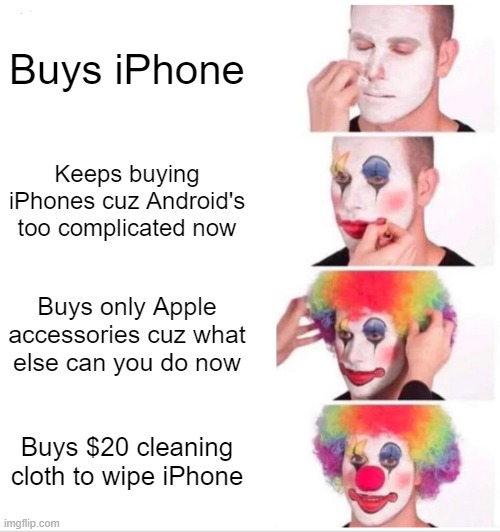

How a consumer judges a product is based on much more than the product itself. It’s also about its popularity, familiarity, and associations with other positive and negative things.

The halo effect drives the value of a ‘brand’ in marketing. Just because the brand has a history of releasing good products, you will judge new products more favorably. A prime example of this is Apple. Who else could get away with selling a 6-inch piece of cloth for $20? iPhone screens cannot be wiped with any old rag, duh.

The halo effect is also why brands choose high-profile, attractive celebrities as their brand ambassadors. Even though these celebrities typically have no qualifications to vouch for the products, and therefore should not logically impact our decision to buy the product, we still trust them. It would make more sense to have a cosmetician talk about a makeup line or an engineer talk about a new car, but we all know that wouldn’t have quite the same impact.

Showing Beyonce endorsing Pepsi says nothing about the drink. It shouldn’t make me choose, say, Pepsi over Coca-cola, but their star-studded ads make me want to drink Pepsi… and I don’t even like Pepsi!

Other Instances Of The Halo And Horn Effect

The ‘love at first sight’ trope is yet another instance of these effects. There is no logical way you can feel a deep emotion like love for a practical stranger whom you know nothing about. This might happen because of the halo effect. You find a person to be good-looking, and then your subconscious assumes that they are also kind and funny and sweet and smart, even though you have no reason to believe that.

There’s more, of course. In politics, in courts, the stock market, and countless other aspects of life, we can recognize these effects at play.

Angels And Demons

Understanding the halo and horn effect helps us to recognize, deconstruct, and overcome our cognitive biases. If we know why we make the judgments we do, we can work at not falling into the trap of split-second judgments that turn out to be horrendously misguided.

Let’s not let first impressions fool us into classifying people as angels or demons, and instead try to understand them as they are. In reality, the world is far from black and white.

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA).

- (1978) Empirical Evidence of Halo Effects in Store Image Research .... acrwebsite.org

- Inferences on Negative Labels and the Horns Effect | ACR. acrwebsite.org

- Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G., & Longo, L. C. (1991, July). What is beautiful is good, but…: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin. American Psychological Association (APA).

- Thorndike, E. L. (1920, March). A constant error in psychological ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA).