Table of Contents (click to expand)

The “tragedy of the commons” may not always be the case with resources that are neither owned by the government nor private individuals. Solutions can be as easy as developing effective communicative structures within communities for collective usage.

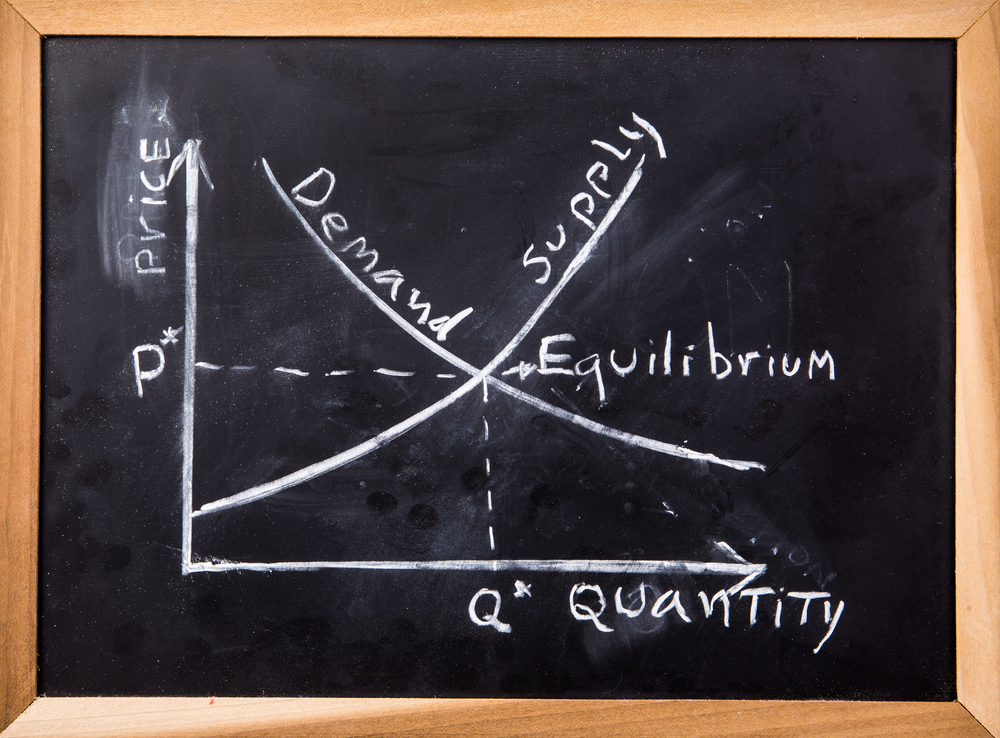

The principles of economics say that the law of supply and demand is the most efficient way to allocate resources among competing users in society. Decisions on the price and quantity of goods sold in the market are best arrived at by letting the market operate freely. A free market allows the forces of demand and supply to arrive at optimal prices and quantities. For most goods, letting demand and supply dictate prices works out.

Think about goods like education, streetlights, common grazing ground, law and order, access to drinking water and many more. The commonality among these is that, if left to the markets, these goods would not be optimally distributed.

Economists believe that the markets fail to allocate these types of goods. This is where the government steps in to provide for such goods. The government must provide access to certain goods, irrespective of the user’s financial status, as a society collectively gains from these benefits.

Public Goods Vs Common Property Resources

Law and order, defense, police, and national parks are some prime examples of public goods. The government provides these goods to the citizens via taxes. They are not treated as a market good by charging any user individually for using it.

These goods are non-excludable, meaning that, in principle, no individual can be denied using them if the government provides them. For instance, no child can be denied admission to a public school. It is freely available for all!

At the same time, using a public good doesn’t necessarily mean that less will remain for others. For instance, my visit to a public park doesn’t mean, in principle, that you cannot visit it simultaneously. The essence is that people’s consumption does not affect the supply of the good.

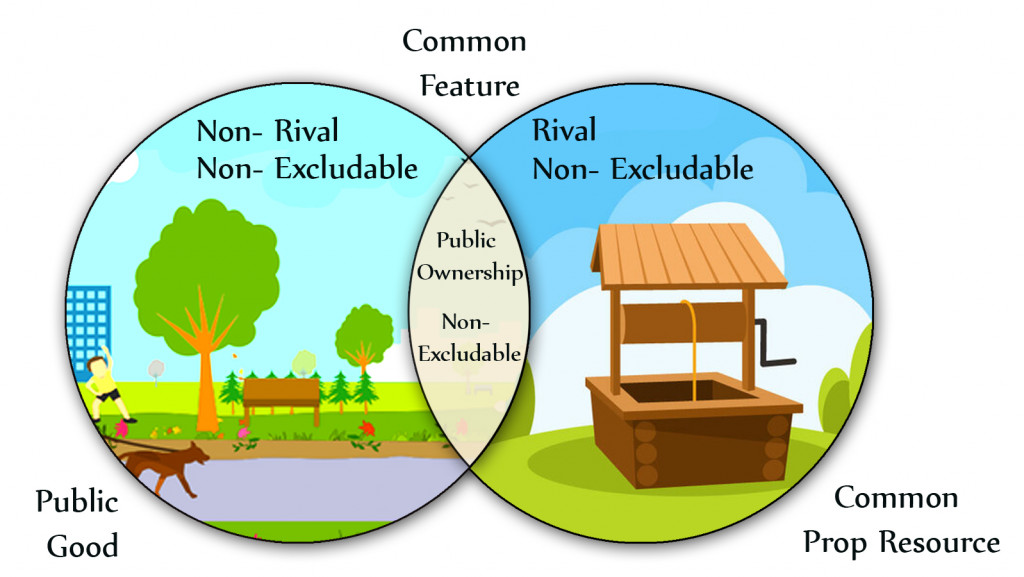

In economics, public goods are known by two standard features, i.e.; they are non-excludable and non-rivalrous.

On the other hand, think of a common grazing plot, stock of fish in an ocean, or even a tree growing in a public place that bears fruit. No individual owns these goods. Since ownership is not clearly defined, they tend to be overused. For instance, nobody stops you from fishing in the ocean or using the entire grazing area for your domestic animals. This makes the above goods non-excludable.

However, unlike public goods, one person’s decision to go overboard will affect the quantity available for others. For instance, overfishing by one fisherman would deplete the fish available for another fisherman.

To sum it up, the goods described above have two standard features, i.e., they are non-excludable, but rival. Goods exhibiting these characteristics are known as common property resources.

The tendency of public property to be constantly subjected to exploitation is known as the tragedy of the commons. Just as the phrase suggests, the depletion of resource availability for others is the sad part of such goods. In this instance, one individual usurps gains. Still, collectively, it causes harm to others due to the non-availability of that resource in sufficient quantities and even natural resource depletion, in some instances. The costs are collectively borne, but the gains are usurped by one, hence the term.

Bear in mind that the classification of resources must be done keeping the context in mind. They are not written in stone. A public good can also become a common property resource and vice-versa. For instance, if national parks get overcrowded, they no longer meet the strict definition of being non-rival and non-excludable. Now that the park is congested, the gatekeepers need to exclude people from entering the park, thus making it excludable.

Also Read: What Are Global Commons?

Is The Tragedy Of Commons A Standard Feature Of Common Property Resources?

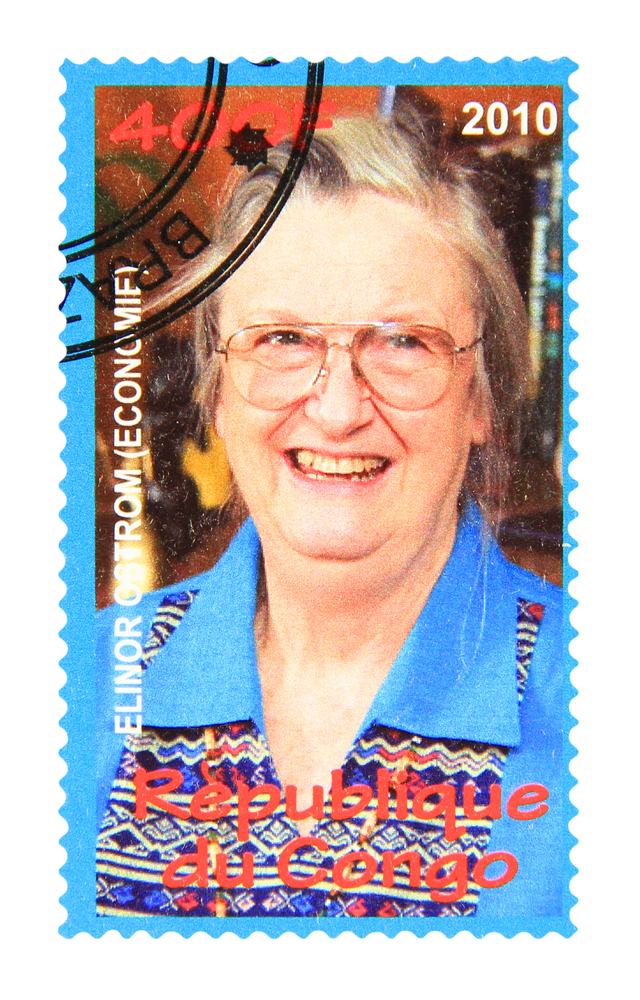

The first woman to win a Nobel Prize in 2009, Elinor Ostrom, begs to differ. During one of her field studies on irrigation systems in Nepal, she observed that users did better than the government in handling such resources.

Just because a resource is commonly owned does not mean it is always subject to over-usage and depletion. She developed the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework built on the foundation of game theory.

However, the IAD framework considers many factors before arriving at a decision. Under game theory, it is assumed that an individual is aware of each choice’s outcomes and can rationally pick what is right for the situation. It is also assumed that the individual participating in the game is able to rank his preference for each outcome.

The IAD framework looks at multiple variables, such as the interplay between the attributes of a community, the commonly agreed-upon rules in use over a common property resource, and the biophysical conditions. Here, individuals are not independently arriving at these rules, but instead through what Ostrom has coined ‘cheap talk’.

Cheap talk is how resources can be collectively optimized by communicating various strategies among users, rather than the government or intervention by any private player.

The opportunity to be able to talk to one another face to face and arrive at solutions and penalties has been shown to give positive joint returns to the entire community, while keeping governments at bay. This was observed in more than 500 case studies conducted by Ostrom and her team. Such systems are not led by one individual or any institution, but are instead polycentric, where communities collectively reflect on the status of the resource and decide on its usage patterns, and tend to be rational in their own right.

Ostrom has depicted how simplified solutions that follow the bottom-up approach helped facilitate better resource usage. She even highlights that tragedy for her, as seen in her field studies, occurred due to external intervention exerting their powers to gain a personal advantage. She was therefore a staunch proponent of community-led initiatives.

Also Read: Why Is The Problem Of Resolving Climate Change A Classic Case Of The Tragedy Of The Commons?

How well do you understand the article above!