Table of Contents (click to expand)

A phantom limb sensation is a sensation that feels as though it is coming from the lost limb of amputees. Amputees may feel a pain, an itch, or any other sensation in the non-existent limb, as if it is still present and attached.

You’ve surely heard of the phantom that terrorizes the residents of the Opera house, but have you heard of phantoms in the brain that torture amputees?

What Is A Phantom Limb?

Some sensations that we feel can be “phantoms” in the sense that they may be illusory or not real.

We often feel phone vibrations when our smartphone is not actually ringing. Similarly, a phantom limb sensation is a sensation that feels as though it is coming from the lost limb of amputees. They may feel a pain, an itch, or some other sensation in the non-existent limb, as if it was still attached. This is called a “phantom” or “ghost” limb.

The syndrome was first described in detail by an American neurologist, Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, in 1829. Several older theories failed to explain how and why this phenomenon occurs, and only recently have we come close to identifying the truth behind this bizarre syndrome.

A deep study of the why and how of this syndrome helped scientists understand the quirky nature of our brains. To fully grasp the nature of this illusion, we must understand how our brain manages sensations from each of our body parts.

Also Read: Do We Feel Pain When We’re Unconscious?

Maps In The Human Brain

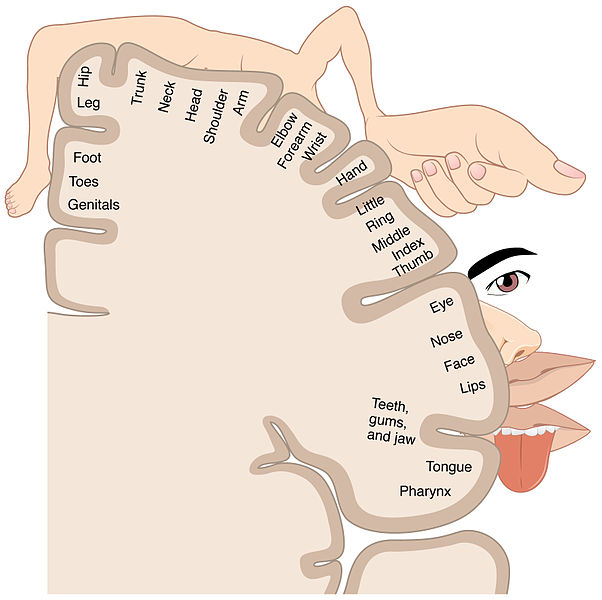

The sensory and motor regions of the human brain take care of perceiving sensations and moving body parts, respectively. Both of these regions in the brain contain a map of our body called “somatotopic” maps.

For example, while one region in the map is dedicated to the right forearm, another region is responsible for the right wrist, and so on. This map is arranged in the same way in all human brains.

Dr. Wilder Penfield, a neuroscientist, discovered these elaborate maps through a series of cutting-edge experiments. He stimulated specific brain regions of patients using electricity during surgery and observed the reactions and results. When he stimulated a particular part of the sensory region, patients reported sensations in a specific body part, as if it was being touched.

This made him realize that sensations from each body part are processed by distinct brain regions. He discovered the entire “somatotopic” map in the brain through this method.

Also, sensitive regions on the body were found to be represented by larger regions in the brain. For example, a larger region was found to be devoted to the fingers than the arm. This is why we can easily tell two close points of touch apart on our fingers, as compared to detecting the same stimulus on our arms!

What Causes Phantom Limb Sensation?

When we are touched on the arm, the nerve endings carry the signals of “being touched” to the sensory region of the brain, which is what gives us the feeling of being touched.

The sensory area of the brain receives these signals from every part of the body.

When a person loses a limb, they also lose all input from that limb to the brain. However, the brain still retains the ‘mini’ map for the lost limb. A right arm amputee’s brain will still carry neurons in the sensory region for that missing right arm.

Any activity in this retained brain region would have originally come from an intact right arm. However, after amputation, any activity happening in this brain region can make the amputee feel as though the sensation is coming from the non-existent arm.

So… how does activity arise in the sensory region of a lost limb?

Our brain has an exceptional ability to change itself, an ability called “neuroplasticity”. After losing a limb, the brain region corresponding to that lost limb, in some ways, becomes unused. Such unused regions are then recruited to take care of functions of the body part lying near it on the cortical map.

For example, the “hand” area lies next to the “face” area in the sensory cortex of the brain. Therefore, after the loss of an arm, the neurons from the hand area get recruited to the face area.

Initially, after amputation, this mix-up causes the brain to think that sensations from the face are coming from the lost hand. Due to this, many amputees report that touching their face gives them sensations from a “phantom” arm, as if the lost limb were still there!

Thus, the culprit for these phantom pains is the ever-changing brain maps that confuse our sensations.

Also Read: Why Does A Heart Attack Or Angina Manifest As Pain In The Left Arm Or Chest?

Phantom Limb Pain

Some amputees feel pain and discomfort stemming from their lost limb, a condition called phantom limb pain, but how can you treat pain in a non-existent limb?

This problem required clinicians to come up with novel ideas to relieve such enigmatic pain. One such method was using a mirror. A mirror is placed vertically between the torso and the lost limb, which would create a reflection of the intact limb to make it look like the lost limb. Patients reporting pain in the “phantom” limb can use the mirror to look at the reflection of the intact limb and move it as necessary to relieve pain.

Gradually, the sensory region for the lost limb gets mapped to new body parts. After this point, phantom limb pain can be relieved by treating pain from the newly assigned body part. For example, stroking the face may relieve phantom arm pain in a patient because the sensory region for the arm now handles sensations from the face.

Conclusion

Phantom sensations are unique phenomena that arise due to the “neuroplasticity” of the brain. Recycling the sensory region of a lost limb through neuroplasticity in the brain creates the illusion in amputees that sensation is coming from the lost, “phantom” limb.

Plainly put, this happens due to a simple mix-up in the brain’s wiring. This phenomenon is proof that the brain is capable of constant modification based on new inputs.

Neuroplasticity can give us problematic “phantoms”, but also help us seamlessly incorporate new skills into our repository. A study on taxi drivers showed that their intense training on routes and maps increased brain tissue in regions that handle navigation. Phantom or not, evidence like this is encouraging, since it demonstrates that our brains are capable of large changes even at ages well past our brain’s “formative” years.

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- Nathanson, M. (1988, March 1). Phantom limbs as reported by S. Weir Mitchell. Neurology. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health).

- PENFIELD, W., & BOLDREY, E. (1937). Somatic Motor And Sensory Representation In The Cerebral Cortex Of Man As Studied By Electrical Stimulation. Brain. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- (1996, April 22). Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- Ramachandran, V. S., & Rogers-Ramachandran, D. (2000, March 1). Phantom Limbs and Neural Plasticity. Archives of Neurology. American Medical Association (AMA).

- Maguire, E. A., Gadian, D. G., Johnsrude, I. S., Good, C. D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S. J., & Frith, C. D. (2000, March 14). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- (1992) Phantom Limbs - jstor. JSTOR