Table of Contents (click to expand)

There are many different kinds of laughs, each in response to the situation that stimulates it. Researcher Ramon Mora-Ripoll in a study identified five different kinds of laughter, they are: genuine/spontaneous laughter, self-induced/simulated laughter, stimulated laughter (for example, tickling), induced laughter (for example, as the result of a drug), and pathological laughter.

A belly laugh is when we have a burst of loud and heavy laughter. Cackling is laughter that sounds like a hen after laying an egg, and one that a villain does! Chuckling is when we have a short and suppressed laugh, say at a mediocre joke.

We giggle when we’re nervous or when we say something foolish. Some jokes can make us howl, while sniggering is disrespectful or petty laughter. Pigeon laughter is when we laugh without opening our mouths, which triggers a “humming” noise that sounds a lot like a pigeon!

You laugh differently in different situations. This means that our brain understands the situation and helps us react in a way that is most appropriate. Whether we chuckle or giggle, our brain is doing all the work behind the scenes! This article helps uncover different kinds of laughter we have, as well as the neuroscience behind the act itself.

Kinds Of Laughs

Humor is subjective. What makes you laugh may leave me with an arched eyebrow. Moreover, humor and laughter, though used interchangeably, are different from each other.

Humor is the stimulus, the joke in this case. Laughter is the physical response or reaction.

Researcher Ramon Mora-Ripoll in a study identified five different kinds of laughter, which are: genuine/spontaneous laughter, self-induced/simulated laughter, stimulated laughter (tickling), induced laughter (drug-caused), and pathological laughter.

Before we dig into the main regions of the brain associated with humor and laughter, there is one important distinction to understand.

Even though we have listed a plethora of laugh types, there are broadly two kinds: involuntary laughter and voluntary laughter.

Involuntary laughter, also referred to as Duchenne laughter, is an emotionally-driven response.

Voluntary laughter, also known as non-Duchenne laughter, is more controlled and intentional. This is when people make jokes to warm up a crowd, or may use humor to build rapport in a social setting, and includes social smiles.

Also Read: Why Is It So Difficult To Make Someone Laugh?

Which Parts Of The Brain Are Involved In Laughter?

When scientists study laughter and what makes us laugh, they often see how different laughs stimulate the brain. They see these changes in the brain using brain imaging techniques, such as MRI and fMRI scans, to find the neurological basis of humor.

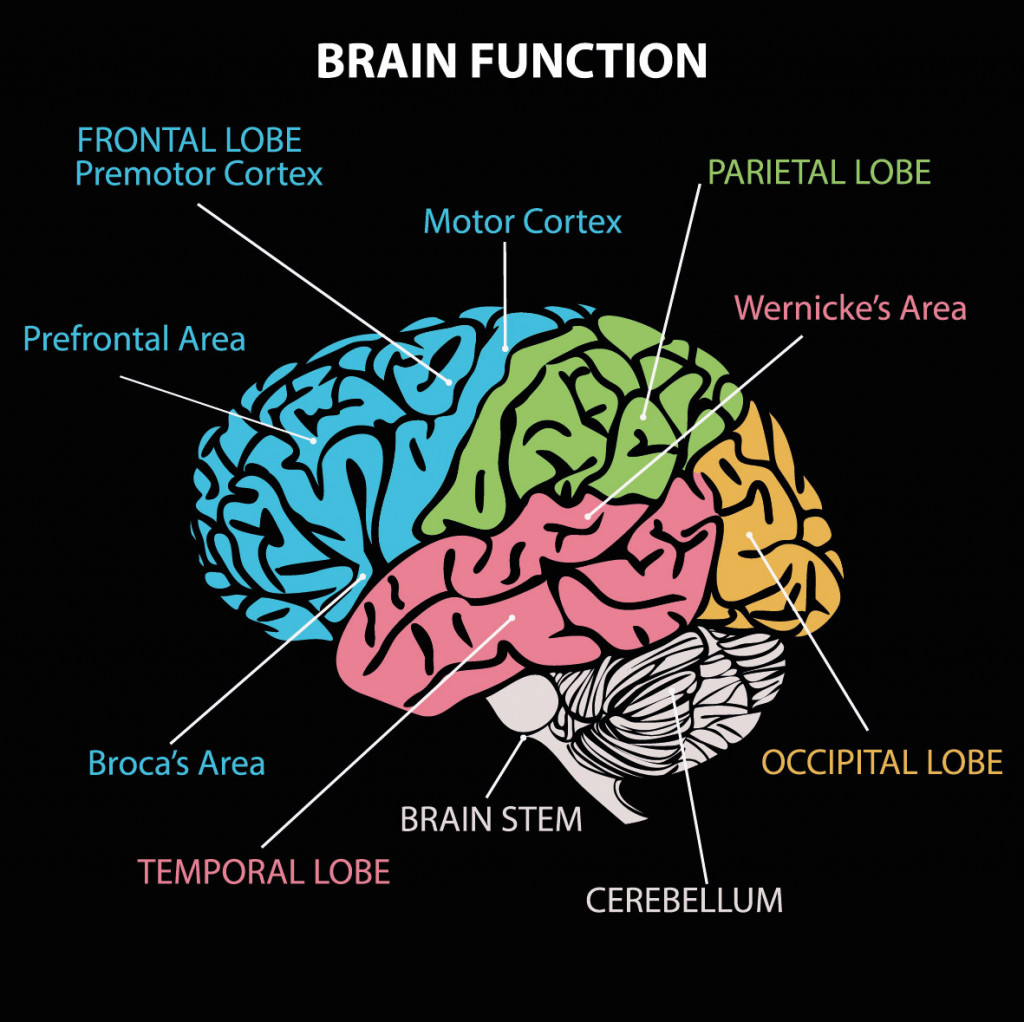

One study found that when participants read funny sentences, brain activity increases in the language centers of the brain: Broca’s area—associated with language production—and Wernicke’s area—involved in language comprehension.

This indicate that understanding humor depends on our knowledge of the language in which jokes are being made and we must be able to comprehend it.

Another study that used fMRI highlighted that participants who read puns (involving the use of their linguistic or language comprehension ability) showed activation in their left posterior middle temporal gyrus and the left inferior frontal gyrus. The left posterior middle temporal gyrus and the left inferior frontal gyrus are involved in helping us recall semantic (language) meanings.

Interestingly, when participants were asked to rate the funniness of the puns they read or heard, there was activity in their medial ventral prefrontal cortex. The activation of this brain area (prefrontal cortex) shows that we do use our cognitive (thinking) abilities and try to rate humor objectively when asked to do so.

These findings tell us that humor is not all that automatic or unconscious, as it may appear on the surface. It actually involves a lot more brain processes of language production, comprehension, thinking and reasoning, and remembering the information presented to us so that we can understand it in the context in which it is presented. That is why sometimes we don’t find jokes funny when we’re unaware of the context or the subject matter to which the jokes are related!

In the brain, there are two pathways of laughter, one for involuntary laughter and one for voluntary laughter.

Also Read: The Science Of Laughter: Why Do We Laugh?

Involuntary Laughter In The Brain

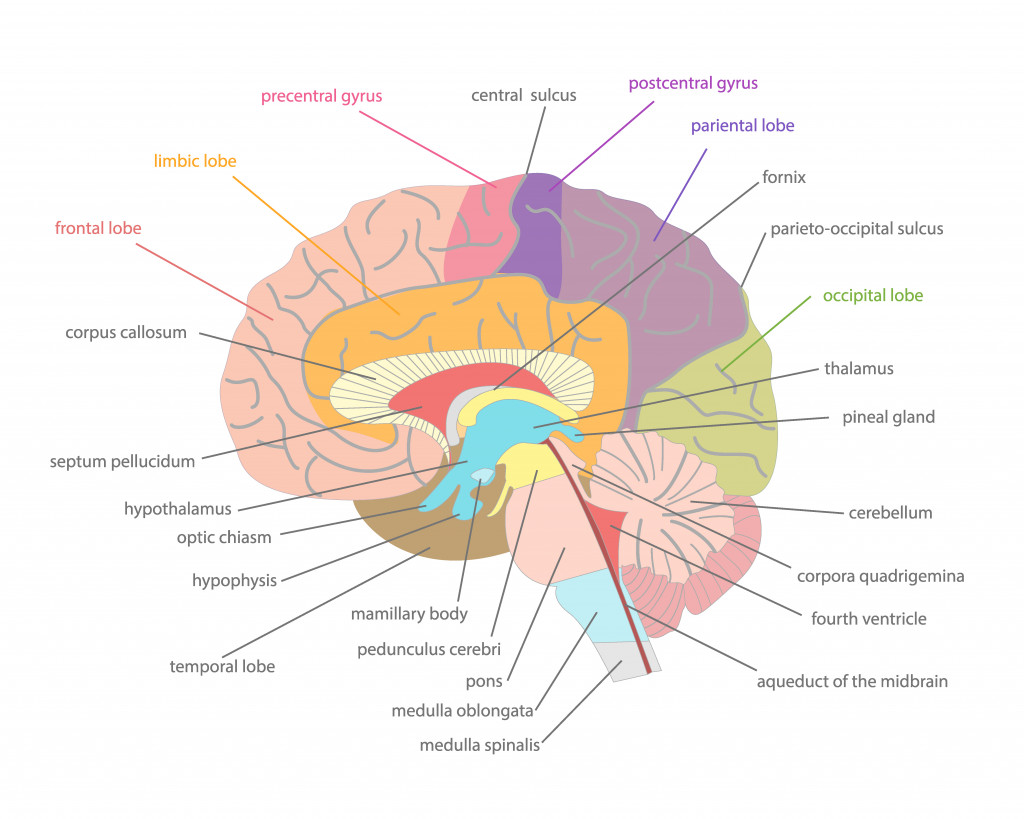

Involuntary laughter evokes a response and activity in the amygdala, thalamic regions of the brain, and the brainstem. These brain areas are also responsible for processing emotions.

Voluntary Laughter In The Brain

Voluntary laughter begins in the premotor opercular area of the temporal lobe and then moves down to the motor cortex and pyramidal tract before finally moving to the brainstem. This is because voluntary laughter involves more than just an emotional response; it also involves our reasoning and thinking processes to be active.

Studies that used fMRI and PET scans show which parts of the brain were active when participants experienced humor.

In summary, we know that there are different kinds of laughter and that laughter is associated with various areas of the brain. However, there are still many missing clues when it comes to research on laughter. For instance, researchers have yet to discover why people find different kinds of jokes funny and why exactly humor is subjective. Researchers also have yet to come up with an objective and scientific method to measure laughter in quantitative or neurological units. Every day we are approaching more insights on humor, but it’s fair to say that we still have a lot of punch lines to uncover!

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- (2010) The therapeutic value of laughter in medicine - PubMed. United States National Library of Medicine

- (PDF) Freud's theory of humor. - ResearchGate. ResearchGate

- (2012) Studies in Literature and Language - CSCanada. This result comes from www.flr-journal.org

- Chapman A. J.,& Foot H. C. (2013). It's a Funny Thing, Humour: Proceedings of The International Conference on Humour and Laughter 1976. Elsevier

- Voluntary and involuntary laughter in the brain - ResearchGate. ResearchGate

- The effects of listening comprehension of various genres of ... : NeuroReport - journals.lww.com

- Goel, V., & Dolan, R. J. (2001, March). The functional anatomy of humor: segregating cognitive and affective components. Nature Neuroscience. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Gervais, M., & Wilson, D. S. (2005, December). The Evolution And Functions Of Laughter And Humor: A Synthetic Approach. The Quarterly Review of Biology. University of Chicago Press.

- (2014) The social life of laughter - ScienceDirect.com. ScienceDirect

- Sumners, A. D. (1988, January). Humor: Coping in Recovery from Addiction. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. Informa UK Limited.

- Anderson, C. A., & Arnoult, L. H. (1989, June 1). An Examination of Perceived Control, Humor, Irrational Beliefs, and Positive Stress as Moderators of the Relation Between Negative Stress and Health. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. Informa UK Limited.

- Moran, C. C., & Massam, M. M. (1999, January). Differential Influences of Coping Humor and Humor Bias on Mood. Behavioral Medicine. Informa UK Limited.

- Kelley, M. L., Jarvie, G. J., Middlebrook, J. L., McNeer, M. F., & Drabman, R. S. (1984). Decreasing burned children's pain behavior: impacting the trauma of hydrotherapy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. Wiley.

- Ventis, W. L., & Ventis, D. G. (1989, March 16). Chapter 9: Guidelines for Using Humor in Therapy with Children and Young Adolescents. Journal of Children in Contemporary Society. The Haworth Press.

- Scott, E. M. (1989, June 21). Humor and the Alcoholic Patient:. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. Informa UK Limited.