Table of Contents (click to expand)

Migratory birds can fly for 8,000 km or more without stopping to eat. These birds beef up before their flight, and also depend on fats for their energy requirements, since fats are more efficient than carbohydrates at releasing energy.

Most of us can’t walk more than 5 km at a time. We look at endurance runners who jog 25 km in one single stretch with awe. Can any of us imagine walking 30,000+ km every year?

Arctic terns do just that!

Technically, they don’t walk… they fly.

Fondly called, “The champions of migration” these medium-sized birds that weigh in at just over 100 g migrate pole to pole every single year.

They’re monogamous birds that breed in the Northern hemisphere in the Arctic summer. Then, when winter arrives at the North Pole, they migrate to the south. They travel in flocks to the South Pole and set up camp for Southern Summer. These birds chase sunlight in the most extreme sense of the word!

As if this wasn’t cool enough, this trip includes an 8,000 km non-stop flight over the Indian Ocean!

That’s a bit longer than your average marathon.

So, how do birds make these amazing trips? Do they ever run out of fuel and get tired?

Where Do Birds Get Their Energy?

Most animals primarily break down various carbohydrates—glucose being a key sugar—to meet their energy needs. Birds shake things up a bit and instead choose to break down fats.

Fat or lipid metabolism is a series of biological processes that metabolize and derive energy from fats (i.e., fatty acids). Studies have revealed that birds use fatty acids as their energy source.

So what makes fats such an excellent fuel for birds, especially those that take on long and arduous migrations?

Also Read: How Do Birds Break Down Their Food If They Don’t Have Any Teeth?

Fats Are Easier To Store

Migratory birds have been known to “beef up” before long-distance flights. They shift to a fat-rich diet. Birds overeat (hyperphagia) before embarking on a long migration. In fact, many warblers have been known to put on up to twice their body weight before embarking on a migration.

This hyperphagia alone does not account for their rapid fattening. Birds also get more efficient at assimilating nutrients from their food.

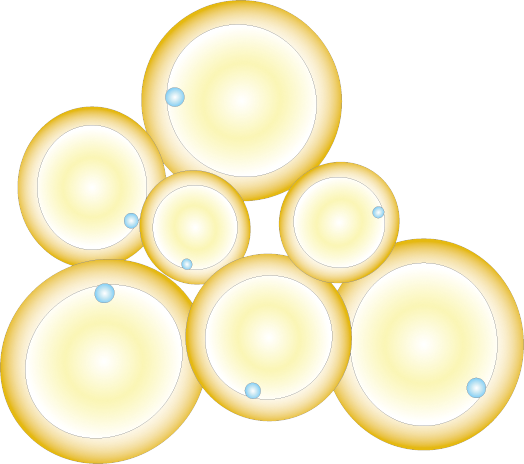

Birds are so specialized to store fat that most migratory birds can store up to 50–60% of their body mass as fats. They do this by keeping fats in cells known as adipocytes, or fat cells. These adipocytes are right under the skin in extra-muscular tissues. Avian adipocytes can store up to 95% of their volume as fatty acids. They can also store fats in their extra-muscular tissues and in their liver (similar to glycogen storage).

Researchers monitored the levels of free fatty acids in three species of small songbirds (passerines). They found elevated levels of free fatty acids and glycerols in those birds on nocturnal migratory flights, as compared to resting birds. This means that migratory birds have developed unique pathways to increase their fatty acid storage capacity.

One suggestion points to the levels of very low-density lipoproteins or VLDLs. They are a type of cholesterol that help increase the efficiency of fatty acid transport through the bloodstream to the muscles. They streamline fatty acids delivery to flight muscles (for example, the pectoralis muscles).

Birds can store fatty acids in the liver, which are then converted to triglycerides. These triglycerides are transported out of the liver as VLDLs. They reach flight muscles and are converted there back into fatty acids. The enzyme lipase, produced by the endothelial cells of the flight muscles, mediates this reaction.

Migratory birds have high levels of VLDLs in their bloodstream, as compared to other animals that take on similar long-endurance exercise.

In the flight muscles, fatty acids finally undergo oxidation to generate energy.

Also Read: Why Are Fats The Preferred Energy Storage Molecule?

Fat Is More Efficient Than Carbohydrates

A little fat goes a long way, at least when it comes to deriving energy from it.

One gram of fat produces around 9 kilocalories of energy. This is significantly better than carbohydrates, which only provide 4 kilocalories of energy per gram.

How Do Birds Use This Energy?

Birds migrate long distances just like elite athletes run marathons. They choose stamina over speed. In fact, they minimize energy use anywhere they can.

Many birds take off by rapidly beating their wings. This makes take-off the most energy-intensive step in their flight. The take-off is anaerobic and birds use stored glycogen (a carbohydrate) to launch.

However, during long-distance flights, birds don’t beat their wings much at all.

Grey-headed albatross are seabirds that migrate across Southern seas between breeding seasons. They very rarely beat their wings. In fact, they cover most of this journey by just gliding and soaring. Instead of flying in energy-expensive bursts, they glide and soar on thermals, taking advantage of the winds through which they fly!

Also Read: How Do Birds Conserve Energy During Flight?

How well do you understand the article above!

References (click to expand)

- McWilliams, S. R., Guglielmo, C., Pierce, B., & Klaassen, M. (2004, September). Flying, fasting, and feeding in birds during migration: a nutritional and physiological ecology perspective. Journal of Avian Biology. Wiley.

- Becciu, P., Panuccio, M., Dell’Omo, G., & Sapir, N. (2021). Groping in the fog: soaring migrants exhibit wider scatter in flight directions and respond differently to wind under low visibility conditions. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 745002.

- Butler, P. J. (2016, September 26). The physiological basis of bird flight. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- Harrison, J. (2019, September 3). The highs and lows of bird flight. eLife. eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd.